| 141

7. The Khazar Rovas

7.1. Description of the script

7.1.1. General properties

The Khazar Rovas (KR) script is directed exclusively from right to left; there is no casing and no numerals in any of the known

Khazar Rovas relics. In some cases, borrowing characters from other scripts led to the multiplication

(duplication) of KR characters (Sec. 3.5.2). Sporadically and not consequently, KR applied vowel harmony in case of some consonants

(front consonats used with front vovels, back consonats used with back

vovels, i.e ki vs. ɣï (ɣı), qï (qı)).

7.1.2. Khazar Rovas characters

Table 7.1.2-1 details the character repertoire of KR. The number of occurrences of each glyph in each relic is given in brackets at the end of the rows. In the first column the glyphs of the normalized

Khazar Rovas characters are listed according to the international standard proposal of the Hungarian Standards Institution.468

The notations like the following “in As-Alan, in

lig.,

sound: /a/ (4)” must be viewed critically, for example:

1. As-Alan attribution is frivolous, unjustified, of notional character. Genetic analysis of similar

claims demonstrated no connection between imagined “As-Alan” and people buried.

2. The presumption of widespread ligatures in reality stands for “we do not know”

3. Accordingly, the phonetic value may be incorrect

4. The phonetic value must be consistent with the morphology of the script

5. Attribution to “As-Alan” is unprovable because there are no known examples of “As-Alan” language

in space and time.

Ditto with attributions Khazar, Kipchak, Ogur, etc. Ditto with dating, none of which is

instrumental and all of which are of notional character. In the sources, all attributions and datings

are preceded by qualifiers like “probably”, “possibly”, “likely”, and such, and those that are not

qualified deserve even less credibility. The proposed reading is erroneous if a scholar needs a

ligature for the reading, unless a bi-lingual inscription dictates a suspicion of a ligature. |

Table 7.1.2-1: KR characters and examples of each glyph in relics

| Glyph |

Name |

IPA symbol |

Examples of the Khazar Rovas glyph in relics |

| Y |

FORKED

A |

/a/ɛ/ |

Village

Krivy.,

Sec.

7.2.7, in

As-Alan, in

lig.,

sound: /a/ (4)

Ermen Tolga, Sec. 7.2.12, in Khazar, sound: /a/ɛ/ (6)

Mayak Large, Sec. 7.2.9, in Khazar, in lig.,

sound: /a/ (3) sound: /a/ (3)

Mayak Smaller inscriptions, 9th c., Fig. 7.2.10-1,5a, in Khazar, partly in ligature, sound: /a/ (2)

Mayak Smaller, 9th c.,

Fig. 7.2.10-3, in As-Alan, in ligature, sound: /a/ (1) |

| X |

B |

/b/ |

Homokmegy-Halom, 10th c., Sec. 7.2.13, in Turkic (1)

Mayak Smaller Inscr., 9th c., Fig. 7.2.10-2, in Ogur (1) |

|

ANGLED B |

/b/ |

Jitkov, first third of 8th c., Sec. 7.2.1, in Khazar (3)

Achiktash, first half of the 8th c., Sec. 7.2.4, in Kypchak (2)

Khumara, 9th—10th c., Fig. 7.2.5-3, in Khazar (1)

Novocherkassk, 9th—10th c., Sec. 7.2.6, in Kypchak (1)

Village Krivyanskoe, 9th— 10th c., Sec. 7.2.7, in As-Alan (1)

Ermen Tolga, 8th—10th c., Sec. 7.2.12, in Khazar (8)

Mayak Smaller, 9th c„ Fig. 7.2.10-1,5a,b, in Khazar (2)

Bilyar, 11th- 13th c., Sec. 7.2.16, in Ogur (l) |

|

ARCHED B |

/b/p/ |

Jitkov, Bow Cover, 8th c., Sec. 7.2.1, in Khazar, sound: /b/ (1)

Mayak Large, 9th c., Sec. 7.2.9, in Khazar, sound: /p/ (1) |

|

RAISED B |

/b/ |

Khumara, 9th—10th c., Fig. 7.2.5-4, in Ogur (1)

Alsoszentmihâlyfalva, 920-952 AD, Sec. 7.2.14, in Khazar (1)

Mayak Large Inscr., 9th c., Sec. 7.2.9, in Khazar (4)

Mayak Smaller, 9th c., Fig. 7.2.10-3, in As-Alan, in lig. (1) |

|

TRIPLE CS (SH/S) |

/tʃ/s/ |

Achiktash, first half of the 8th c., Sec. 7.2.4, in Kypchak (4)

Khumara, 9th—10th c., Fig. 7.2.5-4, in Ogur, in ligature (1)

Village Krivyanskoe, 9th -10th c., Sec. 7.2.7, in As-Alan (3)

Mayak Large, 9th c., Sec. 7.2.9, glyph:

,

in Khazar (1) ,

in Khazar (1) |

|

ARCHED D |

/d/di/dɛ/j/dʒ/ |

Jitkov, first third of 8th c., Sec. 7.2.1, in Khazar (2)

Achiktash, first half of the 8th c., Sec. 7.2.4, in Kypchak (1)

Khumara, 9th-10th c., Fig. 7.2.5-lb,2b, in Khazar (3)

Khumara, Fig. 7.2.5-4, in Ogur, sound: /di/, in lig. (1)

Novocherkassk, 9th-10th c., Sec. 7.2.6, in Kypchak (1)

Village Krivyanskoe, Sec. 7.2.7, in As-Alan, in lig. (2)

Alsöszentmihâlyfalva, 10th c., Sec. 7.2.14, in Khazar, sound: /ed/, in ligature (1)

Ermen Tolga, Sec. 7.2.12, in Khazar, partly in ligature (6)

Mayak Large, 9th c., Sec. 7.2.9, in Khazar, partly in lig. (8)

Mayak Smaller, Fig. 7.2.10-1, in Khazar, in ligature (1)

Mayak Smaller inscr., 9th c., Fig. 7.2.10-3, in As-Alan (1) |

|

FORKED D |

/d/ |

Homokmegy-Halom, 10th c., Sec.

7.2.13, in Turkic (1) |

|

SHARP D |

/d/ð/dʒ/

(There is a large semantical difference between /d/ and /ð/, in English /ð/ is transmitted as th,

which comes in voiced and unvoiced veriety. The Türkic /ð/ is transcribed as d or δ, apparently

depicting only a voiced version. In the early Horesmian Türkic alphabet the interdental th /ð/ was

depicted as

, identical to the Futhark Þþ, which stands for voiced and unvoiced th.

This cardinally changes transcription: Ishad becomes Ishath)

, identical to the Futhark Þþ, which stands for voiced and unvoiced th.

This cardinally changes transcription: Ishad becomes Ishath) |

Jitkov, first third of 8th c., Sec. 7.2.1, in Khazar (3))

Achiktash, first half of the 8th c., Sec. 7.2.4, in Kypchak (7)

Mayaki Amphora, c., Sec. 7.2.2, in Ogur (1)

Devitsa Coins, 8lh-9th c., Sec. 7.2.3, in Khazar, in ligature (2)

Khumara, ca. 9th— 10lh c., Fig. 7.2.5-lb,2b,3, in Khazar (5)

Khumara, 9th—10lh c., Fig. 7.2.5-4, in Ogur (1)

Novocherkassk, 9th—10th c., Sec. 7.2.6, in Kypchak (3)

Village Krivyanskoe, 9th—10th c., Sec. 7.2.7, in As-Alan (3)

Minusinsk, 8th-9th c., Sec. 7.2.8, in Turkic (1)

Bilingual Khazar Coin, Sec. 7.2.11, in Khazar, in ligature (1)

Ermen Tolga, 8th—10th c., Sec. 7.2.12, in Khazar (1)

Mayak Large Inscr., 9th c., Sec. 7.2.9, in Khazar (6)

Mayak Smaller, 9th c., Fig. 7.2.10-1, in Khazar (1)

Mayak Smaller, Fig. 7.2.10-2, sound: /dʒ/, in Ogur (1)

Kievan Letter, 955-961, Sec. 7.2.15, in Khazar (1)

Bilyar, 11th-13th c.,Sec. 7.2.16, in Ogur (l) |

|

DIAGONAL E |

/ɛ/ |

Mayaki Amphora, 8th-9th c., Sec. 7.2.2, in Ogur (1)

Khumara, 9th -10th c., Fig. 7.2.5-2b,3, in Khazar, glyph:

(2)

(2)

Mayak Large, 9th c., Sec. 7.2.9, in Khazar, glyph:

(2)

(2) |

|

ANGLED E |

/ɛ/ |

Achiktash, first half of the 8,h c., Sec. 7.2.4, in Kypchak (2) |

|

ARCHED E |

/a/a:/ɛ/ |

Jitkov, 8th c., Sec. 7.2.1, in Khazar, glyph:

,

sound: /a/a:/ɛ/ (5) ,

sound: /a/a:/ɛ/ (5)

Khumara, Fig. 7.2.5-1b, 2b, 3, in Khazar, sound: /a/ (5) |

|

FORKED E |

/a/ɛ/ |

Novocherkassk, Sec. 7.2.6, in Kypchak, sound: /a/ɛ/ (3)

Alsöszentmihâlyfalva, Sec. 7.2.14, in Khazar, sound: /a/ (1) |

|

CLOSE E |

/e/ |

Achiktash, first half of the 8lh c., Sec. 7.2.4, in Kypchak (1) |

|

CENTRAL F |

/f/ |

Village Krivyanskoe, 9th— 10th c., Sec. 7.2.7, in As-Alan (1) |

|

CLOSE G |

/g/ɣ/ |

Achiktash, 8th c., Sec. 7.2.4, in Kypchak, sound: /g/ (1)

Khumara, 9,h—10th c., Fig. 7.2.5-1b, 2b in Khazar, sound: /g/ (3)

Minusinsk, 8th-9th c., Sec. 7.2.8, in Turkic, sound: /g/ (3)

Homokmegy-Halom, Sec. 7.2.13, in Turkic, sound: /ɣ/ (1)

Ermen Tolga, 8th—10th c., Sec. 7.2.12, in Khazar, sound: /g/ (1)

Mayak Large, 9th c., Sec. 7.2.9, in Khazar, sound: /g/ (6) |

|

FORKED G |

/g/ |

Khumara, 9th— 10th c., Fig. 7.2.5-4, in Ogur (1) |

| N |

GH |

/ɣ/

in As-Alan languages: /g/ |

Jitkov, 8th c., Sec. 7.2.1, in Khazar:

, sound: /ɣ/ (3) , sound: /ɣ/ (3)

Achiktash, Sec. 7.2.4, in Kypchak, glyph:

, sound:

/ɣ/ (1) , sound:

/ɣ/ (1)

Mayaki, Sec. 7.2.2, in Ogur, calligr., mirrored

, sound:

/ɣ/ (1) , sound:

/ɣ/ (1)

Khumara, 9th— 10th c., Fig. 7.2.5-2b,3, in Khazar, mirrored:

, sound:

/ɣ/ (3) , sound:

/ɣ/ (3)

Khumara, Fig.

7.2.5-4, in Ogur, mirrored:

, sound:

/ɣ/ (1) , sound:

/ɣ/ (1)

Village Krivyanskoe, Sec. 7.2.7, in As-Alan, mirrored:

, sound:

/g/ (1) , sound:

/g/ (1)

Minusinsk, Sec. 7.2.8, in Turkic, mirrored:

, sound:

/ɣ/ (1) , sound:

/ɣ/ (1)

Alsöszentmihâlyfalva, 10th c., Sec. 7.2.14, in Khazar, in ligature, sound: /ɣ/ (1)

Mayak Large, 9th c„ Sec. 7.2.9, in Khazar, sound: /ɣ/ (2)

Kievan Letter, 955-961, Sec. 7.2.15, in Khazar, sound: /ɣ/ (1) |

|

TRIPLE GH |

/ɣ/ |

Minusinsk, 8th-9lh c., Sec. 7.2.8, in Turkic, overwritten (2)

Homokmegy-Halom, 10th c., Sec.

7.2.13, in Turkic (2) |

|

ANGLED CH (KH) |

/x/ |

Mayaki Amphora, c., Sec. 7.2.2, in Ogur (1) |

|

ARCHED CH (KH) |

/x/ |

Village Krivyanskoe, 9th-10th c., Sec. 7.2.7, in As-Alan (1) |

|

FORKED CH (KH) |

/x/ |

Jitkov, Bow Cover, 8lh c., Sec. 7.2.1, in Khazar, glyph:

(1) (1)

Mayak Large Inscr., 9th c., Sec. 7.2.9, in Khazar (1) |

|

SHARP CH (KH) |

/h/ |

Achiktash, 8th c., Sec. 7.2.4, in Kypchak, sound: /h/ (4) |

|

ANGLED I |

/i/, in

ligature also /e/ |

Jitkov, Sec. 7.2.1, in Khazar, mirrored glyph (1)

Mayaki Amphora, 8lh-9th c., Sec. 7.2.2, in Ogur (1)

Khumara, 911—10th c., Fig. 7.2.5-4, in Ogur, in lig., mirrored (1)

Mayak Large, Sec. 7.2.9, in Khazar, in lig., sound: /e/ (1)

Mayak Smaller, Fig. 7.2.10-4, in As-Alan, in lig. (1)

Ermen Tolga, Sec. 7.2.12, in Khazar, in ligature, sound: /e/ (3)

Alsöszentmihâlyfalva, 10th c., Sec. 7.2.14, in Khazar, in ligature, sound: /e/ (3)

Kievan Letter, Sec. 7.2.15, in Khazar in lig., mirrored (2) |

|

ARCHED I |

/i/ï/ |

Achiktash, first half of the 8th c., Sec. 7.2.4, in Kypchak (4)

Khumara, Fig. 7.2.5-2b, 3, in Khazar, partly in ligature, (2)

Village Krivyanskoe, 9lh— 10th c.,

Sec. 7.2.7, in As-Alan (2)

Mayak Large Inscr., 9th c„ Sec. 7.2.9, in Khazar (4)

Mayak Smaller, Fig. 7.2.10-2, in Ogur, mirrored:

(1) (1)

Mayak Smaller. Fig. 7.2.10-5a,b, in Khazar, glyph:

(1) (1) |

|

CIRCLE ENDED I |

/i/ï/ |

Khumara, 9th— 10th c., Fig. 7.2.5-lb, in Khazar, glyph:

(1) (1)

Khumara, 9th— 10th c., Fig. 7.2.5-4, in Ogur (1)

Minusinsk, 8th-9,h c., Sec. 7.2.8, in Turkic, glyph:

(2) (2)

Ermen Tolga, 8th— 10th c., Sec. 7.2.12, in Khazar (1) |

|

CLOSE J |

/j/ |

Jitkov, First third of 8th c., Sec. 7.2.1, in Khazar (1)

Achiktash, first half of the 8th c., Sec. 7.2.4, in Kypchak (1)

Khumara, 9th-10th c., Fig. 7.2.5-2b,3, in Khazar, glyph: 0

(2)

Alsöszentmihâlyfalva, 920-952, Sec. 7.2.14, in Khazar (2)

Minusinsk, 8lh-9lh c., Sec. 7.2.8, in Turkic (2)

Mayak Smaller, 9th c., Fig. 7.2.10-1, in Khazar (1)

Mayak Smaller, 9th c., Fig. 7.2.10-4, in As-Alan, in lig. (1) |

|

FORKED K |

/k/ |

Jitkov, first third of 8th c., Sec. 7.2.1, in Khazar, in ligature (1)

Bilingual Khazar Coin, Sec. 7.2.11,

, in Khazar (1) , in Khazar (1)

Mayak Smaller, 9th c., Fig. 7.2.10-4, in As-Alan (1)

Kievan Letter, 955-961, Sec. 7.2.15, in Khazar (1) |

|

KUE |

/ky/ |

Alsöszentmihâlyfalva, 920-952, Sec. 7.2.14, in Khazar (1) |

|

ARCHED L |

/l/ |

Khumara, 9th- 10th c., Fig. 7.2.5-4, in Ogur (1) |

|

CROSSED L |

/l/ |

Homokmegy-Halom, 10th c., Sec. 7.2.13, in Turkic (1) |

|

FORKED L |

/l/ |

Minusinsk, 8lh-9th c., Sec. 7.2.8, in Turkic (1) |

|

SIMPLE L |

/l/ |

Achiktash, first half of the 8th c., Sec. 7.2.4, in Kypchak (1)

Mayak Large inscr., 9th c., Sec. 7.2.9, in Khazar (2)

Alsöszentmihâlyfalva, Sec. 7.2.14, in Khazar, in lig. (1)

Kievan letter, 955-961, Sec. 7.2.15, in Khazar in lig.(1) |

|

LT |

/lt/ |

Mayak Large inscr., 9th c., Sec. 7.2.9, in Khazar (2) |

|

OPEN M |

/m/ |

Achiktash, first half of the 8th c., Sec. 7.2.4, in Kypchak (2)

Mayaki Amphora, 8th-9lh c., Sec. 7.2.2, in Ogur (1)

Khumara, 9 — 10,h c., Fig. 7.2.5-2b,3, in Khazar (4)

Minusinsk, 8th-9th c., Sec. 7.2.8, in Turkic (2)

Bilingual Khazar Coin, Sec. 7.2.11, in Khazar (1)

Ermen Tolga, 8th— 10th c., Sec. 7.2.12, in Khazar, mirrored:

(4) (4)

Mayak Large Inscr., 9th c., Sec. 7.2.9, in Khazar (2)

Mayak Smaller Inscr., 9th c., Fig. 7.2.10-2,, in Ogur, mirrored:

(1) (1)

Mayak Smaller, Fig. 7.2.10-4, in As-Alan, mirrored:

(2) (2) |

|

ROUND M |

/m/ |

Novocherkassk, 9th— 10th c., Sec. 7.2.6, in Kypchak (2) |

|

N |

/n/ |

Jitkov, first third of 8th c., Sec. 7.2.1, in Khazar (1)

Khumara, 9,h-10th c„ Fig. 7.2.5-2b, 3, in Khazar (3)

Homokmegy-Halom, 10th c., Sec. 7.2.13, in Turkic (2)

Mayak Large, 9th c., Sec. 7.2.9, in Khazar, partly, in lig. (5)

Mayak Smaller, 9lh c., Fig. 7.2.10-3, in As-Alan, in lig. (1)

Bilyar, 1 l,h-13th c„ Sec. 7.2.16, in Ogur(l) |

|

ANGLED N |

/n/ |

Khumara, Fig. 7.2.5-lb,2b,3, in Khazar, glyph:

(5)

(5)

Mayak Large Inscr., 9th c., Sec. 7.2.9, in Khazar (2) |

|

FORKED N |

/n/ |

Achiktash, Sec. 7.2.4, in Kypchak, glyph:

(2) (2)

Mayaki Amphora, 8th-9th c., Sec. 7.2.2, in Ogur, glyph:

(4)

(4)

Khumara, 9th— 10th c., Fig. 7.2.5-3, in Khazar, glyph:

(1)

(1)

Novocherkassk, 9th—10th c., Sec. 7.2.6, in Kypchak (1)

Stanitsa, 9th— 10th c., Sec. 7.2.7, in As-Alan, partly in lig. (4)

Mayak Smaller, 9th c., Fig. 7.2.10-1,5a,b, in Khazar (2)

Mayak Smaller, 9,h c., Fig. 7.2.10-3, in As-Alan (1) |

|

NG |

/ŋ/ |

Ermen Tolga, 8th — 10th c., Sec. 7.2.12, in Khazar (1)

Mayak Large Inscr., 9th c., Sec. 7.2.9, in Khazar (2) |

|

FORKED O |

/o/u/ |

Khumara, 9th-10th c„ Fig. 7.2.5-3, in Khazar (1)

Novocherkassk, 9th—10th c., Sec. 7.2.6, in Kypchak, glyph:

(1)

(1)

Village Krivyanskoe, Sec. 7.2.7, in As-Alan, glyph:

(6)

(6)

Mayak Large, Sec. 7.2.9, in Khazar, partly in lig.:

(4)

(4)

Mayak Smaller, Fig. 7.2.10-5a,b, in Khazar, in lig. (1)

Kievan Letter, 955-961, Sec. 7.2.15, in Khazar (1) |

|

P |

/p/ |

Achiktash, Sec. 7.2.4, in Kypchak, glyph: 3 (1) |

|

SIMPLE P |

/p/ |

Jitkov, first third of 8th c., Sec. 7.2.1, in Khazar (2)

Khumara, 9th—10th c., Fig. 7.2.5-4, in Ogur (1)

Minusinsk, 8th-9,h c., Sec. 7.2.8, in Turkic (2) |

|

ANGLED Q |

/q/uq/ |

Achiktash, 8th c., Sec. 7.2.4, in Kypchak, sound: /uq/ (2)

Homokmegy-Halom, Sec. 7.2.13, in Turkic, sound: /q/ (1) |

|

ARCHED Q |

/q/ |

Mayak Smaller inscr., 9th c., Fig. 7.2.10-1, in Khazar (1) |

|

OPEN Q |

/q/ |

Achiktash, first half of the 8th c., Sec. 7.2.4, in Kypchak (5) |

|

CLOSE Q |

/q/ |

Alsöszentmihâlyfalva, 920-952, Sec. 7.2.14, in Khazar (1)

Mayak Large Inscr., 9th c., Sec. 7.2.9, in Khazar (1)

Mayak Smaller, 9th c., Fig. 7.2.10-5a,b, in Khazar (1)

Kievan Letter, 955-961, Sec. 7.2.15, in Khazar, in ligature (1) |

|

R |

/r/ |

Mayaki Amphora, 8th-9th c., Sec. 7.2.2, in Ogur, glyph:

(2)

(2)

Novocherkassk, Sec. 7.2.6, in Kypchak, in ligature (2)

Alsöszentmihâlyfalva, 920-952, Sec. 7.2.14, in Khazar (2)

Mayak Large, 9th c., Sec. 7.2.9, in Khazar, glyph:

(2)

(2)

Mayak Smaller, Fig. 7.2.10-2, in Ogur, glyph:

(1)

(1) |

|

ARCHED R |

/r/ |

Achiktash, 8th c., Sec. 7.2.4, in Kypchak, glyph:

(5)

(5)

Village Krivyanskoe, 9,h— 10th c., Sec. 7.2.7, in As-Alan (1) |

|

CLOSE R |

/r/ |

Jitkov, first third of 8th c., Sec. 7.2.1, in Khazar (1)

Achiktash, first half of the 8th c., Sec. 7.2.4, in Kypchak (1)

Khumara, 9th—10th c., Fig. 7.2.5-lb,2b, in Khazar (2)

Khumara, 9th—10th c., Fig. 7.2.5-4, in Ogur (1)

Minusinsk, 8th-9th c., Sec. 7.2.8, in Turkic (3) |

|

ARCHED SH |

/ʃ/ |

Mayak Large, 9th c., Sec. 7.2.9, in Khazar (1) |

|

CIRCLE ENDED SH |

/ʃ/ |

Village Krivyanskoe, 9th-10th c., Sec. 7.2.7, in As-Alan (1) |

|

ZS (SH) |

/ʃ/ |

Jitkov, first third of 8th c., Sec. 7.2.1, in Khazar (1)

Devitsa Coins, 8th-9th c., Sec. 7.2.3, in Khazar, in ligature (2)

Novocherkassk, 9th-10th c., Sec. 7.2.6, in Kypchak (3)

Ermen Tolga, 8th—10th c., Sec. 7.2.12, in Khazar (4) |

|

SHL (SHL) |

/ɬ/ |

Bilyar, 1 l,h-13th c., Sec. 7.2.16, in Ogur (1) |

|

SZ (S) |

/s/ |

Jitkov, first third of 8th c., Sec. 7.2.1, in Khazar (1)

Khumara, 9th-10th c„ Fig. 7.2.5-4, in Ogur (1)

Homokmegy-Halom, 10th c., Sec. 7.2.13, in Turkic (2)

Mayak Large Inscr., 9th c„ Sec. 7.2.9, in Khazar (2)

Mayak Smaller, 9th c., Fig. 7.2.10-4, in As-Alan (1) |

|

FORKED SZ (S) |

/s/ |

Minusinsk, 8th-9th c., Sec. 7.2.S, in Turkic, simpler shape:

(1) (1)

Khumara, 7.2.5-2b,3, in Khazar, simpler shape (2)

Krivyanskoe, 9th-10th c., Sec. 1.2.1, in As-Alan (1)

Mayak Large Inscr., 9th c., Sec. 1.2.9, in Khazar (1)

Mayak Smaller Inscr., 9th c., Fig. 1.2.10-2, in Ogur (1) |

|

ARCHED T |

/t/ |

Khumara, 9th-10th c., Fig. 7.2.5-lb, in Khazar (1) |

|

CENTRAL T |

/t/ |

Khumara, 9th-10,h c., Fig. 1.2.5-4, in Ogur (1)

Krivyanskoe, 9' -10th c., Sec. 1.2.1, in As-Alan (1)

Mayak Smaller Inscr., 9th c„ Fig. 1.2.10-2, in Ogur (1) |

|

CLOSE T |

/t/ |

Bilyar, 11th-13th c., Sec. 1.2.16, in Ogur (1) |

|

OPEN T |

/t/ |

Achiktash, 8th c., Sec. 1.2.4, in Kypchak (8)

Khumara, 9th—10lh c., Fig. 1.2.5-lb,2b, in Khazar (4)

Mayak Large, 9th c., Sec. 1.2.9, in Khazar, glyph:

(1) (1)

Alsöszentmihâlyfalva, Sec. 1.2.14, in Khazar, in lig. (1) |

|

ARCHED UE |

/ø/y/ |

Bilingual Khazar Coin, Sec. 1.2.11, in Khazar, partly in lig. (2)

Ermen Tolga, 8th—10th c., Sec. 1.2.12, in Khazar, glyph:

(7) (7)

Mayak Large, 9th c., Sec. 1.2.9, in Khazar, glyph:

(2) (2) |

|

SHARP UE |

/ø/y/ |

Minusinsk, Sec. 1.2.8, in Turkic, glyph: N, sound: /y/ (3)

Khumara, 9th—10th c., Fig. 1.2.5-lb, 2b in Khazar, sound: /ø/ (2)

Alsöszentmihâlyfalva, Sec. 1.2.14, in Khazar, sound: /y/ (1) |

|

OPEN V |

/β/,

in Common Turkic at the beginning of the word: /b-/,

in As-Alan: /v/ |

Mayaki Amphora, 8th-9th c., Sec. 1.2.2, in Ogur (1)

Novocherkassk, 9th—10th c., Sec. 1.2.6, in Kypchak (1)

Krivyanskoe, 9th— 10th c., Sec. 1.2.1, in As-Alan (2)

Bilingual Khazar Coin, Sec. 1.2.11, in Khazar (1)

Ermen Tolga, 8th— 10th c., Sec. 1.2.12, in Khazar (2)

Mayak Fortress Large, 9th c., Sec. 1.2.9, in Khazar (1) |

|

CENTRAL Z |

/z/t/ |

Khumara, 9th—10th c., Fig. 1.2.5-3, in Khazar (1), sound: /z/

Krivyanskoe, Sec. 1.2.1, in As-Alan (1), sound: /z/

Minusinsk, Sec. 1.2.8, in Turkic (1), glyph:

sound: /t/

sound: /t/ |

| |

|

|

|

468 Hosszu 2011, pp. 6-8 & 34-35

142, 143, 144, 145, 146, 147

In KR relics the OPEN

V denoted /β/b-/v/. In current Turkic languages, /β/ also exists. For instance, in the Turkish Latin-based orthography, the character v represents /β/ in some cases.469 OPEN

V denoted /β/b-/v/. In current Turkic languages, /β/ also exists. For instance, in the Turkish Latin-based orthography, the character v represents /β/ in some cases.469

7.1.3. Diacritic mark and punctuation

There is only one known Khazar Rovas diacritic mark (Table 7.1.3-1); its role is signifying the end of the word. There also exist punctuation marks in KR (Table 7.1.3-2).

469 Gökser & Kerlake 2005, pp. 6-7

147 Table 7.1.3-1: The diacritic mark of KR

| Glyph |

Name of the KR character |

Examples of the glyph in relics |

|

COMBINING DOT ABOVE |

Novocherkassk, 9lh—10th c., Sec. 7.2.6, in Kypchak

Alsöszentmihâlyfalva, 920-952, Sec. 7.2.14, in Khazar |

Table 7.1.3-2: The Khazar Rovas separators and examples of each glyph in relics

| Glyph |

Name of the KR character |

Examples of the glyph in relics |

| • |

WORD SEPARATOR MIDDLE DOT |

Novocherkassk, 9th—10th c., Sec. 7.2.6, in Kypchak

Village Krivyanskoe, 9th—10th c., Sec. 7.2.7, in As-Alan

Minusinsk, 8th-9th c., Sec. 7.2.8, in Turkic

Alsöszentmihâlyfalva, 920-952, Sec. 7.2.14, in Khazar |

| : |

COLON |

Mayaki Amphora, 8th-9th c., Sec. 7.2.2, in Ogur

Ermen Tolga, 8th— 10th c., Sec. 7.2.12, in Khazar |

|

TRICOLON |

Village Krivyanskoe, 9th— 10th c., Sec. 7.2.7, in As-Alan |

| ı |

WORD SEPARATOR VERTICAL BAR |

Khumara 9th -10th c., Fig. 7.2.5-1b, in Khazar |

|

KHAZARIAN ROVAS

SEPARATOR LARGE |

Ermen Tolga, 8th— 10th c., Sec. 7.2.12, in Khazar

Minusinsk, Sec. 7.2.8, in Turkic with also a variant:

Mayak Large, 9th c., Sec. 7.2.9, in Khazar

Alsöszentmihâlyfalva, 920-952, Sec. 7.2.14, in Khazar |

7.1.4. Harmonization of consonants with vowels

The Khazar Rovas consonants are occasionally harmonized with the vowels of their syllables (Table 7.1.4-1). Oppositely to the Old Turkic consonants, this harmonization is not coherent.470 A consonant is called velar if it is used near back vowels, and it is called palatal if it is used near front vowels. The back (velar) and front (palatal) vowels are listed in

Table A-l. In some cases, the

Khazar Rovas characters of the velar-palatal consonant pairs were even exchanged, which is a unique feature of KR. Moreover, in the

Khazar Rovas inscription of the Mayaki Amphora (Sec. 7.2.2) the

R /r/ was used in both velar and palatal syllables.

(R is neither velar, nor palatial, i.e. neutral consonant) R /r/ was used in both velar and palatal syllables.

(R is neither velar, nor palatial, i.e. neutral consonant)

Table 7.1.4-1: Examples of the consonants being harmonized and not harmonized with the vowels of their syllables

Harmonized with back (velar) vowels

(called velar consonants) |

Harmonized with front (palatal) vowels

(called palatal consonants) |

Examples |

ARCHED

B /b/p/ ARCHED

B /b/p/ |

ANGLED B /b/,

ANGLED B /b/, RAISED B /b/ RAISED B /b/ |

Jitkov, 8th c., Sec. 7.2.1, in Khazar

Mayak Large, 9th c., Sec. 7.2.9, in Khazar |

ARCHED

D

/d/di/dɛ/j/dʒ/ ARCHED

D

/d/di/dɛ/j/dʒ/ |

SHARP D /d/ð/dʒ/ SHARP D /d/ð/dʒ/ |

Jitkov, 8 c., Sec. 7.2.1, in Khazar

Mayak Large, 9th c., Sec. 7.2.9, in Khazar |

, N GH /ɣ/ , N GH /ɣ/ |

CLOSE

G /g/ CLOSE

G /g/ |

Achiktash, 8th c., Sec. 7.2.4, in Kypchak

Minusinsk, 8th-9th c., Sec. 7.2.8, in Turkic

Mayak Large, 9th c., Sec. 7.2.9, in Khazar |

| N GH /ɣ/ |

FORKED

G /g/ FORKED

G /g/ |

Khumara, ca. 9th c., Fig. 7.2.5-4, in Ogur |

N /n/ N /n/ |

FORKED N /n/, FORKED N /n/, ANGLED N /n/ ANGLED N /n/ |

Khumara, ca. 9th c., Sec. 7.2.5, in Khazar

Mayak Large, 9th c., Sec. 7.2.9, in Khazar |

CLOSE

R /r/ CLOSE

R /r/ |

ARCHED R /r/ ARCHED R /r/ |

Achiktash, 8th c., Sec. 7.2.4, in Kypchak |

| (There is no occurrence in relics) |

CLOSE

R /r/ CLOSE

R /r/ |

Minusinsk, 8th-9th c., Sec. 7.2.8, in Turkic |

| (There is no occurrence in relics) |

, ,

R /r/

R /r/ |

Mayak Smaller inscription, 9th c. Fig. 7.2.10-2, in Ogur

Alsöszentmihâlyfalva, Sec. 7.2.14, in Khazar |

R/r/

R/r/ |

R/r/

R/r/ |

Mayaki, 8th-9th c., Sec. 7.2.2, in Ogur |

OPEN T /t/ OPEN T /t/ |

ARCHED T /t/ ARCHED T /t/ |

Khumara, ca. 9th c., Sec. 7.2.5, in Khazar |

| (There is no occurrence in relics) |

, ,  OPEN T/t/ OPEN T/t/ |

Achiktash, Fig. 7.2.4-1, in Kypchak

Minusinsk, Fig. 7.2.8-1, in Turkic

Mayak Large, Fig. 7.2.9-2, in Khazar |

470 Vekony 2004a, p. 193

148, 149

7.1.5. Ligatures

In Khazar Rovas, ligatures were frequently used. They are only stylistic, similarly to CBR ligatures (Sec. 6.1.5). However, two ligatures are systematic and used regularly

(Table 7.1.5-1):

DA and DA and

DI. The sound values of DI. The sound values of

DI are /de/, /di/, and

/ed/. Surely, its constituents are DI are /de/, /di/, and

/ed/. Surely, its constituents are ARCHED D /d/ and ARCHED D /d/ and ANGLED I. This supports that the ANGLED I. This supports that the ANGLED I originally represented both /e/ and /i/, despite of the fact that in the surviving KR relics, the ANGLED I originally represented both /e/ and /i/, despite of the fact that in the surviving KR relics, the ANGLED I represented /i/ only. It is noteworthy that in the Old Turkic script, which is also a descendant of the Early Steppe script, similarly to KR, the Old Turkic ANGLED I represented /i/ only. It is noteworthy that in the Old Turkic script, which is also a descendant of the Early Steppe script, similarly to KR, the Old Turkic

I represented both

/e/ and /i/ (Sec. 4.1). I represented both

/e/ and /i/ (Sec. 4.1).

Table 7.1.5-1: The systematic Khazar Rovas ligatures

| Glyph |

Name |

Transcription |

Constituents |

Examples of the glyph in relics |

|

DA |

/da/ |

ARCHED D

/d/ + ARCHED D

/d/ +

Y FORKED A /a/ |

Krivyanskoe, Sec. 7.2.7, in As-Alan, sound: /da/

Mayak Large, Sec. 7.2.9, in Khazar, sound: /da/

Mayak Smaller, Fig. 7.2.10-1, in Khazar, /da/ |

|

DI |

/de/di/ed/ |

ARCHED D

/d/ + ARCHED D

/d/ +

ANGLED I

/i/e/ ANGLED I

/i/e/ |

Humara, Fig. 7.2.5-4, in Ogur, sound: /di/

Alsöszentmihâlyfalva, Sec. 7.2.14, in Khazar, /ed/

Ermen Tolga, Sec. 7.2.12, in Khazar, sound: /de/

Mayak Large, Sec. 7.2.9, in Khazar, sound: /de/ |

149

Table 7.1.5-2 presents the non-systematic Khazar Rovas ligatures being applied on occasion.

| Glyph |

Name |

Transcription |

Constituents |

Examples of the glyph in relics |

|

AA |

/ʃi/, /iʃ/, /aa/ |

FORKED

E /a/ + FORKED

E /a/ + FORKED E

/a/ FORKED E

/a/ |

Village Krivyanskoe, Sec. 1.2.1, in As-Alan |

|

AN |

/an/ |

ARCHED E /a/ + ARCHED E /a/ +

N /n/ N /n/ |

Khumara, 9th—10th c., Fig. 1.2.5-3, in Khazar |

|

ATLIGH |

/ətliɣ/ |

OPEN

T /t/ + OPEN

T /t/ + SIMPLE

L /l/ + N GH /ɣ/ SIMPLE

L /l/ + N GH /ɣ/ |

Alsöszentmihâlyfalva, 920-952, Sec. 1.2.14, in Khazar |

|

BAN |

/ban/ |

RAISED

B /b/ + Y FORKED A /a/ + RAISED

B /b/ + Y FORKED A /a/ +

N /n/ N /n/ |

Mayak Smaller inscription, 9th c., Fig. 1.2.10-3, in As-Alan |

|

CSI (SHI) |

/tʃi/ |

TRIPLE

CS (SH/S) /tʃ/ + TRIPLE

CS (SH/S) /tʃ/ +

ANGLED I

/i/ ANGLED I

/i/ |

Khumara, 9th- 10th c., Fig. 1.2.5-4, in Ogur |

|

DKE |

/ðkɛ/ |

SHARP D

/ð/ + SHARP D

/ð/ +  FORKED K /k/ + FORKED K /k/ +

ARCHED E /ɛ/ ARCHED E /ɛ/ |

Jitkov, first third of 8th c., Sec. 7.2.1, in Khazar |

|

ER |

/ɛr/ |

FORKED E

/ɛ/ + FORKED E

/ɛ/ +  R

/r/ R

/r/ |

Novocherkassk, 9th—10th c., Sec. 1.2.6, in Kypchak |

|

IL |

/il/ |

ANGLED I

/i/ (mirrored glyph) + ANGLED I

/i/ (mirrored glyph) +

SIMPLE

L /l/ SIMPLE

L /l/ |

Kievan Letter, 955-961, Sec. 1.2.15, in Khazar |

|

IN |

/ïn/ |

ARCHED I /ï/

+ ARCHED I /ï/

+  FORKED

N /n/ FORKED

N /n/ |

Khumara, ca. 9th c., Sec. 1.2.5, in Khazar |

|

IQ |

/ïq/ |

ANGLED I

/i/ (mirrored glyph) + ANGLED I

/i/ (mirrored glyph) +

CLOSE Q /q/ CLOSE Q /q/ |

Kievan Letter, 955-961, Sec. 1.2.15, in Khazar |

|

JI |

/ji/ |

CLOSE J /j/ + CLOSE J /j/ +

ANGLED I

/i/ (mirrored glyph) ANGLED I

/i/ (mirrored glyph) |

Mayak Smaller inscription, 9th c., Fig. 1.2.10-4, in As-Alan |

|

ISHAD |

/iʃað/ |

ZS

(SH)

/ʃ/ + ZS

(SH)

/ʃ/ +  SHARP D

/ð/ SHARP D

/ð/ |

Devitsa Coins, c., Sec. 1.2.3, in Khazar |

|

NI |

/ni/ |

FORKED

N /n/ + FORKED

N /n/ +  ARCHED I /i/ ARCHED I /i/ |

Krivyanskoe, 9th— 10th c., Sec. 1.2.7, in As-Alan, ornamental |

|

NU 1 |

/nu/on/ |

FORKED

N /n/ + FORKED

N /n/ +  FORKED

O /u/ FORKED

O /u/ |

Krivyanskoe, Sec. 1.2.1, in As-Alan

Mayak Smaller inscription, 9th c., Fig. 1.2.10-5a,b, in Khazar |

|

NU 2 |

/nu/ |

N /n/

+ N /n/

+  FORKED

O /u/ FORKED

O /u/ |

Mayak Large, 9th c., Sec. 1.2.9, in Khazar |

|

ON |

/on/ |

FORKED

O /u/ + FORKED

O /u/ +

N /n/ N /n/ |

Mayak Large, 9th c., Sec. 1.2.9, in Khazar |

|

RAT |

/rat/ |

CLOSE R /r/ + CLOSE R /r/ + ARCHED E /ɛ/

+ ARCHED E /ɛ/

+

OPEN T

/t/ OPEN T

/t/ |

Khumara, ca. 9th c., Sec. 1.2.5, in Khazar |

|

SI |

/sï/ |

SZ

(S) /s/ + SZ

(S) /s/ + ANGLED

I /ï/ ANGLED

I /ï/ |

Achiktash, 8th c., Sec. 1.2.4, in Kypchak |

|

SHID |

/ʃið/ |

ZS

(SH)

/ʃ/ + ZS

(SH)

/ʃ/ + ANGLED

I /i/ + ANGLED

I /i/ + SHARP D

/ð/ SHARP D

/ð/ |

Achiktash, 8th c., Sec. 7.2.4, in Kypchak |

|

TEGH |

/teɣ/ |

OPEN

T /t/ + N GH /ɣ/ OPEN

T /t/ + N GH /ɣ/ |

Khumara, ca. 9th c., Sec. 7.2.5, in Khazar |

|

UED |

/øð/ |

ARCHED

UE /ø/ + ARCHED

UE /ø/ + SHARP D

/ð/ SHARP D

/ð/ |

Bilingual Khazar Coin, Sec. 7.2.11,

in Khazar in Khazar |

150, 151

7.2. Relics of the Khazar Rovas

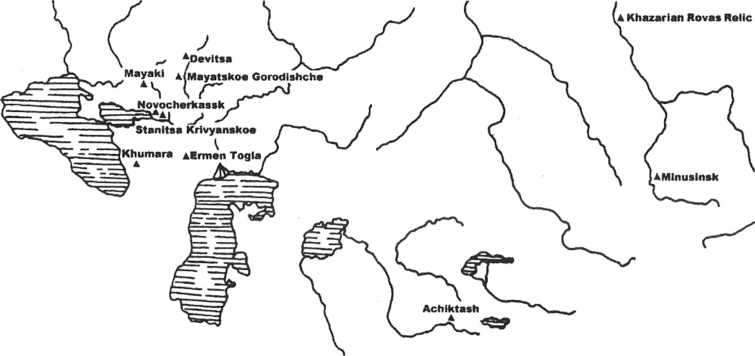

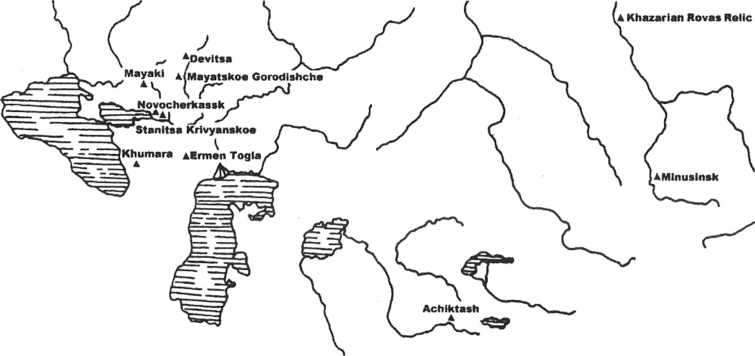

Map 7.2-1 presents the locations of KR archaeological finds in Eurasia. Most of the Khazar Rovas relics were found in the territory of the late Khazar

Kaganate, north of the Caucasus.

Map 7.2-1: Locations of the Khazar Rovas archaeological finds in Eurasia excluding the relics of the Carpathian Basin

7.2.1. Bow Cover of Jitkov

In 1986, Y. I. Bespalyi found a horn cover for a bow with a Rovas inscription in burial No. 1 of kurgan No. 4 on the field Jitkov II in the Rostov region.471 The relic is dated by some coin finds. Among them, there is a dirham from Nahr Tira dated to 716-717, and a solidus of Leo III (ruled in 717-720). These coins date the burial to the first third of the 8lh century.472

471 Semenov 1988, p. 109

472 TürkicWorld, web site

151

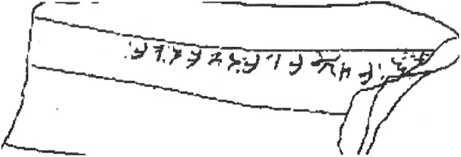

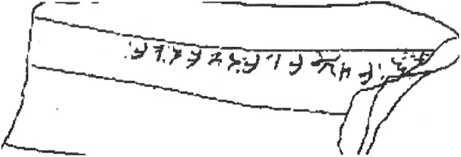

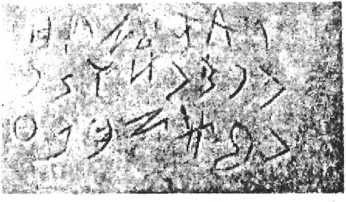

Figure 7.2.1-1: The inscription on the bow cover found at Jitkov, first third of the 8th century473

Table 7.2.1-1: Transcription of the Jitkov Inscription, first third of the 8th century

| Written with normalized Khazar Rovas font |

|

| IPA phonetic transcription |

|

|

Common Turkic (Khazar) |

Thkeib a xo ɣiyab ɣibe thib apaʒ n:aaraspa ɣaʒ shithi |

| Translation from Common Turkic (Khazar) |

‘We send Apsar Jap [the] bow. Shoot a mansion, wealth, oh to us!’ |

The ligature DKE /ðkɛ/ is composed of the followings:  SHARP D

/ð/ + SHARP D

/ð/ +  FORKED K /k/ + FORKED K /k/ +

ARCHED E /ɛ/. ARCHED E /ɛ/.

7.2.2. Mayaki Amphora Inscription in Ogur

The Mayaki Amphora Inscription was found in the motte-and-bailey

(citadel) of Mayaki, on the right bank of the Donets River. Its drawings were created by I. L. Kyzlasov

(Fig. 7.2.2-1 and 2). The amphora was made in the 8 - 9th centuries, when the fortress was used.

Figure 7.2.2-1: The Mayaki Amphora Inscription, 8th-9th centuries474

Figure 7.2.2-2: Another drawing of the Mayaki Amphora Inscription475 On this relic, the glyph

R /r/ - a variant of the

R /r/ - a variant of the  R /r/ was used. R /r/ was used.

Table 7.2.2-1: The transcription of the inscription on the Mayaki Amphora

| Written with normalized Khazar Rovas font |

[unreadable] [unreadable] |

| IPA phonetic transcription |

|

|

Common Turkic (Khazar) |

Nob merʒ nï naɣax rana |

| Translation from Ogur |

‘(This is) of Kagan Nar [or Anar], Twenty won.' |

473 Semenov 1988, p. 108

474 Klyashtomy 1979

475 Klyashtomy 1979

152

The Ogur word won was a measurement unit. The first two characters of the inscription were damaged; their transcription presumably is

bu. The name Nar (or Anar) was an ancient Turkic personal name.476 Since the transition /q/ > /x/ had been completed by the beginning of the 10th century in Ogur,477 the use of the word /xaɣan/ instead of the /qaɣan/ is explicable in the inscription.

The Oguz tribes moved into the Aral neighborhood at about 750, absorbing a spectrum

of the local

tribes known under a collective name Alans (Field or Steppe People, Polyans in Slavic) who were big on /h/ (/x/), it can

be expected that both the local version /xaɣan/ and the Oguz version /qaɣan/ remained in circulation

through the 10th c. and way beyond. The Arab (Moslem) writers used the form /xaɣan/, because that

form was used by the southwestern tribes they first encountered, or that was an Arabicized form due to

the specifics of the Arab phonetics. Either way, a quasi-scientific presumption on codified single

Oguz language, and the assertion that the blend of the local and migrant tribes spoke a common Oguz

language without dialectal differences, are pretentious fallacies. The -h- dialect of the

Aral basin followed Alans across Europe to Africa, and is prominant in the New World under a name

Castilian (Castellano) of the Argentinian Spanish.

|

7.2.3. The Devitsa Coins

In 1939, the Devitsa (also called Devica) treasure was found near the Don River. It contains 237 coins. According to Bykov, these coins are Khazar products

478 and their origin is between 754 and 811/812.479 This opinion is supported by scholars, especially Ludwig480 and Bâlint481

On several coins, the same ligature can be observed (Table 7.2.3-1)482

It means Ishad /iʃað/, the alternate name of the vice-king Ilik (i.e. Ulug,

aka Yilig, a short for Ulug-Bek, aka Bek, aka Kagan-Bek, a title of a

Prime Minister at a presiding Kagan) of the Khazar Kaganate.483 This inscription authenticated the coins. According to Golden,

Ishad (a Göktürk military rank used among southeastern tribes) is a version of an Iranian

(Persian?) dignitary name (title?).484 Based on these finds, the word

Ishad was used in the 8th- early 9th centuries. However, the dignitary name Ilik was used later, in the 10th century. Besides

Ishad and Ilik, there was a third name of the vice-king, namely

/bɛk/; its other form was /beg/.485

Table 7.2.3-1: The ligature of the Devitsa Coins from the 8th-9lh centuries and its transcription

| Ligature on the Devitsa Coins (glyph variations) |

|

| The elements of the ligature written with normalized Khazar Rovas font |

(SH)

/ʃ/

(SH)

/ʃ/  (I)

/i/ (I)

/i/ |

| IPA phonetic transcription |

/iʃað/ |

|

Common Turkic (Khazar) |

Ishath |

| Translation from Common Turkic (Khazar) |

‘Ishad’ |

Alternatively, the “ligature” was suggested to be a tamga of the ruler, in the Devitsa Hoard

of the Kagan Bulan (760-805), whose Beks were in sequence Bulan Sabriel (ca 740) and Obadia (ca

786-809). A name or a title-name of a subordinate minted on the coin would indicate a claim to

suzerinty and treated as a rebellion, an unlikely situation with two consequtive Beks under the sama

Kagan. Coin images (Fig. 21) and extracts from the table (Table 3) are cited from A.

Mukhamadiev, 2005, Ancient Coins of Kazan Kazan, Tatar Publishing house, ISBN 5-298-04057-8.

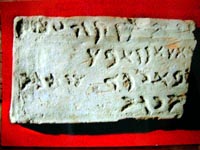

| Images of the Khazar coins |

| Fig. 21. Khazar dirham |

Khazar coin - immitation |

|

|

|

Khazar coin with Türkic runiform inscription

Found in Kaluga region (Central Russia) |

|

Türkic runes in the legend of this coin are not Orkhon or Enisei alphabet, but definitely from

Western areas (Southern Russia, Volga region, Northern Caucasus).

Attribution: Itil Bulgar or Khazar Kaganate (?), 9-10th c. (?) |

Table 3

Khazar imitations (Devitsky hoard)

| Coin type |

Coin dates |

Dating mark on reverse |

Reign years of rulers and existence of symbols |

Qty of coins |

Kagan and Bek |

Tamga |

| VIII |

150/767-68 |

Symbol of creed in two circles |

136-158 |

754-775 |

1 |

Bulan (760-805)/Bulan Sabriel (ca 740) |

|

| IX |

150/767-68 |

Ditto |

136-158 |

754-775 |

1 |

Bulan (760-805)/Bulan Sabriel (ca 740) |

|

| X |

150/767-68 |

al-Mahdi as heir |

145-158 |

762-63-775 |

1 |

Bulan (760-805)/Bulan Sabriel (ca 740) |

|

| XI |

150/767-68 |

Zur-p-riyasatain (Fadl ibn Sahl) |

196—205 |

811-12-820-21 |

38 |

Bulan (760-805)/Bulan Sabriel (ca 740) |

|

| XII |

162/778-79 |

Symbol of creed in two circles |

136-158 |

754-775 |

1 |

Bulan (760-805)/Obadia (ca 786-809) |

|

| |

837/838 |

Symbol of creed Musa rasul Allah “Moses is the Messenger of God” |

|

|

5 |

|

— |

|

|

476 Vekony 2004a, p. 272

477 Rona-Tas 1982b, pp. 163-164

478 Bykov 1971, pp. 26-35

479 Bykov 1971, pp. 65-66

480 Ludwig 1982, p. 274

481 Bâlint 1980, p. 384; Bâlint 1981. p. 410

482 Shake 2000, p. 35; Kovalev 2004, p. 113

483 Vekony 1997a, p. 28

484 Golden 1980, pp. 206 208

485 Golb & Pritsak 1982

153

7.2.4. The Achiktash Inscription from the Talas Valley in Kypchak

Fig. 7.2.4-1 presents the Achiktash Inscription (Wooden Stick of Talas) from the first half of the 8th century.

See

Codex_EuroAsiaticAchiktash_En.htm for details. The stick, buried under 5 m of soil in a well of

an old mine, should be assosiated with the mining population of the time, which for millennia is

anchored down by the deposits, and lives through all regimes. The mine bore tests showed 57% Fe, 4%

Cu, and 1% S, hence look for the iron-smith locals right on the main trace of the Silk Road (Ian

Blanchard, 2001, Mining, Metallurgy and Minting in the Middle Ages: Asiatic supremacy, Franz

Steiner Verlag, ISBN 9783515079587). The association with Kipchaks is more than dubious, but the

Saka Piedmonter tribes of the Türks, known as iron-smiths from the Chinese annals, are quite suitable (till the C14

analysis of the stick and the mine). The geographically nearest runiform inscriptions are the Issyk inscription

(4th c. BC) and Kultobe inscribed ceramic bricks of standard Middle Asian type 27x27x6 cm (4th-1st

cc. BC).

Issyk

|

Kultobe

|

|

Figure 7.2.4-1: The Achiktash Inscription (first half of the 8th c.)486

The inscription is on the four sides of a wooden stick. The stick was broken into three parts, but the middle one was never found. Therefore, the middle part of the text in each row is missing; the transcription is shown in Table 7.2.4-1

487 According to Vekony, the occasion for creating the inscription was probably the accession of a new ruler to the throne.488

In the inscription, the glyph

- a variant of the - a variant of the  ARCHED R /r/ and the glyph ARCHED R /r/ and the glyph

- a mirrored variant of the

- a mirrored variant of the  FORKED N /n/ were used. The glyph FORKED N /n/ were used. The glyph

was normalized as was normalized as  P /p/. P /p/.

Table 7.2.4-1: Transcription of the Achiktash Inscription

Written with normalized Khazar Rovas font

(right-to-left) |

|

IPA phonetic transcription

(left-to-right) |

|

Common Turkic (Khazar) transcription

(left-to-right) |

Tir ïthuq ethe ørin...

Qathɣuq hide itthïq oqïmïn mith....

Tegil aj suht osyt...

Hith qasar uthusï |

|

bïtïrh[ï(ɛ)ngïth]

ishihtibith qop

ɛrtɛr t[anïng] |

|

| Translation from the Kypchak |

‘He says: the throne of the holy dominus you write [singular or plural] We ... reading the written stick sent by you we all heard it Ay! Say it: Sogdian vengeance ... avoid [you], [you] k[now] You, Khazars. Good (= true, credible). End.’ |

Ay was a personal name meaning ‘Moon’ in Proto-Turkic (what

“Proto-Turkic” means?). In the fourth row, the name Khazar is found:

/qasar/ ‘Khazar’ and the name of the Sogdians is in the third row: /qasar/ ‘Khazar’ and the name of the Sogdians is in the third row:

/suht/ ‘Sogdian’. Vekony supposed that in this inscription, the KR /suht/ ‘Sogdian’. Vekony supposed that in this inscription, the KR

TRIPLE CS

(SH/S) /tʃ/ represents /s/.489 This is possible, if the /tʃ/ > /s/ change happened in the language of this inscription. For instance, such a transition occurred in the Bashkir language.490 TRIPLE CS

(SH/S) /tʃ/ represents /s/.489 This is possible, if the /tʃ/ > /s/ change happened in the language of this inscription. For instance, such a transition occurred in the Bashkir language.490

486 Vekony 2004a, p. 287

487 Vekony 1986, Fig. 1

488 Vekony 2004a, p. 293

489 Vekony 2004a, p. 294

490 Vâsâry 2010-2011

154

7.2.5. The Khumara building inscriptions

Khumara is an old Khazar fortress on the right hand side of the Kuban River, currently in the Karachay-Cherkess Republic (Russia). The Khumara Fortress was near to a very important road, which was the main artery between Khwarezm and Byzantium in the Early Medieval Times.491 The total area of the huge fortress was a quarter km2, the total length of its walls reached 1900 meters. A.V. Gadlo showed that the fortress was built in the beginning of the 8th century.492 Fig 7.2.5-1 a presents the photograph of a building inscription on a sandstone block found in 1962, and Fig.

7.2.5-lb shows its drawing. The original stone was re-used for the construction of the fortification wall and it was broken into two pieces. The origin of the inscription is between the mid-9,h century and beginning of the 10th century.493

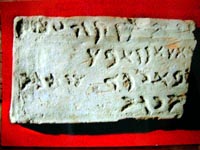

Figure 7.2.5-la: Photograph of the One-row Inscription on a fragment of a sandstone block, between middle of the 9th and 10th centuries494

Figure 7.2.5-lb: Drawing of the One-row Inscription495

Table 7.2.5-1: Transcription of the One-row Khazar Rovas Inscription of Khumara

| Written with normalized Khazar Rovas font |

|

| IPA phonetic transcription |

|

|

Common Turkic (Khazar) transcription

(left-to-right) |

øth tegin daratï |

| Translation from Common Turkic (Khazar) |

‘Öd Tegin made [it].’ |

The word  /darati/ is the ancestor of the Hungarian word

gyârt /da:rt/ ‘produce, make’. The Öz /øz/ is a well-known Turkic personal name.496 According to Vekony, the transition

/z/ > /ð/ (/th/) happened in Khazar. Therefore, Öd /øð/

(/öth/) was identical with Öz /øz/. The /tegin/

(Prince) was a Khazar title (dignitary name). There is an example for this dignitary name in the sources: the name “Er Tegin” from the 680s.497 In the Western Turkic

Kaganate, the title tegin was also used, as it is attested to in inscriptions found in East Iran.498 The word

tegin survived as a personal name in the 10th century: a leader of the Magyars was called Teteny (its other form:

Tühütüm).499 This name can be found in the name of

Teteny Village (present-day Tadten in Burgenland, Austria) near the Lake Ferto, in the name of

Tattendorf 'Tatten Village’ (present-day east of Vienna, Austria) near the Triesting River, and in the name of Budapest District 22: Nagyteteny ‘Great Teteny’.500 /darati/ is the ancestor of the Hungarian word

gyârt /da:rt/ ‘produce, make’. The Öz /øz/ is a well-known Turkic personal name.496 According to Vekony, the transition

/z/ > /ð/ (/th/) happened in Khazar. Therefore, Öd /øð/

(/öth/) was identical with Öz /øz/. The /tegin/

(Prince) was a Khazar title (dignitary name). There is an example for this dignitary name in the sources: the name “Er Tegin” from the 680s.497 In the Western Turkic

Kaganate, the title tegin was also used, as it is attested to in inscriptions found in East Iran.498 The word

tegin survived as a personal name in the 10th century: a leader of the Magyars was called Teteny (its other form:

Tühütüm).499 This name can be found in the name of

Teteny Village (present-day Tadten in Burgenland, Austria) near the Lake Ferto, in the name of

Tattendorf 'Tatten Village’ (present-day east of Vienna, Austria) near the Triesting River, and in the name of Budapest District 22: Nagyteteny ‘Great Teteny’.500

The speculation on /z/ > /ð/ (/th/) transition conflicts with attestation

that interdental th was widespread in the Old Türkic, depicted as δ in transcriptions,

and in the old Türkic Horesmian, depicted as

and identical to the Futhark Þþ. Likely, the transition went in opposite way, the

alien speakers were adopting the Türkic th in a veriety of approximations, including /z/, /t/, /d/,

and /f/.

and identical to the Futhark Þþ. Likely, the transition went in opposite way, the

alien speakers were adopting the Türkic th in a veriety of approximations, including /z/, /t/, /d/,

and /f/.

|

491 Erdelyi 1983b, p. 264

492 Gadlo 1979, pp. 152-153

493 Baichorov 1989, p. 67, pp. 170-173; Türkic World, web site

494 Kuznetsov 1963, Fig. 2 -2

495 Vekony 1987a, p. 27; Vekony 2004b

496 Nadeljaev et al (ed.) 1969, p. 395

497 Golden 1980, pp. 186-187

498 Harmatta 1994, pp. 149-164

499 Györffy 1998, p. 135

155

Figure 7.2.5-2a: Photograph of Three-row Inscription from the Khumara fortress501

The meaning of the One-row Inscription in Fig. 7.2.5-1a matches the first row of the inscription of the

Fig. 7.2.5-2a. In the first row of Fig. 7.2.5-2a, the second symbol

on the left is a ligature of the characters on the left is a ligature of the characters  CLOSE

R /r/, CLOSE

R /r/, ARCHED E /a/,

and ARCHED E /a/,

and

OPEN T

/t/. These characters were used as individual glyphs in Fig. 7.2.5-la. In the third row, the ligature OPEN T

/t/. These characters were used as individual glyphs in Fig. 7.2.5-la. In the third row, the ligature

contains contains

OPEN T

/t/ and N GH /ɣ/. OPEN T

/t/ and N GH /ɣ/.

In the word

/teɣine/ there are

front vowels. However, in other parts of this Three-row Inscription, the /teɣine/ there are

front vowels. However, in other parts of this Three-row Inscription, the  CLOSE G /g/ was applied near

front vowels and another character N GH /ɣ/ is used near back vowels. The probable reason of this inconsistency is that CLOSE G /g/ was applied near

front vowels and another character N GH /ɣ/ is used near back vowels. The probable reason of this inconsistency is that OPEN T

/t/ and N GH /ɣ/ was easier to apply to create the ligature OPEN T

/t/ and N GH /ɣ/ was easier to apply to create the ligature

. Another example for altering the velar and palatal consonants is the use of the velar . Another example for altering the velar and palatal consonants is the use of the velar OPEN T

/t/ in the first row instead of the palatal OPEN T

/t/ in the first row instead of the palatal ARCHED T /t/. It is noteworthy that in this case the ARCHED T /t/. It is noteworthy that in this case the OPEN T

/t/ was not used in ligature. To summarize, this inscription demonstrates the inconsistent use of the velar and palatal consonants in KR (Sect. 7.1.4). OPEN T

/t/ was not used in ligature. To summarize, this inscription demonstrates the inconsistent use of the velar and palatal consonants in KR (Sect. 7.1.4).

A tendency to blame scribes and carvers is a longstanding philological tradition. A

lazy carver may not be a culprit, though. Most of the time, a palatal syllable carries a different

meaning from the velar syllable, and to confuse them is akin to replacing red stripes with green

stripes on a national flag, that completely changes the message. A few words have two versions, one

with palatal phonetics, and the other with velar phonetics. Frequently, these few words also contain

neutral syllables, and can be swung either way. Absent that, different meanings should theoretically

be suspected for tegine /tegine/

and täkïnä /təkïnə/ before invoking a lazy carver. In the end, the

linguistic and phonetical attributions of the carvings and the use of ligatures are conditional on

what is not known.

|

Figure 7.2.5-2b: Drawing of the Three-row Inscription502

500 Bartha 1984, p. 577; Györtly 1998, p. 135; Zelliger 2010-2011

501 Kuznetsov 1963, Fig. 2-2

502 Vekony 2004b

156

Table 7.2.5-2: Transcription of the Three-row Inscription of Khumara

| Written with normalized Khazar Rovas font |

|

| IPA phonetic transcription |

|

|

Common Turkic (Khazar) transcription

(left-to-right) |

ød tegin daratï

thïnïmïthïɣ asman

øthyg teɣine aj |

| Translation from Common Turkic (Khazar) |

‘Öd Tegin (had it) made our nest [=home], As(es). Call it Ödüg Tegin.' |

Table 7.2.5-2: Transcription of the Three-row Inscription of Khumara

The drawing in Fig. 7.2.5-3 was made by the student A.D. Besleneev on his summer holiday; hence, its accuracy is possibly limited. There is no photograph of the original relic, since it was destroyed before the arrival of the archaeologists.503 In the inscription, the glyph

0 is a variant of D CLOSE J /j/. The word /aj/ means ‘speak, say, call’ in Turkic. The word /*asman/ probably mean ‘As’ or ‘Ases’, since /as/ was the name of the As-Alans and /man/ is a Turkic affix emphasizing the meaning (nation or tribe name).

(It could also mean various types of rams, like a castrated ram; the idea

on Ases comes from Ases being a tribe of what collectively was called Alan “Steppe-men, Flatlander”;

the modern reference to Ases may be too politicized)

Text is rich in information: the Khazar fortress of Khumara was built by Öd Tegin; therefore, it was named Ödüg Tegin. In the name of Ödüg, the

/g/ is the voiced version of the Turkic diminutive suffix /k/. There are other examples for this structure: personal name + title > geographical name. For instance, Phanagoria (the ancient Greek colony on the Taman peninsula between the Black Sea and the Sea of Azov) has an alternative name: /tamyantarqan/, in which the /tarqan/ is a title (dignitary name).

Figure 7.2.5-3: Drawing of the Two-row Inscription from Khumara Fortress505

Table 7.2.5-3: Transcription of the Two-row Inscription of Khumara

| Written with normalized Khazar Rovas font |

|

| IPA phonetic transcription |

|

|

Common Turkic (Khazar) transcription

(left-to-right) |

ïnumuzuɣ, asman

øththün ebine aj |

| Translation from Common Turkic (Khazar) |

‘Our nest [=home], As(es), call it mansion of Ödün.' |

The inscription in Fig. 7.2.5-3 equals to the second and third rows of the inscription of the

Table 7.2.5-2. However, there are dialectical differences between the Table 7.2.5-2 and

3. For instance, in the first row in Table 7.2.5-3  CENTRAL

Z /z/ was used instead of CENTRAL

Z /z/ was used instead of  SHARP

D /ð/ in Table 7.2.5-2. A similar dialectical difference is between /ïn/ in Table 7.2.5-3 and /ðïn/ in

Table 7.2.5-2. SHARP

D /ð/ in Table 7.2.5-2. A similar dialectical difference is between /ïn/ in Table 7.2.5-3 and /ðïn/ in

Table 7.2.5-2.

503 Kuznetsov 1963, Fig. 3-1; TürkicWorld, web site

504 Ligeti 1958. p. 448; Ligeti 1977, p. 78, Kononov 1980, p. 96

505 Vekony 2004b

157

The ligature

was composed of was composed of  ARCHED I /ï/ and ARCHED I /ï/ and  N /n/,

the auxiliary slanted line was presumably applied in order to differentiate it from ) N /n/,

the auxiliary slanted line was presumably applied in order to differentiate it from )  ARCHED

E /a/. The /n/ in the word Ödün was probably a diminutive suffix.

(There is something alarming about similarity of the name Ödün of the Caucasus Ases and

the name Odin of the Scandinavian Ases, both of the princely variety) ARCHED

E /a/. The /n/ in the word Ödün was probably a diminutive suffix.

(There is something alarming about similarity of the name Ödün of the Caucasus Ases and

the name Odin of the Scandinavian Ases, both of the princely variety)

The inscription in Fig. 7.2.5-4 is fragmentary; its transcription needed a reconstruction (drawing of the archaeologist G. Vekony based on A.M. Shcherbak’s

publication).506

Figure 7.2.5-4. Drawing of a fragmentary inscription from Khumara Fortress.507

On this relic, the glyph

- a mirrored variant of the

N GH /ɣ/ was used. - a mirrored variant of the

N GH /ɣ/ was used.

Table 7.2.5-4: Transcription of the One-row Ogur Inscription of Khumara

| Written with normalized Khazar Rovas font |

|

| IPA phonetic transcription |

|

|

Common Turkic (Khazar) transcription

(left-to-right) |

tuɣalas, ʒapdi, bishigi ïr |

| Translation from Ogur |

‘Tughalas made (built?), wrote its inscription.’

or:

‘N. Tughalas made (built?), wrote its inscription.’ |

The word /tuɣalas/ is an ethnic name according to Ibn Rustah.508 The last word

/ïr/ is the Ogur version of the Common Turkic verb /yaz/ ‘draw’.509 The evidence of the existence of the Ogur verb

/ïr/ is the Hungarian verb ir /i:r/ ‘write’.510

The verb /ʒapdi/ (< Proto-Turkic /yap/) means ‘built, did’, the KR  SHARP

D is transcribed with /ʒ/, supposing (suggesting) that the inscription is in Ogur. The word /bitʃig/ is the Ogur version of the Common Turkic /bitig/.511 Since the

Tughalas /tuɣalas/ can be an ethnic name, it could also be a personal name. Moreover, since the beginning of the inscription is broken, the “<Personal name>, the Tughalas” structure is also a possible interpretation. An uncertainty of the transcription is the ligature SHARP

D is transcribed with /ʒ/, supposing (suggesting) that the inscription is in Ogur. The word /bitʃig/ is the Ogur version of the Common Turkic /bitig/.511 Since the

Tughalas /tuɣalas/ can be an ethnic name, it could also be a personal name. Moreover, since the beginning of the inscription is broken, the “<Personal name>, the Tughalas” structure is also a possible interpretation. An uncertainty of the transcription is the ligature

/di/ in the reconstruction of the word /di/ in the reconstruction of the word

>

/dʒapdi/ ‘made’, since the lower part of the ligature is damaged. >

/dʒapdi/ ‘made’, since the lower part of the ligature is damaged.

The described specifics of the Ogur vs. Oguz (aka Common Turkic) variety suggests

that the Oguz form with a prosthetic semi-consonant is an Ogur form /yaz/, adopted into Oguz

languages with the anlaut semi-consonant and preserved there, while the form /ïr/ in the

inscription reflects the loss of the initial semi-consonant typical for the Oguz languages. With the

north/south divide between the Oguz and Ogur, that would indicate that the Türkic term “write”

originated in the south-west. The verb /ʒap-/ would be a conforming Ogur form with anlaut

prosthetic consonant for the Oguz counterpart with anlaut semi-consonant /yap/ that has nothing to

do with the mythical “Proto-Turkic”

language. The /t/ <=> /tʃ/ is a non-specific dialectal alteration, it arises under an influence of

palatalized speech, like Chuvash and Slavic.

The ethnonym Taulas is still active, Taulases occupy the summit area at the

Daryal Pass on its southern side. The tau/tag/taɣ/tug stands for “mountain”,

-l- is an adjectival suffix a la “mountainous”, and -as is the ethnonym “As”, i.e. “Mountain

As”; the reconstructed t(a)uɣ[a]l + as does not need the suggested bracketed

[a], i.e

Tauglas. That a Taulas was noted in inscription is natural for a migrant, everybody else on the

construction crew was not from the Taulases. The modern Taulases can't be confused with the

historical Taulases. The modern Taulases are predominantly descendents of the local Adyge

population, of G2 Y-DNA variety (G2a1a1), that migrated from the Old Europe 4000 ybp, their

Adyge-type language is now the Ossetian language. The small admixture of R1a and R1b haplogroups are

the relicts of the historical As population that gave its name to the modern Taulases.

|

7.2.6. Novocherkassk Clay Flask Inscription in Kypchak

A clay flask with two handles was found during the construction of Salsk-Tsaritsyn (currently Volgograd) railroad in 1909.512 There are similar flask finds from around Novocherkassk with typical dimensions: width is no larger than 8 cm; diameter is about 30-35 cm. According to Artamonov, the origin of the clay flask on the

Fig. 7.2.6-1 is the 9th - 10th centuries. Under the right handle, on the convex side of the flask, there is a KR inscription.

Fig. 7.2.6-1 shows its photograph, and Fig. 7.2.6-2 presents its drawing.

506 Shcherbak 1962, Fig. 1

507 Vekony 2004b

508 DeGoeje, M. J. fed.) 1892

509 Vâsâry 2010-2011

510 Pallö 1982. p. 111-113

511 Röna-Tas 1992, pp. 12-13

512 Artamonov 1954, p. 264

158 Figure 7.2.6-1: The Novocherkassk Inscription (9th-10th centuries)513

Figure 7.2.6-1: The drawing of the Novocherkassk Inscription.514

On this relic, the glyph

- a variant of the

- a variant of the FORKED

O /o/u/ was used. FORKED

O /o/u/ was used.

Table 7.2.6-1: Transcription of the Novocherkassk Inscription.

The transcription of the archaeologist-historian G. Vekony 515 was modified by Turkologist I. Vâsâry in 2011. 516

| Written with normalized Khazar Rovas font |

|

| IPA phonetic transcription |

|

|

Common Turkic (Kypchak) transcription

(left-to-right) |

aishermith bith ishermith boshadin |

| Translation from Common Turkic (Kypchak) |

‘Oh. Let us drink. We drink from [this] bosha.’ |

The word bosha was the name of a fermented alcoholic drink; Sec. 6.2.9 presents the genealogy of the word. In this case, the OPEN

V probably represented /b-/, since the inscription was written in Common Turkic, where in the beginning of the word /b-/ was pronounced instead of /β-/.517 The word /-dïn/ is a Turkic ablative suffix, meaning ‘from’. OPEN

V probably represented /b-/, since the inscription was written in Common Turkic, where in the beginning of the word /b-/ was pronounced instead of /β-/.517 The word /-dïn/ is a Turkic ablative suffix, meaning ‘from’.

7.2.7. Village Krivyanskoe Clay Flask Inscription in Preossetic (As-Alan)

In May 1942, a clay flask was discovered, at a depth of 1.5 meters, near Village Krivyanskoe (Fig. 7.2.7-1).518 Its inscription was published by Artanomov in 1954, with the original punctuation by Turchaninov in 1964 and in 1971.519 Figure

7.2.7-2 shows Turchaninov’s drawing.

513 Baichorov 1989, Table 113

514 Vekony 2004a, p. 243

515 Vekony 2004a, pp. 243-252

516 Vâsâry 2010-2011

517 Vâsâry 2010-2011

518 Artamonov 1954, p. 263-268

519 Turchaninov 1964 & 1971

159 Figure 7.2.7-1: The photographs of the

Village Krivyanskoe Inscription (9th—10th centuries)520

Figure 7.2.7-2: The drawing of the Village Krivyanskoe Inscription.521

On this relic, the glyph

-a variant of the

-a variant of the FORKED O /o/u/ was used. FORKED O /o/u/ was used.

Table 7.2.7-1: Transcription of the Village Krivyanskoe Inscription

| Written with normalized KR font |

|

| IPA phonetic transcription |

|

|

Common Turkic (Kypchak?) transcription

(left-to-right) |

voshudanu thabu danu charith niuazag thaxichan uacheg bafistaa |

| Translation from As-Alan (Preossetic) |

‘[This] voshu drink is yours. [This] drink should keep alive [the] one who drinks [it]. For you, Uachag wrote this.’ |

In this relic, the form voshu of the drink boza (English

booze) occurs;522

Sec. 6.2.9 presented the genealogy of this word. The sound /a/ was a Preossetic common

determiner, meaning ‘this’. This /a/ is written in the duplication of FORKED

E /a/ ( FORKED

E /a/ ( /a-a/ at the end of the row, where the other /a/ is the last vowel of the word /bafista/. In the inscription at the end of the word /niuzag/, there is the diacritic mark o COMBINING DOT ABOVE, a specific

Khazar Rovas word separator. The use of this separator in the inscription was probably occasionally mixed with the other

Khazar Rovas separator, the /a-a/ at the end of the row, where the other /a/ is the last vowel of the word /bafista/. In the inscription at the end of the word /niuzag/, there is the diacritic mark o COMBINING DOT ABOVE, a specific

Khazar Rovas word separator. The use of this separator in the inscription was probably occasionally mixed with the other

Khazar Rovas separator, the

TRICOLON. TRICOLON.

What is “Preossetic” one God knows. Probably it is a reverse projection of a

blend of the modern Ossetic languages, then it is a mixture of the Adyge (Y-DNA G2a1a1) and Near

Eastern (Y-DNA J2) substrate of the Ossetic, impregnated with few Turkisms accumulated for the past

1700 years. If it is an allusion to the Türkic language of Ases or Alans, or the much later

Kipchaks, the enigma just grows bigger. The very term used, “Preossetic”, attests that the language

has nothing to do with the Khazars and their multi-variegated Türkic ilk, including the Ases or

Alans.

|

7.2.8. Spindle Disk of Minusinsk

In 1948, a rounded stone of a spindle was explored during the archaeological excavations of V.P. Levasova near Minusinsk. The relic is from the 8th

- 9th centuries, currently preserved in the Minusinsk Museum.523 There are Old Turkic symbols on the flat surfaces of the spindle disk, and there is a

Khazar Rovas inscription on its arched lateral surface. Fig. 7.2.8-1 presents the photograph of the spindle disk,524 and

Fig. 7.2.8-2 shows the drawing and the transcription made by Vekony.525 The transcription was improved by Vâsâry.526

520 Baichorov 1989, Table 116

521 Turchaninov 1964, pp. 83 -84 & 1971, pp. 75-77

522 Vekony 2004a, p. 257

523 Vasilev 1983, p. 40, No. E-87

524 TÜRIK BITIG, web site

525 Vekony 2004b

526 Vâsâry 2010-2011

160

Figure 7.2.8-1: The photograph of the spindle disk of Minusinsk

Figure 7.2.8-2: The copy of the inscription broken into two rows

On this relic, the glyph variant

of the

of the CIRCLE

ENDED I /i/ï/, CIRCLE

ENDED I /i/ï/,

of the of the SHARP UE /y/, SHARP UE /y/,

of the

of the CENTRAL

Z /z/t/, and the mirrored glyph CENTRAL

Z /z/t/, and the mirrored glyph

of the

N GH /ɣ/ were used. The glyph

of the

N GH /ɣ/ were used. The glyph

- a variant of the symbol - a variant of the symbol

KHAZAR ROVAS SEPARATOR LARGE was also used on this relic.

KHAZAR ROVAS SEPARATOR LARGE was also used on this relic.

Table 7.2.8-1: Transcription of the Inscription of Minusinsk.

| Written with normalized Khazar Rovas font |

|

| IPA phonetic transcription |

|

|

Common Turkic (Kypchak) transcription

(left-to-right) |

ipjig jygyrryg

ørtylmeth (ürtülmiş(le:rke:) Clauson p. 209) (a)suɣapam |

| Translation from Turkic |

‘(This) thread-spindle [is] fast. My aunt (A)sugh does not hide.’ |

An interesting specialty of this relic is that the fifth character from the right and the last (leftmost) character of the first row in

Fig. 7.2.8-2 are corrected: the writer earlier wrote  TRIPLE GH /ɣ/ in both cases, and then corrected them with TRIPLE GH /ɣ/ in both cases, and then corrected them with CLOSE G

/g/. In other words, the writer first used the fricative /ɣ/, and then it was corrected to the plosive

/g/. The personal name in the inscription can be either Asugh /asuɣ/ or Sugh /suɣ/.

(örtül-/ürtül- is passive of “conceal, cover, hide” > “concealed by

my Asug-apa”) CLOSE G

/g/. In other words, the writer first used the fricative /ɣ/, and then it was corrected to the plosive

/g/. The personal name in the inscription can be either Asugh /asuɣ/ or Sugh /suɣ/.

(örtül-/ürtül- is passive of “conceal, cover, hide” > “concealed by

my Asug-apa”)

161

7.2.9. Mayak Fortress Large Building Inscription

In 1978, during the Soviet-Hungarian-Bulgarian common excavations of the Mayak Fortress (‘Stone Castle of

Mayak’, other name: Mayaki citadel), S.A. Pletneva and G.E. Afanasyev found the longest known KR inscription.527 The citadel was built in the 9th century; the city itself existed from the end of the 8th century and it belonged to the territory of the As-Alans.528.

Fig. 7.2.9-1 a and b are drawings of the architect B. Erdelyi, a participant in the excavation.529

Figure 7.2.9-la, b: Drawings of the Inscription of Mayak Fortress by architect B. Erdelyi.

On

this relic, the glyph variants

of the

of the FORKED

O /o/u/, FORKED

O /o/u/,

of the of the DIAGONAL E /ɛ/, and DIAGONAL E /ɛ/, and

of the of the  ARCHED UE /ø/y/ were used. ARCHED UE /ø/y/ were used.

| a) |

b) |

|

|

527 Erdelyi 2004a, p. 76

528 Erdelyi 1991

529 Kyzlasov 1990; p. 16

162

Figure 7.2.9-2: The drawing of the Inscription of Mayak Fortress reconstructed by archaeologist G. Vekony

The ends of the first and second rows may show characters of a different script; those were probably engraved later.

Table 7.2.9-1 presents the transcription of the inscription.530

Table 7.2.9-1: Transcription of the Large Building Inscription of Mayak Fortress

| Written with normalized Khazar Rovas font |

|

| IPA phonetic transcription |

|

Common Turkic (Khazar) transcription

(left-to-right) |

danu aq öthyg

sub asil echim xaɣan bithing deribith alti saβïrïng [...]

uth dithy on munda ilte ygysh isig bedithedi ol dathu ineg [...]

onaɣ tegin ebi ög |

| Translation from Common Turkic (Khazar) |

First row: 'Don [River], white Ödüg River, As Country, [oh] my brother-khagan, our land of the Six-Savirs ...’

Second row: ‘Ud Didü On, here, in [this] country, ornamented several works. This inscription made by Ineg...’

Third row: ‘Mansion of Onagh Tegin. Extol it.’ |

First row: Danu is the Don River in the As-Alan language. The Aq means white; this is probably the attribute of the following river-name

Ödüg or the name of another river. Ödüg is the Khazar name of the Dnieper River.531 The /alti

saβïr/ ‘Six-Savirs’ is the name of a nation, as in the Turkic languages, the ethnic name made of the structure of number+name is typical, e.g., Onogur ‘Ten-Ogurs’. According to the historian al-Mascüdi (10th century), the Turks called the Khazars Savirs.532 Based on this data, in this Rovas inscription, the alternative name of the Khazars was ‘Six-Savirs’. According to the author of this book, the original ethnic name could have been the Six-Savirs if the ethnic name Khazar originated from the Roman title Caesar as Röna-Tas stated (Sect. 3.5.1).533 In the last word (from the right), the character between R /r/ and R /r/ and NG

/ŋ/ is hard to read; Vekony reconstructed it as NG

/ŋ/ is hard to read; Vekony reconstructed it as ARCHED I /ï/. ARCHED I /ï/.

The parsing of the inscription is heavy on nouns and light on morphology, resembling other

unsuccessful reconstructions with spurious flavor. Typical Türkic phrase is heavy on conjugations

and declensions, and light on nominals and verbs. In addition to being reasonable phonetically, a

phrase must also make sense.

In Türkic don is “cold, icy”, Herodotus said: “icy Tanais”, hence here the inscription

says in Savir language “icy, white”. Nobody knows what was the As-Alan name for Don, the inherited

from the locals default

As-Alan name is also the Türkic Don “cold, icy”. The conflation of the names As, a part

of the known As-Tokhar confederation, and the umbrella term Alan “Steppe-man, Flatlander” is

disturbing. Tokhars, for example, were Alans, but not the Ases.

From Herodotus times to end of the 10th c. AD the local name for

Dnieper, and also for Buh, was a range of allophones, reflexes, and calques: from Βορυσθένης (Borusthenes),

Borysthenes to Burichai, meaning “Bear stream”. The Buh was discriminated by adjective “White”: Κουβοΰ “White

Winding”, where Kuu is “White”. Khazars were not natives of the Dnieper basin, it is inconceivable that they

would come up with new names for old places of common knowledge. Ödüg in the inscription may be “selected,

chosen” river, i.e. a fort on the suitable river, cf. ödür- “select, choose”. That

is, if the parsing is accurate.

The Arabs called Savirs, and numerous other

ethnically non-Khazar people, Khazars. Savirs (Suvars) are known in the Caucasus much earlier

than the Khazars, and they were a ruling tribe before the advent of the Khazars. The Arabs, like the

Khazars, were late comers, the Arab term Khazar is solely political and separate from the

ethnic terms. The term Savir is ethnic and political, in addition to being specifically

ethnic, it also covered numerous ethnicities in the Savir domain: Kayis, Masguts/Massagets/Alans,

Huns, Bulgars, etc., and all local sedentary tribes.

The Six-Savirs confederation has no relation to the Khazars other

than it has transferred to the Khazar Kaganate their suzerain authority after their capital Samandar

was taken by the Arab commander Maslama in course of 727/728 campaign.

Whatever speculations on the origin of the name Khazar are, the names Khazar and Six-Savirs

are not related other than by political correlation.

|

Second row: Ud Didü On /uð diðy °n/ was a personal name. Another possible transcription of    /diðy/ is /didy/. This was one of the Khazar versions of the ethnic name Jewish. Its other version was found in the Alsöszentmihâlyfalva Inscription (Fig. 7.2.14-2). Both words originated from Hebrew.534 /diðy/ is /didy/. This was one of the Khazar versions of the ethnic name Jewish. Its other version was found in the Alsöszentmihâlyfalva Inscription (Fig. 7.2.14-2). Both words originated from Hebrew.534

Here we have another disconnect: Suvars would unlikely use a Hebrew word for Jews

when they have a Caucasian lingua franca word Djuga (cf. Djugashvilli “Son of Jew”) , known and

understood by everybody in the Caucasus. The ud or uth is “cow”, on is “ten”,

as a noun phrase the compound is unrealistic “Ten-cow Jew” or some perturbation of these three words

as a name for a Jewish chief artisan in charge of decoration of the fortress. He also had a title,

in a third-person reference naming a title is expected, naming a personal name is out of place.

|

530 Vekony 2004b

531 Golden 1979. p. 173; Golden 1980. p. 252

532 DeGoeje 1893 1894, p. 120

533 Röna-Tas 1999a, p. 228

163

Third row: The second character from the right needs reconstruction: it was

N GH /ɣ/ or FORKED

E /a/, and therefore, the first word was Onagh N FORKED

E /a/, and therefore, the first word was Onagh N /onaɣ/ or

Ona Y /onaɣ/ or

Ona Y /ona/. /ona/.

The inscription contains much information: the writer was Ineg, the builder was Ud Didü On, the nation was Six-Savirs, and the fortress was the Mansion of Onagh Tegin. The inscription declared the Khazars’ supremacy of the region between the Don and Dnieper rivers, the land of the As people. It is noteworthy that the Mayaki Fortress was near the Don River; this geographical fact supports the exactness of the transcription.

7.2.10. Mayak Fortress smaller inscriptions

In 1909, N. E. Makarenko found short Rovas inscriptions in the Mayaki Fortress. They are dated to the period from the late 8th to the 9th centuries.535 The drawings of the

Khazar Rovas inscriptions were published by G.F. Turchaninov as well (Fig. 7.2.10-1,2,3,4,56).536 In the followings, the transcriptions are presented after each drawing.537

Figure 7.2.10-1: Drawing of the Khazar Rovas Inscription No. 1 of Mayak Fortress538

Table 7.2.10-1: Transcription of the Inscription No. I of Mayak Fortress

| Written with normalized Khazar Rovas font |

|

| IPA phonetic transcription |

|

|

Common Turkic (Khazar) transcription

(left-to-right) |

daðqajbin β... or daðqajbin k... |

| Translation from Common Turkic (Khazar) |

‘I will write w ...’ or ‘I will write k ...’ |

The left hand character can be OPEN V /(β/b-/ or OPEN V /(β/b-/ or FORKED K /k/ as well. This inscription shows typical features of the Khazar language: in the beginning of the word the changes /j/ > /d/ and

/z/ > /ð/ happened. However, the change /j/ > /d/ did not appear in every Khazar dialect; as it can be compared in the two versions of the name ‘Jewish’: /diðy/ in the

Mayak

Fortress Relic (Table 7.2.9-1) and /jyedi/ in the Alsöszentmihâlyfalva Relic (Table 7.2.14-1).

(Yedi, like Djuga, stands for Iudea. It is a common designation in Common

Türkic outside of the Caucasus) FORKED K /k/ as well. This inscription shows typical features of the Khazar language: in the beginning of the word the changes /j/ > /d/ and

/z/ > /ð/ happened. However, the change /j/ > /d/ did not appear in every Khazar dialect; as it can be compared in the two versions of the name ‘Jewish’: /diðy/ in the

Mayak

Fortress Relic (Table 7.2.9-1) and /jyedi/ in the Alsöszentmihâlyfalva Relic (Table 7.2.14-1).

(Yedi, like Djuga, stands for Iudea. It is a common designation in Common

Türkic outside of the Caucasus)

534 Vekony 2004a, pp. 221-222

535 Makarenko 1911, pp. 21-22, Fig. 19-22

536 Turchaninov 1964, pp. 75-76

537 Vekony 2004b

538 Vekony 2004b

539 Vekony 2004b

164

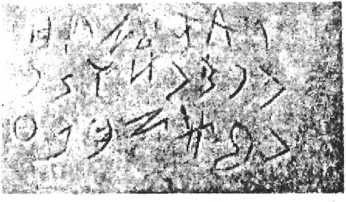

Figure 7.2.10-2: Drawing of the Khazar Rovas Inscription No. 2 of Mayak Fortress539

Table 7.2. JO-2: Transcription of the Inscription No. 2 of Mayak Fortress

| Written with normalized Khazar Rovas font |

|

| IPA phonetic transcription |

|

|

Common Turkic (Ogur) transcription

(left-to-right) |

bethisetrim |

| Translation from Ogur |

‘N. [member of a clan], I had it carved.’ |

The first two symbols of the inscription make up a tamga. Similarly, complex tamga symbols are known in other Rovas inscriptions, e.g. Needle Case of Jânoshida (Sec. 6.2.3).540 The glyph of the KR ARCHED I

/i/ is reversed in the inscription; however, mirroring glyphs is usual in KR. ARCHED I

/i/ is reversed in the inscription; however, mirroring glyphs is usual in KR.

There is a Common Turkic verb /beðiz/ meaning ‘carve’. The Ogur does not have the consonant /z/; hence it substituted

/z/ with /s/. Therefore, the inscription is in Ogur language and the word /beðiz/ was a Common Turkic loanword. The word /beðizet/ is a causative form; its meaning: to have it carved. The /beðizetrim/ means ‘I had it carved’. Since the

tamga means a clan-name, the meaning of the inscription is ‘N. [member of a clan], I had it carved’.

Tamga is a community property, and does not change as long as the clan exists, and long after

its dispersion. Tamga