Sumerian or Sumer language is the most ancient cultured language of the world. About

a thousand years before Christ it no longer existed, but the news about it in its literature, consisting of

cuneiform writing, dates back to over 4,500 BC. During the 3500 years of its existence, the language from

the first start when Sumerians invented their

writing system gradually evolved and reached a considerable height of which we received news only through

studies and reading cuneiform inscriptions on rocks in the ruins of Babylon and other neighboring

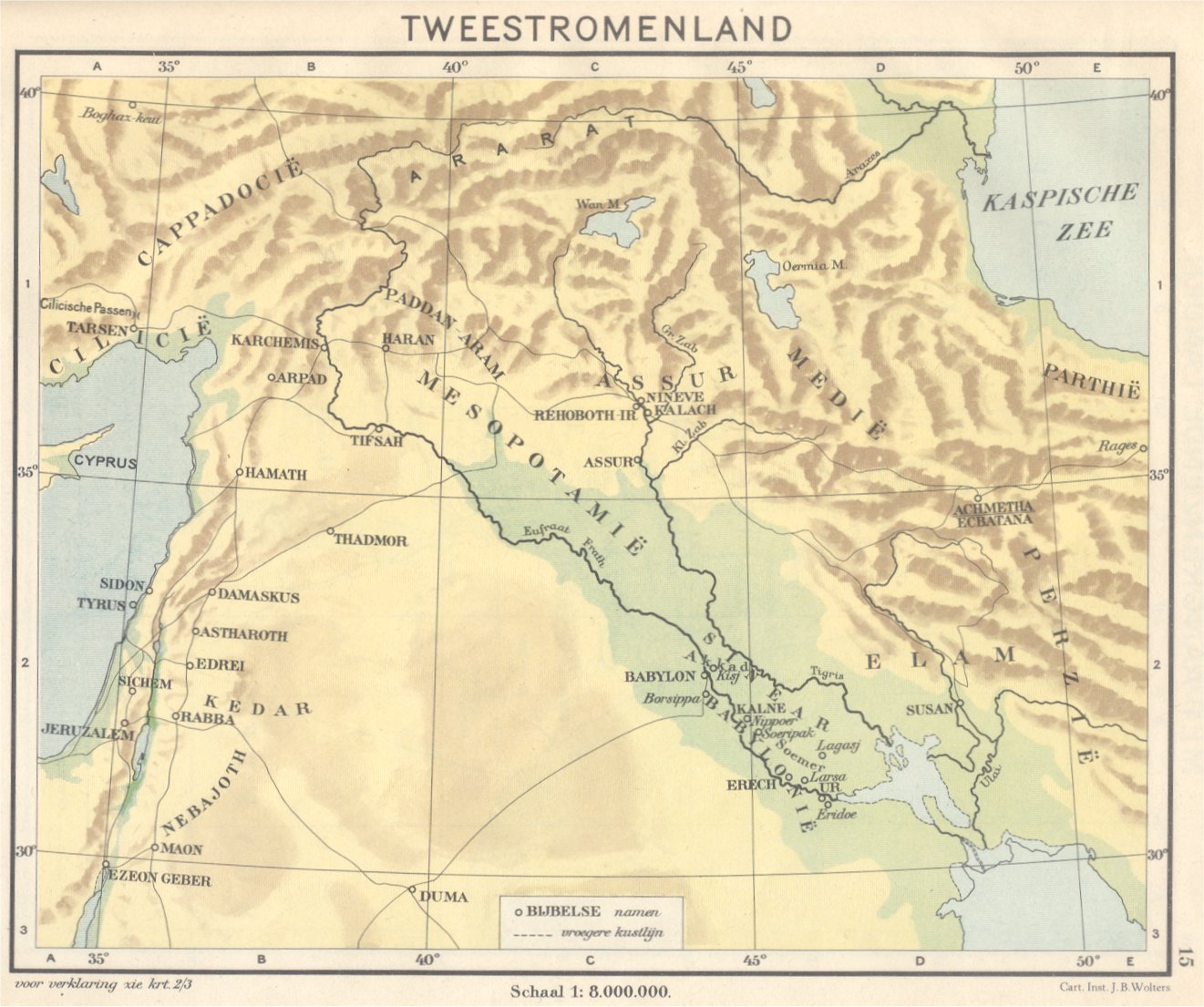

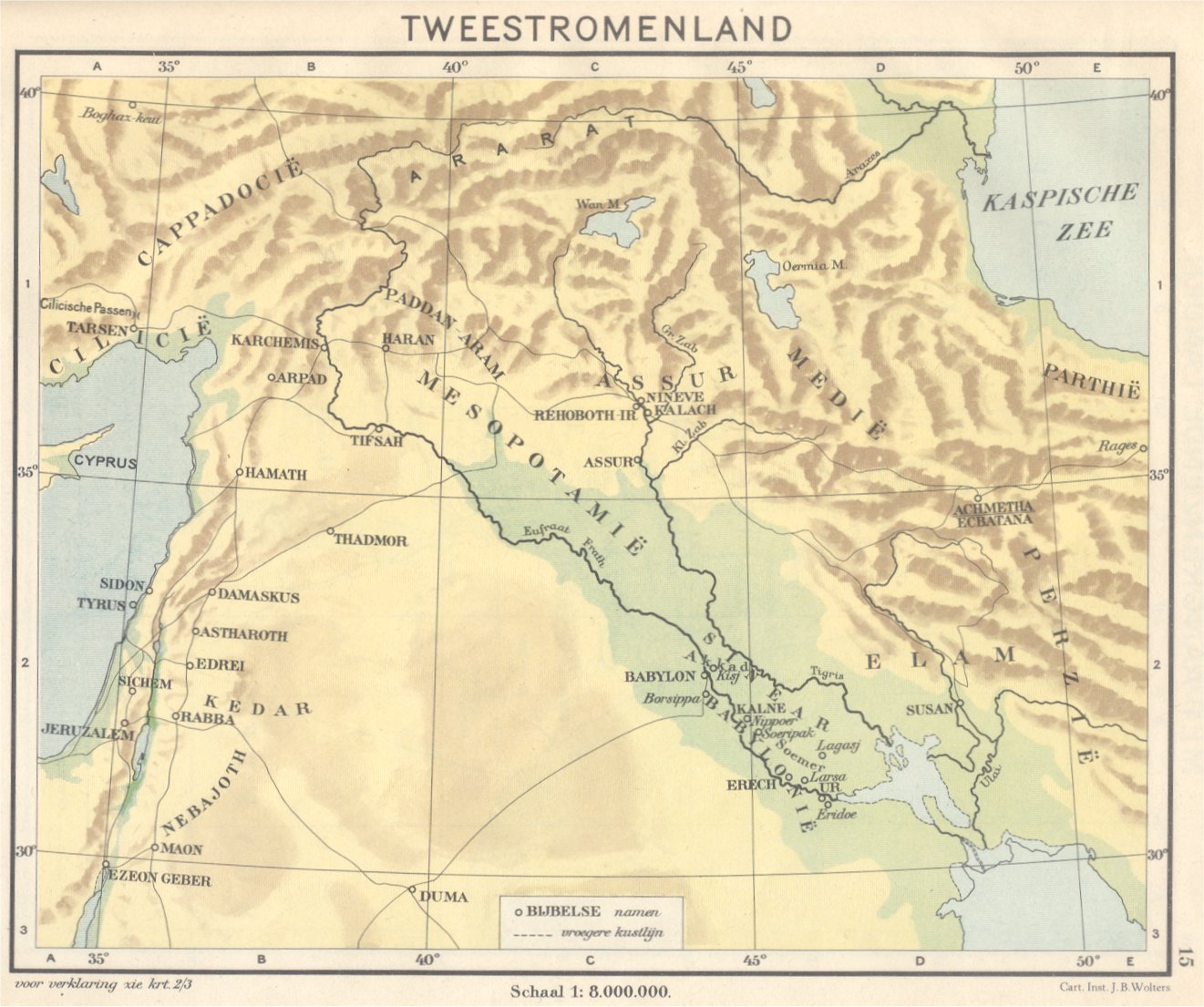

cities. Homeland of the Sumerians was in the Sinear land, namely

in the area of the rivers Euphrates and Tigris. Sumer language was divided in two vernaculars,

the Sumer proper in the south and the northern (Semitic) Akkadian in the northern part. The southern dialect was cleaner than the northern, but both comprised one Sumer language (Yeah,

Walloon and Flemish also comprise a single Belgian language).

Sinear land

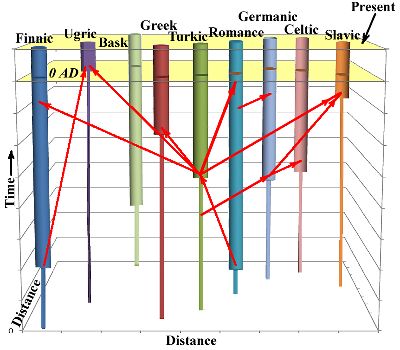

Then a question became interesting, which tribe the Sumer people belonged to according to

its language. The French scientist Oppert and an English expert on cuneiform writing Rawlinson were of the opinion that the

Sumer language by origin belongs to the Ural-Altaic languages. They were joined by Finnish scientist Yrjo Koskinen. Then a

French scientist Lenormant, a great connoisseur of the cuneiform writing, was of the same

opinion that exactly Sumerians, according to their language, were the people of the Ural-Altaic,

or more precisely even Ugro-Fennic origin. He was joined by English scientists Smith and Sayce, well engaged in reading

of the cuneiform writing and Ugric-Altaic languages.

They were followed by German scientists Onken and Hommel and a large number of other

German and French researchers.

But against this affinity of the Ugric-Altaic languages

with Sumerian language argued few scientists, and mainly three, namely French scientist Halevy, a

German expert on Sumer language Paul Haupt and a docent of Sanskrit language Helsingfors

(Helsinki) Donner. But

it should be stated that Halevy and Haupt barely or not at all studied the Finno-Ugric languages,

and Donner, who has written several good works on the Finno-Ugric comparative linguistics, I think

deliberately ignores many akin /448/ motifs and elements. Of the other opponents of the

Sumer language affinity with the Ugric-Altaic I do not want to talk, because due to their ignorance of the Finno-Ugric

languages, they are irrelevant. The best experts in the Finno-Ugric languages are Finnish scientists Castrén and Ahlqvist had no occasion to express their opinion against or in favor, but the nature of their philological studies can rank them with the first group, in favor of affinity of the Sumer language with the Finno-Ugric languages.

Let us turn now to the comparison of the languages under consideration.

To establish an affinity of one language with another or others, we

should find similar, alike, or identical forms 1) in phonetics, 2) in etymology, 3) in lexicography,

and 4) in syntax — in all compared languages.

In respect to the phonetics of the Sumer language

should be stated that the whole of its sound structure has a simple,

transparent nature unique for the all Ugro-Altaic languages. The property of the language is such

that every word in the beginning has only one consonant sound - following most of the Ugric-Altaic

languages, that avoid complex sounds ch, sch, ts, etc. at the beginning of the words. In the middle of

the words a consonant follows a vowel and vowel follows a consonant as in the Finno-Ugric languages, and

the diphthongs or complex consonants are few. For the most part the words

only have one syllable, rarely two, very rare three syllables.

One of the main centerpieces of the Ugric-Altaic languages is the so-called vocal harmony

(vowel harmony) or similarity of the vowel sounds within one

non-complex word. This important grammatical law classifies that vowels

are divided into three parts: 1) hard a, o, u, 2) soft ä, ö, ü, and ə, and neutral (middle) e, i.

This law of vocal harmony - although the language evidently has other sounds for the words - in

fact comprises the same phonetic phenomenon that we find in the above Ugric-Altaic languages, and just for that reason

every expert should attribute Sumer language to the Ugric-Altaic group. In particular, so has done the French

researcher Lenormant, for which he had a full right to do. This aspect must be a most dicisive when

we know that the law of vocal harmony exists only in the Ugric-Altaic languages, and it is totally

absent in the European-Aryan languages.

In respect to the etymology, first should be noted that

the Sumer language does not have grammatical gender of the words, i.e. it does not have words of male and female and neutral gender,

as e.g. have almost all languages of the European-Aryan origin. Like all Semitic languages, the ancient Assyrian language had

words of male and female gender, therefore it very much differed from the Sumer

language, from which it borrowed many words. As is known, all languages of the Ugric-Altaiic

peoples without exceptions have no words with grammatical gender. In that is one of the main traits

of their affinity with each other, as well as with the Sumerian language. All languages of the

Ugric-Altaic peoples, like the Sumerian, denote the natural male and female sex with special individual

words that grammar-wise do not carry in themselves neither male, nor female, nor neutral gender.

As to the individual words, it should be stated that the lexical-graphical side of the Sumer language

has not been enough studied and processed. We just do not know all Sumerian words comprising the vast literature of

the cuneiform rock writing in the ruins of the oriental cities. It is possible to hope that their

quantity will increase in the future. But a number of those words which /449/ so far became known,

and which comprise the read Sumerian texts, correspond in substance and meaning to the similar words

in the Ugric-Altaic languages. The number is not very large, but related to the number of the total

known lexical stock, it is sufficient for comparison. It constitutes lexicographical material for

lexicographical comparison of the Sumer language with other Ugric-Altaic languages.

In the following presentation I will cite a few words:

In Sumerian ad or adda “father”, in

Median atu, adda, in Est (Estonian) att, ata or ätt, in

Finnish ati “father-in-law”, in Magyar atya “father”. in Ostyak ata, in Vogul

aze , in Votyak ataj, in Mordovian ata “old man”, in Cheremis

(Mari) aĉі, ati, ata. Apparently, this root has also passed to the Aryan-European languages, for example in Greek ά: τα, in Russian ot- ets. Sumerians also had

a God Atar, “father” of the light.

In Sumerian nene “woman, virgin”, in

Est (Estonian) neid, neiu, neitji “maiden” in Finnish

neito, neiti, neitsyt, in Lapar (Sami, Lapp) nieid, neit, neita, in Magyar ne,

in Manchur neinei, in Chinese niu, in Zyryan nil. From the same root comes the Finnish nainen “wife”, in Votyak

and Veps naine, in Est (Estonian)

naene or naine, in Livonian nai, in Magyar nö.

(English nanny, nana; French norrice; Latin nutricius “wet-nurse”; Greek nanna “aunt”. “Nutrition” and

“nurse” also are derivatives of a form of nanny. All “IE” forms are spotty and without credible

etymology).

In Sumerian an “sky”, anna, annab “God, Goddess” or “father, mother”,

in Median annap, in Turkish and Tatar ana “mother”, in Magyar anya “mother”, in Votyak

ana, anaі, in Ostyak angi, in Lapp (Sami) aedne, in Votyak ene, in Tungus änä “mother”, in Est (Estonian) (Fellin

dialect) änn “mother”.

In Sumerian akku “big”, in Median ukku, in Finnish ukko “grandpa, old man”, and a

mythological deity, in Est (Estonian) ukku, uku, in Veps uk

(Türkic aga “senior, elder”became a true international word in the Eurasia).

In Sum. tur “son, baby”, and also “boss, chief”, in Median tar, in Est (Estonian)

(Verro vernacular) tsura “young man”, in Magyar gyermck “baby”, in Mordvinian tsur “son”, in Turkish (eastern

vernacular) tura “royal court, chief”. (English tower with numerous

cognates in "IE" languages and numerous derivatives, all forms are spotty and without credible

etymology; in addition English has a synonymic “castle” from the same source and with dubious “IE”

etymology. Russian also has “tura” as tower).

In Sum. erim, eriv, eri “slave, servant”, in Est (Estonian)

orі, in Finnish orja, in Livonian verg. Another form of the Sumer word

“servant” eru, uru, ur, in the Magyar ur “lord”. According to Yrjö-Koskinen, the

Aryan-European root is in Sanskrit ayrja, in Germ. Ehre, in French air of the

same origin. The Magyar word ur is found in in Finnish lang. uros, in Zyr. veres or

verös, and in the Lithuanian vyras, in

Latvian virs, and in Latin vіr. According to Koskinen, Sumerians were taking Aryans as servants,

and thus so different concepts converge in one word.

To cite Yrjö-Koskinen tongue-in-cheek idea of Finns employing Arians as servants

is hilarious, he clowned the self-admiring “Aryan” spirit of his days. Closer to home is the example

of the guest vs host, both derivatives of the Türkic göster (n., v., adj., adv.), stem

of göstermek = to demonstrate, which developed and was borrowed with bifurcated

semantics natural for agglutinative languages but alien for the receiver languages. With

agglutinated affixes, the stem produces both active and passive verbs, nouns, and adjectives, akin

to “demonstrator” and “demonstrated”. The Türkic ar/er/ir “man”, like Sumerian er,

and like göster, can produce active and passive semantics, creating bifurcated meanings. That

bifurcated meaning is retained in English, e.g. “he is the man” means that he is a hub point, a

chief, and “my man does it” means that he is a subordinate. This bifurcation can be expanded to any

situation: “boss”, “enlisted troops”, “serfs”, etc.

Since, unbeknown to Yrjö-Koskinen and

his cohorts, the Indo-Iranian “Aryans” migrated to the Iranian Plateau and Indian subcontinent at

about 1500 BC, Sumerians did not have a chance to employ the “Aryan” men in either master, nor a

servant capacity. The etymology comes from a different time, different language, and different life. |

In Sum., in Akkadian gu or ge “night”, in Fin. yö, in Est

(Estonian) öö, in Mordvinian ѵe, in Cheremis

(Mari) jut,

in Votyak üі, in Zyryan ѵoі, in Lapar (Sami, Lapp)

igja, in Ostyak at, in Vogul i and edi, in Magyar ej,

ejszaka (ejsaka), in Turkish gedsche.

In Sum. ar “country of the world”, in Magyar or-szag (or-sag) “country, land”,

in Est (Estonian) kaar, in Finnish. kaari.

Some Sumer language words can be found common with other languages, for example in

Sum. gala “great” in Est (Estonian) Kole “scary, huge”

(Türkic Ogur gulu, Oguz ulu/ulug); in Sum. sagig

“crazy” in Ostyak jōgedus, by Fin. jokeus (Türkic qal); in Sum. kal “hearty, touched”, in Estonian hale; Sum. jaga or sada, in Ostyak suda, in Finnish jydan

(Türkic köŋül/küŋül/kögül, köŋüldaki/köŋültäk); in Sum. іla “through”, in Est

(Estonian) ule (Türkic üzä); in Sum. meni “поди”

(?), in

Estonian mine; in Sum. ena or enu “master”, in Est (Estonian) onu

“uncle” (meaning “guest, master” “kula, onu”) (Türkic idä/idi);

dingir “god”, in Turkish tengri; in Sum. nzu “meat”

(an apparent typo, in lieu of “uzu”), in Magyar hus; in Sum. til

“full”, in Magyar tele (Türkic tolï/tolu); in Sum.

pal “sword”, in Magyar pallos; in Sum. mar /450/ “road”, in Magyar mor; in Sum. ar

“nose ”, in Magyar orr; in Sum. nab “light ”, in Magyar nap “day”,

in Sum. sal “vulva”, in Magyar szül (sül) “give birth”, in Sum. ud “sun”, in Mongolian ud;

in Sum. e “house”, in Turkish eѵ; in Sum. gallies “expensive”, in Est (Estonian) and Fin. kallis.

The Sumer language personal pronouns without a doubt have the same basis that exist in almost

all the Ugric-Altaic languages. But the same foundation or elements are also found in the European-Aryan languages, and therefore some scholars like Halevy and Donner, argue that

these elements are not only Ugric-Altaic and can't not serve as proof of the affinity between the

Sumerian and Ugric-Altaic language. It is undeniable that in fact in some Aryan-European languages are

pronouns of such elements. But this is not an evidence against the affinity of the Sumer

language with the Ugric-Altaic. The Sumer language existed before all known languages as the

language of culture, it had an influence on the Aryan-European languages also, but it did remain the

Ugric-Altaic language. Its nature belongs to that kind. Therefore, its pronouns are closer to the Ugric-Altaic than

to the Aryan-European languages.

Even more than that simple comparison the affinity of the Sumer

language with the Ugric-Altaic is proven by the attachment method of the possessive suffixes to the roots of the nouns. This method is the same that for example exists in the Fennic and Magyar languages, although in the phonetic

composition the suffixes seem to be different. So for example in Sumerian adda-mu “my father”, in Finnish isa-ni, in

the Magyar atya-m (Türkic atta-m); in Sum. adda-su “your father”, in Finnish.

isa-si, in Magyar atya-d (Türkic atta-g); in Sum. adda-na “his father”,

in Finnish sa-nsa, in Magyar aty-ja (Türkic atta-i); no-Sum.

adda-me “our father”, in Finnish isa-mmo, in Magyar atya-nk (Türkic atta-maz) and

so on. This method of connecting possessive suffixes, and the corresponding possessive suffixes, does not exist in the

Aryan-European languages, which confirms the view of Loporman, who has not completely noted this property.

Browsing through the forms of the numerals, we have to recognize that their resemblance is

striking. As is known, the names of the numerals play a major role in establishing affinity between languages.

We do not have sufficient material to compare syntax. The Sumerian compound

forms, for example, tursal, literally “child-daughter”, i.e., a maiden, in Est. (Estonian)

tutarlaps, in Manchurian sargan-jui; Sumerian si-me, literally “eyes water”, i.e., tears, in Est

(Estonian) silma-wesi, in Manchurian yasa-i-muke, etc. prove the certain the affinity of the Sumer language to the Ugric-Altaic languages.

In conclusion of all the observed materials for explanation of the relationship between the Sumerian

and the Ugric-Altaic languages, I am coming to the view that the Sumerian language is kindred with the Ugric-Altaic

languages, and that the Sumer people by their origin are close to the peoples of the Mongol-Fennic tribe.

We'd get even more evidence of this affinity when the cuneiform literature will be studied more thoroughly

on the vocabulary and forms. But even what we know so far is quite enough to have an affirmative opinion

on this affinity. The entire laws of language that correspond to the similar laws of other languages, can

not be accidental. The Ugric-Altaic languages, and especially the Finno-Ugric languages have a great-grandfather, or

at least an elder brother in the Sumer language.