97

“Kurgans with ditches”

In the Don steppes and even in the neighboring Voronej province and Kalmykia, the Khazars left much more

powerful traces of their existence. In the 650-700s appeared kurgans “with square ditches”, which

are believed to belong to the Khazar soldiers.

Female burials in such kurgans are a rarity, and that may indicate either Khazars sent to Don

only military units, or that unlike the soldiers, women were buried in flat graves, and they

are much harder to find. because practically they do not rise above the surface.

Anyway, the Khazar soldiers in the Lower Don are quite numerous, because by now were found about 300

such burials. Unlike the “Sivashians”, at the Don the Khazars erected individual kurgans for their dead. In

the center of the kurgan was located a rectangular grave (sometimes two) with a warrior and

his horse (or horse effigy, i.e. the head and legs with spread out hide and a harness). The horse

was usually placed at the entrance in the so-called “entry pit”, the rider was placed in a niche (“side chamber”), parallel to the horse.

These may be the warriors of the Khazar army, but unlikely ethnical Khazars, as is implied in

this discription because the discription depicts the ethnical burial tradition, not a political

affiliation. According to the visible traits, S.Pletneva stipulated for individual tribal categories:

| Trait |

Kipchaks

(Kimaks) |

Oguz |

Kangars

(Bechens) |

Bulgars |

Savirs |

“Khazar” |

| Inhumation |

X |

X |

Cremation opt. |

|

|

|

| Kurgan |

X |

X |

Small |

|

|

|

| Kurgan fill |

Stones |

Earthen |

Earthen |

|

|

|

| Secondary burials |

No |

No |

X |

|

|

|

| Fencing, ditch |

X |

No |

No |

|

|

|

| Entry chamber |

Not stated |

Not stated |

Not stated |

|

|

X |

| Balbals |

X |

X |

|

|

|

|

| Stella-image of deceased |

X |

No |

|

|

|

|

| Grave Cavity |

Ledge opt. |

Ledge opt. |

|

|

|

|

| Grave ceiling |

No |

X |

|

|

|

|

| Both sexes |

X |

No |

No |

|

|

|

| Head direction |

East |

West |

|

|

|

|

| Location of horse |

Next to |

Ceiling |

Next to |

|

|

Entry chamber |

| Alt. location of horse |

Ledge opt. |

Ledge |

|

|

|

|

| Horse carcass |

X |

X |

No |

|

|

|

| Horse effygy |

X |

X |

X |

|

|

|

| Severed horse lags |

At knee |

Not stated |

1st/2ns joint |

|

|

|

Without a concise description of the “Khazar” kurgans, and their cross-comparison with other

traits and attributions, even putative affiliation is impossible. What one calls “entry chamber”,

others call “ledge”, and others call “catacomb” (“podboi” in Russian-lingual reports), which the

Russian archeologists loved to identify with their favorite “Iranian-speaking” Alans. Go figure. |

Warrior was accompanied by military weapons, food, and mandatory zone a belt with numerous silver or

bronze buckles and plates. The belts' alloy buckle and plates were often ornamented in the form of a lotus or

vine shoots. The traditions of Central Asian and Byzantine art may have influenced the formation of this style. The material of

the cast belt decoration, the character and splendor of the ornament

probably could testify not only about the wealth of the warrior, but also of his status.

98

Of the armaments, in the burials with “ditches” most often are found remains of a so-called Hun-type

bow, more precisely, of its Bulgarian-Khazar or Saltov versions. The wooden core of the bow was

augmented with

several bone plates (usually of deer antler), they gave greater stiffness, and made bow more

rebounding. The wood of the core almost always decayed in the burials, but the surviving bone plates

allow to see the main structural features.

Often the iron arrowheads are found in the burials, long-range three-bladed light or heavier “armor-piercing”,

“bullet-type”, as they are called by the archeologists, these could pierce a shield, armor, or chainmail.

Besides bows, into the graves almost always deposited a knife or even a few of them, and sometimes

battle daggers. Other

weaponry is rare. Occasionally are found remnants of long blade weapons (sword, broadsword, saber).

That was a time when a more light and comfortable to handle saber was replacing heavy swords and

broadswords. Sometimes graves contained iron or bone bludgeons.

Judging by the bows almost always placed in the grave, at that time they were the main weapon

of the nomadic Khazars. Bladed weapons are rare, but this is also explained by the unaffordable

luxury of such expensive piece. For the same reason in the Khazar

burials are rare chain mail armor and corselets. At the same time, the bow is always somehow

individual, “adjusted” for its owner,

and at the same time relatively short-lived, unlikely to be passed as inheritance.

| These fluke speculations demonstrate an unfamiliarity with the studied subject. Due to Ibn

Fadlan descriptions, some archeologists cought up with the idea that Tengrian grave inventory is not

a sacrifice, as was reported for centuries, but an assortment of travel necessities that not only

mirrors the necessities that a diseased used during his lifetime, but largely consist of these

necessities. To deny a dead father his chain mail armor because of its price is unconceivable, for a

number of reasons, not a least of which is that after his death a parent continues to assist his children. Or he could travel light, or the armor was not his but the state's or furnished for the

battle, or a loan, etc. The tradition of armory was not invented in Venice, and without that

tradition the continental-wide conquests of the Eastern and Western Huns, Türks, and Mongols would be impossible. |

Interestingly, even in the rich burials next to the luxury gold and silver imports usually were

very rude and simple handmade vessels, probably it was some ritual.260 Most

likely, such vessels were made especially for the funerals. Sometimes next to the deceased lay dice cubes, probably

among Khazars dice games were popular. Another common find in these kurgans are Byzantine gold

solidi. Often they have holes or loops for wearing them.261

99

Around the grave was dug an encircling ditch as more or less right square. Same typr of a trench could

also encircle the special ritual place without burial.262 The width of the trench

does not exceed

one or one and a half meter, and usually it even less. The depth did not exceed the width (naturally

these are only the traces of the trench in the continent, that is in the clay under the humus layer). In

the ditches sometimes are found bones of sacrificial animals.263

The authors of this book had a chance to participate in the excavations of four such kurgans

containing five graves, one of which was not robbed. This has already been discussed in

detail in the preface.

The

“kurgans with ditches” remind the Türkic burial and memorial structures of the Central

Asian nomads. The similarity is in the fence-trenches, and in the construction of the grave pit (so-called “pit with

niche”,

i.e. with a shallow niche), and in the mandatory horse that ias laid together with

the deseased.

| These are not just ambiguous Central Asian nomads, whose cemeteries had dozens of local

distinctions, these are specifically the Kipchak-type burials, widely described in archeological and

laymen literature. |

From the Bulgarian nomadic burials the Khazar kurgans differ by the construction of the grave pit, and

by the presence of

the trench, and the position of the horse (Bulgars laid it on top of the rider), and by the

construction of the laid in the graves composite bows with bone plates.264 And

that is the evidence

that Hunno- Bulgars were replaced in Lower Don steppes by nomadic Türks: the Khazars-Türkuts, or

rather the soldiers that may belonged to the Türkic elite of the Khazar Kaganate. Their ethnicity is

also evidenced by the Türkic runes incised on the coins and bone plates of the bows. This is also

evidenced by the gold coins found in the burials, the

traces of the Byzantine payments to the Khazars, described by the Byzantine chronicles.

| The authors use a figmentary term “Türkuts” to designate the Türkic Kaganate, first suggested by

L.Gumilev to discriminate between different Türkic people and states. The figmentary term does not

carry an ethnic meaning, and is a form of non-statement. That the Bulgars (and Maguars, and Khazars,

etc.) were numerously attacked is well-known. In 550s these were Avars, or Uars, or Varchinits, or

Uar-Huns; in 550s they were attacked by the forces of the Türkic Kaganate, who divided Bulgars into

Avar Bulgars and Türkic Kaganate Bulgars; in 650s they were attacked by the Khazars and their Oguz

allies; in 750s they were attacked by the Kangar-led tribes known as Bechens, Bajanaks, Bosnyaks,

Patzinaks, Pechenegs, etc.; after 750s they were attacked by the Oguz tribes. To throw all these

forces into a single basket and call it with a fictitious name “Türkuts” is a poetry, not a history. |

100

Khazars constructed their

“kurgans with ditches” till the beginning of the 9th c., but then

something happened in the Lower Don steppes. Archaeologists agree that in the first third of that

century (800-830), “kurgans with ditches” disappear. The cause is unknown,

as is not clear at all what happened

with this militant group of nomads. Were they destroyed? Migrated to new lands? Went to the next

distant raid and did not come back? This is a paradox repeatedly and not without irony noted

by the archaeologists: the nomads, in which many recognize the Khazars proper of the Kaganate heyday,

at the peak of their power for no apparent reason disappear somewhere

without a trace. But

after their disappearance from the pages of the archaeological record, the Khazar Kaganate endured for about

another two hundred

years...

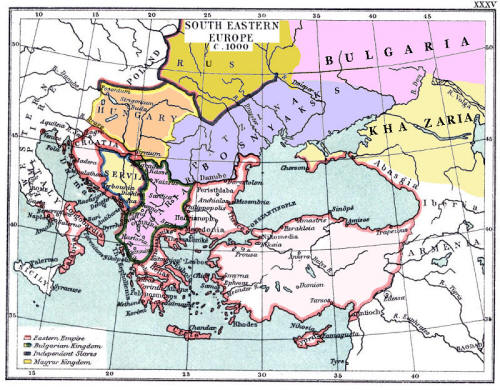

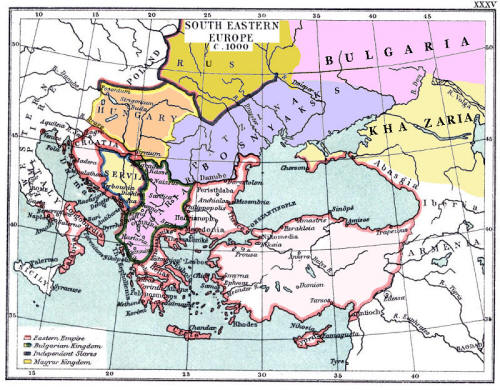

A single look at the map would help the august puzzlement.

| 630-660 |

660-750 |

750-1055 |

|

|

|

|

|

| Kangars-Bechens 850 |

SE Europe 1000 |

Putative Khazaria 650-850 |

|

|

|

|

|

We see the unsung Kurgan waves. In the 650s the “Great Bulgaria” fell under a joint attack

of Khazars and their Horezmian mercenaries, and Kangar Union under pressure from the Türkic Kaganate

expanded to reach Khazars Kaganate; in the 750s the Kangar Union had to move westward to make room

for the Oguzes of the Oguz Yabgu state, Bulgars fell its first victim, and in the Lower Don steppes

appeared the first “kurgans with ditches”, apparently belonging to the Kangar allies and relatives

Bechens, i.e. Kipchaks in a matrimonial union with the Kangar tribes. Then at about 800-830 the Oguz

tribes displaced Kangars from the Don-Itil interfluvial, and the Kangars-Bechens moved to Atel-kuzu,

pressing on the Bulgar Kubars and their marital partners Magyars. The “kurgans with ditches” moved

to the right bank of the Dniper, only to be supplanted in the 990s on by the new Kipchak “kurgans

with ditches”.It is clear that under the “Khazars” umbrella, the old polities of the Bulgars,

Suvars, and Huns continued their existence, and the new polities of the Kangars-Bechens and Oguzes

had formed. The Khazars proper probably constituted less than 5% of the state population, and their

graves concentrated in their traditional cemeteries in the Khazar domain defined by S.Pletneva.

|

There is a not unfounded version that these people were defeated in the civil war that broke out among

the Khazars, and those who survived retreated west.

| That is the allusion to the Kubar revolt, and their fleeing with their Magyar allies to the

Atel-kuzu. The theory implies a Khazar pressure to convert to Judaism, a highly unlikely scenario

given the absence of such pressure on all other constituents of the Kaganate, the nominal power that

the Khazars wielded over their diverse subjects, and their religious tolerance numerously mentioned

by the authors. In Azeri, kübar means noble, magnate, aristocrat, grandee, elite, i.e.

in our case Kubar is a princely tribe, or a tribe headed by a prince. Kubars are also associated

with Suvars, as a dialectal variation, and then Kubars are ethnically a tribe of Suvars. Another

indication is that Kubars controlled the area north of the Crimea, and then Lebedia laid in the

Kubar domains. That would explain their flight together with Ugrs (Magyars) from the ravage by

Becheneks. No revolt, no religious persecution, but a standard defense by escaping. |

102

|