|

|

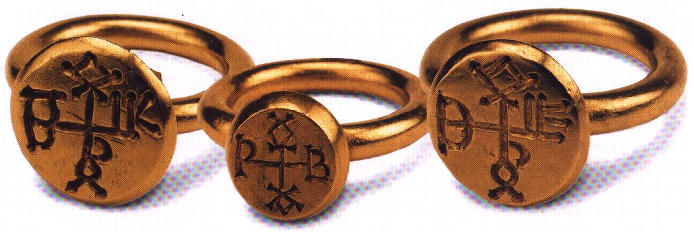

Kurbat signet ringAzgar Mukhamadiev |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kyzlasov Alphabet Table | Amanjolov Alphabet Table | Muhamadiev Alphabet Table | Book Content | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Introduction |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Azgar Mukhamadiev is an outstanding numismatist who dedicated his life to study of Eastern European and Middle Asian coins and inscriptions.

The citation below is from his latest book, and like his previous works it is filled to the rim with insights and scientific breakthroughs.

In particular, the question of Kurbat burial rings was deemed to be resolved by eminent Byzantists with a clear-cut conclusion: the

monograms are in Greek, though not the Greek that every Greek or Cyrillic Greek-literate person can freely read, but in a some kind of

unreadable Greek accessible only to the initiated few. A. Mukhamadiev examines the artifacts anew, and comes to a contrasting conclusion: the monograms are written in a

Türkic alphabet that geographically was in use from Middle Asia to Eastern and Central Europe, and in Türkic language. Thus, instead of being a 2 out of 3 Greek enigma, the seal rings of the Kurbat's burial treasure is a step forward toward understanding the history and development of the Türkic alphabet and the Türkic history in general.

Kurbat/Kubrat puzzle: it was suspected that Kubrat is a Greek distortion of the Türkic name Kurbat. Etymologically, Kurbat is more suitable for a Türkic name, and it has plenty of analogies with Chur/Kur = prince, leader, head, and Bat/Batya/Bata = father, senior, superior, while the etymologies for Kubrat are suspicious by their lowly semantics unbecoming for a king, especially so when traditionally a person could change his name at will, and during a lifetime may have changed a number of names, without any need to live with something unbecoming or lowly. But... facts are self-imposing, and if Kurbat's ring says ”Kubrat”, then Kubrat was his chosen name, and it is rightfully used by the author. Buddhism: A. Mukhamadiev's study of Türkic inscriptions led him to a discovery that the religious convictions of the population were not uniform: in addition to Tengrianism, hard evidence shows a spread of Buddhism and/or Hinduism among the constituents of the Hunno-Bulgarian tribes. Though the underlying beliefs in afterlife and incarnation were common to Tengrianism and Buddhism, the respective religious rituals differed, and the result must have been a symbiotic blend, with uneven mixes, and uneven utilization in everyday life. The literary evidence mentions only Tengrianism. Administrative division reflected in the ethnic names. This discovery is another enlightening breakthrough in understanding the Türkic history, which, when accepted, is going to throw away plenty of unwitting speculations, some very old and traditional, and some very new and imaginative. This insight is a step forward toward understanding the history of Antique period in the N.Pontic. No wonder that Kuturgurs are known in the West ”to locate, to relocate, to settle, or to occupy” the west, it is a western ulus of the state. In contrast, the ”Onogurs” is an alliance of ten tribes, without a reference to their location, but since it gave a name to the Greek Phanagoria/Onoguria, in the 5th c. BC their union already existed along the Black Sea coast. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Chapter 1 Antiquity and Early Middle Ages Sect 4. Inscriptions on engraved gold rings from treasures of Khan Kubrat (script of early Bulgars) |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

48 When one of my friends, an organizer of Hermitage exhibition in Kazan, presented me with a book of ”Khan Kubrat Treasure” (St Petersburg, 1997), and I browsed it, my attention was attracted by inscriptions on the rings, shown in the catalogue, with letters that seemed familiar, and identical to some letters in the inscriptions on early Middle Age bowls from the Itil region, and I asked about them. He responded with indifferent tone and without allowing any objections that they already had been read. However some oversights in the book, and also negligence were evident, and raised very clear doubts both in reading, and in the conclusion about the inscriptions to be ”Greek” monograms. For example Kubrat, who was living in the 7th century, is called by the Mongolian title ”Khan”, which appeared six centuries later, in the 13th century 2 (A. Mukhamadiev repeats a popular PC Russian claim, designed to deny presence of Türkic people in Europe before the Mongolian conquest. In fact, Kurbat's son Asparukh and his progeny are documented to have been called Khans, some six hundred years before its claimed Mongolian introduction. The title Kan/Kagan/Khakan/Han/Qan/Chan(ui) precedes Kurbat by roughly a millennium - Translator's Note), and Kubrat in a schematic sketch is depicted as an imbecile plumed with gold ornaments and a saber in gilded sheaths. All this was not impressive, and we already went through it. The old timers probably remember that during Soviet times on the second floor of the Kazan Ethnographical Museum hung a huge portrait of a man with purulent bulging eyes and half-open mouth with dripping saliva. On a portrait was obviously depicted a sick man with congenital dementia, but a sign next to the picture, attached on the wall, had a ”Tatar” legend a giant font.

48 In the catalog descriptions some authors routinely label the treasure's vessels and ornaments made of precious metals as Iranian, Byzantian or at best a Sogdian manufacture. A question arises: what, in their opinion, the Türks-imbeciles could not make these art objects from gold and silver? We can say that we also already went through this. In the beginning of the 60es of the last century I, being a student, participated in excavation of the Kipchak Khanate capital Sarai al-Djedid, located in the Lower Itil region. Any gilded object of a minimal value found in the excavation, or an artistic fragment different from the usual red clay (by the way, finely fired) of the ”Tatar” ceramics, were reported as products of Iranian or Arabic origin. Because I, since my childhood, had a ”fine” hand inherited from my maternal grandmother, herself an artist of all trades, I asked our (Kazan) excavation head: ”What, could not they themselves had made these objects?”. And he, a generally kind man inside, exclaimed in his simplicity: ”Whom, them? But these are the Tatars?!”. But in the following years, being a chief of the excavations, I happened to dig out fine objects of similar character. Especially interesting were discarded objects from a basement brick shop in the Sarai al-Mahrusa, which pointed that they were made in this shop. The multi-year excavations with multiple finds testified that the city culture in Itil area, which developed during the Khazarian period in the 8th century (the last Khazarian city Saksin in the Itil area was taken by Mongols), did not fade away. The Türko-Tatar craftsmen were masters of their art, and disrespect for them is an obvious or hidden snobbery, remaining from the Soviet ideological period, and totally inappropriate at present. Amazingly, it is a fact: scattered worldwide, are in existence hundreds of vessels made from precious metals, which were found in the Itil and Ural region. Around the rim of some of them are long enough inscriptions, sometimes 15-20 words. Just the Hermitage has quite a few exemplars. And not a single scientist had an idea donned on his head to connect these inscriptions with the history of civilization in the Itil region, where the Huns, pursued by the Chinese armies (i.e. defeated by Chinese armies and pursued by Tungus Xianbi/Hsiem-pi/Syanbinians, who took control of all territories of the Hunnish Kaganate, and absorbed over 100,000 Hun's families, creating a Tunguso-Türkic language nowdays known as Mongolian), broke through to the Itil and in the beginning of our era created a state1, in which economy, documented by archeological research, in addition to advanced metallurgy, for the first time in Eastern Europe an important place held not only the monetary circulation, but also production of their own numerous coins in the form of bronze ingots with standard form and exactly determined weight. The known archeologists O.N.Bader and A.P.Smirnov, correlating the areas where vessels made of precious metals were found, with their discovery of ”settlements, fortresses and burials”, came to a conclusion that they ”testify to the existence in the 1st millennium of our era in that area of an economically strong center, able to accumulate great quantity of precious imported objects” 2. The history of the Itil and

Ural region is complex and multilayered. In the 6th century, after Istemi Kagan, allied with a shah

of Iran (Chosroes/Khusrau ”Anushirvan”, ”the Blessed”, 531-579), crushed Ephtalites

(in 565) in the north of

the Turkestan, a part of the Ephtalites had to retreat to

the Middle Itil region. Judging by the

contents of inscriptions on some vessels, with these events was linked a penetration of

Buddhism. Therefore is not unexpected and not

by chance that in that region started an early construction

of the cities, eventually came about the capitals of five states, including

capitals of

such world empires of the early and late Middle

Ages as Khazaria and Kipchak Khanate. The numerous finds of vessels from Itil and Ural region, all without exception, by their appearance (without consideration of the contents of the inscriptions, and ignoring the medieval history of the Itil and Ural region) are assumed to be the art of Sassanid, Sogdian or Indian origin. Such findings, performed with aplomb grounded on disrespect to the early Middle Age history of the Itil region, frequently resemble fortunetellers' palm reading. Some researchers, although, believe that inscriptions denote a weight of a vessel, and probably therefore the inscriptions are discounted as not having a meaningful value for detecting their origin. Without excluding such a possibility, a questions could be nevertheless raised: why the inscriptions carry not Persian, Indian (for example, bowls with image of Vishnu at the bottom) or, with rare exception, Sogdian character, but are written with Chorasmian (aka Kwaresmian) letters? Does it indicate that the vessels from precious metals were weighed only by the trading people of Chorasm (aka Khoresm)? The Russian orientalists of the 19th century were experts, competent enough in the area of not only history, but also in linguistics. During the Soviet period, in contrast, a historian studying history of Khazars, Bulgars or Kipchak Khanate, can be compared with a scientist who, without knowing Russian, would profusely discuss a, say, Norman origin of such old Slavic tribes as Drevlyans (”Foresters”) or Polyans (”Fieldsmen”). Such researchers, who had written tons about the art, about the origin of the Bulgars or Tatars, considered below their station to know the language or literary monuments of the Bulgarian and Kipchak Khanate periods. In the turbulent period of forming the Khazarian Kaganate, judging by the shared religious and written culture, the Bulgarian tribes of Kubrat (at least their major part) had to leave for some time the Middle Itil region. The Khazarian Kagan Joseph in a later letter, written after 960es, mentioning the constituent tribes (including the Bulgars along Itil) of the Kaganate, emphasized: ”Each of clans has a known (hereditary) possession (received) from their ancestors”. By the way, the map of the Arabian geographer of the 12th century Idrisi indicates the location of the ”remaining Bulgars” northeast from the city of Bulgar. Before turning to the inscriptions on the rings

from the Kubrat treasure, note that are known similar objects with inscriptions, found in

ancient Hunno-Türkic

burials. For example, excavations of

the 1963 Astrakhan archeological expedition, organized

by V.P.Shilov, found a man's skeleton at a depth of 1,85 m in one of the kurgans on the Orda mound near Zaymishche

stan in the Chernoyar district. Next to him were a skull and lower

parts of a horse legs, a bone battle ball, a clay jug in

pear-shaped form with the iron knife inside,

and other objects, and in the left hand was a gold Abbasid dinar dated 143

of Hijra (760-761). The coin was studied by a Petersburg orientalist A.A.Bykov, known

for his punctuality and objectivity. The dinar, as scientist noted, would be a usual coin if was

missed a clearly visible graffiti on the back above a top line of the

central legend, which he

presumed was probably a property sign of the

deceased. However, as is apparent from the graffiti, it was not

a simple sign or tamga, but two signs resembling runic letters:

These signs later attracted a close

attention of the author, when in a burial of the Hunno-Sarmatian,

i.e earlier time, from the Don area was found an interesting find of the same type, an anthracite

talisman which had already three signs, and which the

archeologist who found this object called

”scratches” 2. These signs were unusual because the markings were drawn once again, but in a mirror image, which really nears them with the Huns and the widely spread between them euphemisms. The signs look as

follows:

The signs on the coin with later graffiti, described by A.A.Bykov, can be deciphered as Oguzo-Türkic, i.e. the Türkic ”runic” alphabet (because ”runes” have ethnic definition as being Germanic script, Türkic ”runes” is a misnomer, and in this translation the author's ”runic” is given in quotation marks.). The beginning, or the first right sign in the graffiti (lt) in ancient Türkic texts is used in those words where are or are meant sonorous vowels. The graffiti on the coin is read as ltng, in a full ancient Türkic form, i.e. with addition of a vowel, altng, i.e. your al. The idea of the ”live diseased” was connected with a concept of afterlife in the next world. Therefore, in ancient burials, in particular in kurgans, archeologists find a lot of various household, and not only household, objects. The ancient Hunno-Türkic word al means ”any object in front of somebody” 1. In this case it is natural to assume that a word al designates ritual funeral objects - anthracite talisman, golden coin or other objects given as a last tribute to the buried person, and later also in the form of a gravestone monument. For example, on one of the Bulgarian epigraphical monuments is a similar inscription alti or alchi, i.e. his al. As to the mentioned above inscriptions on the gold rings, the German researcher I.Verner, basing on the Byzantian sources, and assuming that the treasury is the inventory of the Bulgar leader Kubrat burial, asked a Byzantist V.Zaijbt to decipher inscriptions on two gold rings. V.Zaijbt deciphered inscriptions as Byzantian monograms (enlacing of initial or individual letters) with a name of Kubrat and title patrician given to him by the Byzantian emperor. Probably, the ”Byzantification” of

the Bulgarian funeral goods was induced by a fact that, in addition to several gold Byzantian objects, in

the treasure were

sixty nine Byzantian gold coins. It is quite a quantity. Though

coins were used as an ornament, but consider that that was a time of the initial stage

of sufficiently intensive

monetary circulation in the Khazar Kaganate, in other words, it

cannot serve as an excuse for under-appreciation of

the Bulgars' culture. Though the apex of monetary

circulation would come later, during that period between

the tribes of the Khazarian Kaganate arose an increased

interest toward the precious metals as the intermediaries not only

in the internal, but also in the external trade. ”Therefore

it is necessary to appreciate a huge role of the Khazarian Kaganate, through which

in the 9th century run the road supplying silver to the

population of the Eastern, and Central, and

Northern Europe”, A.A.Bykov wrote on this occasion. So, judging by the abundance of precious metals, and in particular silver, and to mirror the ”Byzantification” approach, it is possible to ”Türkify” in the same way some customs of the Central and Northern Europe population. By the way, the division of Gothic tribes during the Hunnish period into eastern and western parts could very well arise under an influence of the Huns, because both in the Eastern Europe, and in the north of China this administrative division was typical for the Huns. For example, Kotrags, Kuturgurs, Utragurs or Otragurs etc. are not the names of the Hunnish tribes, as is popularly believed, but the names of administrative regions or military formations connected with their location. For example, köturi (behind) in the Ancient Türkic language means ”to the west”, and utra (front, opposite) means ”the opposite side”, i.e. the east. Another word, otra, which subsequently transformed to urta (horde), means ”middle” 1. The second part of these compound terms is oguz, i.e. a union of tribes, transformed in the western Hunnish dialect to ogor2. If V.Zaibt tried to decipher the monogram of Kubrat's title not as patrician, but as a German könig, i.e. king, that would probably hit the target, because the Hun rulers, judging by numerous pre-Islam Chorasmian coins, had a most ancient title king (with a suffix of belonging), meaning ”belonging to kön”, i.e. to the sun. In relation to Kubrat and Bulgars, Theophanes the Confessor message in his ”Chronography”, dated by 680, is of interest: ”In the days of Constantine of the West, died Kubrat, the ruler of the mentioned Bulgaria and Kotrags”. First, he calls Kubrat a ”ruler”, which is very important, and second, a ruler of not only Bulgars, but also Kotrags. Above, it was noted that Kotragurs are a western administrative division or military formation of the Huns. In the designation ”Kotrag” is dropped ogor, i.e. a union of tribes or an alliance, hence, in this case it is not a military formation But the affix of belonging -g, indicates that the word means ”western” or ”located in the west” (Bulgarian) tribes. From many indicators, for example, the Sassanian or Sassanian type vessels and other objects found in the Middle Itil region and in the east of the Ukraine, seems that Kubrat Bulgars left Itil region, instead of submitting to Khazars, who were partisans of the Türkic Kagan aspiring to create a united state. Also, this is indirectly supported by some written sources. For example, the Arabian historian Tabari in his book ”History of prophets and kings” lists in order the tribes defeated in the 6th century (i.e. ca 552 AD) byTürkic Kagan Sindjibu (Istemi) advancing from the east. After a victory over the Huns-Ephtalites he subdued Bendjer (Bulgars), Belendjers, and Khazars, and after that besieged Derbent. As is known, the early centers of Khazars were in the Northern Caucasus. It is natural to suggest that if the Bulgars lived in the Northern Black Sea area, they would encounter the army of Istemi after Belendjers and Khazars (for outline of events following the death of Kurbat and movement of Bulgarian tribes click here). On the medieval Arabic geographical maps not only location of the seas, lands,

mountains and cities can be traced, but also some historical events and

ethnic composition of the population. For example, on the Idrisi map (12th

century) above the city Bulgar is written: ard Bulgar min at Türok, that is the

Land of

Türkic Bulgars. Recollecting that relatively

recently some researchers translated the traveling notes of the

Arab ambassador to Bulgar ibn Fadlan with designation of the

Bulgar ruler as a king of the Slavs, the awareness of the Arabian geographer

is amazing. More to

the north, it is written: Bakia Bulgar min at

Türok, that is the remaining Türkic Bulgars, still

needs a

historical understanding. The most ancient product in the Kubrat treasure is a silver dish of the Sassanid king Shapur II (?-379), hunting mountain rams. One of the authors of the above-named book writes that the owner of the treasure ”could buy Sassanid silver vessels from visiting traders”. The author probably decided that the owner lived at the Nevsky prospect (central street in St Petersburg)! In another place he writes that the ”eastern traders brought such vessels to the Kama area in exchange for the furs”. In his opinion, it were the Sogdian traders who held in their hands all the trade. But just think for an instant, why a trader would go to the Kama area when from the Central Asia to the northern areas rich with furs is a walking distance, and according to medieval authors, for example Marvazi, only the road from Chorasm to the land of Bulgars took three months. This was also known to ibn Fadlan, who tells that they ”prepared bread, millet, and dried meat for three months” travel. There is also another side of the question. The Sogdian merchants from Samarkand, with all their enthusiasm, could not for centuries venture to the capital of Iran, run a racket, and smuggle from the royal tables of the Sassanian kings innumerable number of artfully made vessels from precious metals to exchange them for furs in the Kama area. Considering that some of the vessels, judging by the motives of the pictures, were connected with Hinduism (for example, an image of four-armed Vishnu on the bottom of a vessel), the Sogdian merchants, before setting off to the Kama area, also had to travel for shopping in India. It is natural to visualize that in the 4th-8th centuries in the Itil and Ural region existed a large cultural center, and that there were luxury goods accessible not to random adventurers or individual Sogdian dealers, but the crowned rulers, and their appearance in the Itil and Ural region is profoundly connected with early history of Bulgars, which in turn is connected with the Central Asia and Ephtalite Huns (known as professing Buddhism), which crushed the Persian army headed by Shahinshah Peroz (ca 468). Peroz had to pay a tremendous tribute to the Huns, and his son Kavad was taken as a hostage and stayed with Huns until the agreed tribute was not paid off1. The traces of Huns in the Itil and Ural region are also traced in the archeological materials. A known archeologist from the Itil region's Germans, V.F.Gening, excavated on the high right bank of Kama more than twenty rich kurgans of alpauts (commanders) with magnificent collection of household objects: two-hand swords with oriental type ornaments on the handle and on the sheaths, an ornamented helmet of a Sassanian type, and other numerous inventory2. The next route of receiving objects from precious metals is connected with dynastic contacts and gifts, and also with numerous own manufacturing, attested by the early Hunno-Kypchak (Chorasmian) inscriptions made during manufacturing of the vessels, and by the written sources. For example, Theophilact Simmocatta (7th century) writes, ”the Türkic government had enriched with Persian gold; all this tribe gave in to great luxury: they forged and minted gilded armchairs, tables, goblets, chairs and stools, made for themselves horse ornaments and full armaments from gold”3 From the Itil and Ural region are known tens of similar vessels with engravings of early Hunno-Kypchak (Chorasmian of Buddhist inclination) pre-”Türkic runic” letters. By now, as seen from the previous discussion, about a hundred words had been read from the inscriptions on the vessels accessible to us. Hence, it is not necessary to presume that the golden rings from the burial treasures are the gifts of the Byzantian emperor, and that their inscriptions are monograms in Greek letters. The outward similarity only indicates that both the Greek, and the Hunno-Kypchak (Chorasmian) alphabet trace their origin to the Aramean alphabet. For comparison and to make facts more convincing, Table 2 assembles the letters from the bowls found in the Itil and Ural region, and published in the Ya.I.Smirnov's book1. Alphabet of inscriptions on bowls from Itil and Ural region (4th-8th centuries) and on rings from Kubrat treasure (7th century)

All letters of the inscription monograms on the rings, adjusted for their placement in a small space, and some other logical and creative design elements, are presented in the Table 2 next to the corresponding letters of the inscriptions on the bowls from Itil and Ural areas, based on the Chorasmian pre-Islamic alphabet. A comparison shows that they belong to the unitary Hunno-Kypchak alphabet. Judging by the inscriptions on all three rings, interesting fact is that not only the name and title of Kubrat are readable, but also are readable one more female and one more male name. As is known, in the Kubrat's burial treasure (25 kg of gold and about 50 kg of silver artifacts) were found two swords (one of them for a lefthander) and other male objects, and also were found female gold bracelets and neck bands, etc. Thus, the so-called Kubrat's burial treasures can turn out to be a funeral inventory of three different persons.

Inscriptions on the rings. Ring of Kubrat Examination of Kubrat's name and title on the ring.

The inscription is read from top down (as on Chorasmian pre-Islamic coins with identical letters) and from right to left. The letters of the inscription are located and transcribed to the Latin as shown. The inscription monogram, according to the rules of early Türkic graphics, when the vowels are not always used, and when necessary to emphasize the absence of the vowel between the consonants, the letters (consonants) are written together (in this case br). The inscription is read Kbrt kingg i.e. Kubrat king (the name of the owner of the ring is shown in bold in the transcription above).

The last letter of the second word, i.e. the ending g, in

ancient Türkic language indicates accusative case of a

noun, i.e. is an affix of belonging, hence, the inscription

means that the ring is ”of king Kubrat”1. Ring of Organa The letters of the following ring are located precisely in the same way as on a ring of king Kubrat:

The letters of the inscription consist of vowels and consonants, and are arranged in the same fashion, from top down and from right to left. In transcribed to the Latin as shown. The inscription is read as Arganda kang, in which the last letter of the second word, like on the Kubrat's ring, is an affix of a belonging. The second word in the Ancient Türkic language means ”father”. For example, in the Kül-Tegin inscription of the beginning of the 8th century, this ancient Türkic word is used in the expression kangym Kagan, i.e my father Kagan. Thus, the inscription is translated as Arganda father, and with an affix of a belonging, the inscription means, that the ring is ”of Arganda the father”. In the first word, the letters rg and nd are engraved attached, emphasizing the absence of vowels between consonants. From the Byzantian sources it is known that Organa (probably, the inscription on the ring from the treasure refers to him) was Kubrat's (maternal) uncle, and was the Bulgarian ruler prior to the beginning of the Kubrat's reign. However, at first sight is absolutely puzzling the absence in the inscription of the Organa title, if this is really his ring.

As seen from the inscriptions in Hunnish alphabet, the Bulgars of the Northern Black Sea were closely connected with the writing culture in the Itil and Ural region area of the 4th-7th centuries, which in turn was connected with the Ephtalites and early forms of Hinduism and Buddhism. The interpretation of the name ”Arganda” adds a special meaning to this connection. ”Arpant” (a Türkic variation is ”argant”) in Sanskrit language means ”saint”, ”one who has reached a last step on the way to nirvana” 2. The absence of the Organa title probably indicates that the gold ring, as well as the mentioned above gold coin from the Khazarian burial, is a last tribute to the deceased royal. This is also indicated by some traits of the engraving, made like the letters of the inscription on the anthracite artifact from the Hunno-Sarmatian burial ”in reverse”. Ring of Queen The inscription on the third ring appears to confirm the hypothesis. The letters of inscription on the third ring, like in the previous inscriptions on the rings, are located in accordance with the rules of the Hunnish graphics. The letters of inscription are transcribed to Latin as shown.

The inscription on the ring is read as Arhndch gkg, i.e Arhandach ögükg. The form of the first word is a feminine gender from Arhant, i.e. ”saint”, ”one who has reached a last step on the way to nirvana”. The root of the second word is ög = mother, and ögük means ”mother (reverent form, akin to ”matron”, ”madre”)” 1. The suffix k, unlike similar to it and located next to it ng, in the inscriptions on two other rings has a characteristic for it enlengthened ”tail” (see Table 2). Last letter g, as in the previous rings, is an affix indicating belonging. Thus, the inscription on the third ring can be translated as ring ”of madre Arhandach”. Form and graphics of inscriptions. Chronologically, by certain features and some roughness of the inscription, the earliest is the ring of Arganda/Organa. In it, in contrast with inscriptions on the other rings, the name is spelled with all vowels not only implied, but also completely spelled out, even though the repeated letters are rendered by variations of the same letter. The first sign in Hunno-Kipchak inscriptions, based on the Chorasmian alphabet, is shown only with the phonetic value of the letter a, irrespective of its location (written more frequently in somewhat more flat lower left side). In the spelling of the second and third signs, in addition to their joined engraving to emphasize an absence of any vowels between them, no deviations (Table 2) are observed. The fourth sign in the inscriptions from the Itil region is found as a or softer æ. The fifth and sixth also, except for conjoint engraving, because there is no vowel inbetween, do not cause any doubts, and at last, the seventh sign (last letter) is found as a, γ or y (y: Russian for u=oo, or ”y” in York?). Comparing with the name ”Organa” given in the Byzantian sources, it can be suggested that the name of the Bulgar ruler, who was ruling before Kubrat, sounded as ”Arganda”. The rendition by different tracing variations of the practically close to each other or identically sounding letters in this case, and certain other special features of the inscriptions, particularly the ”mirror” spelling of some letters, i.e. the euphemism, underline their ritual character and probably testifies about a funeral function of the rings. A similar character of a ”mirror” inscription can be seen on the anthracite object from the so-called ”Sarmatian” burial. Judging by located in the

center part of the ring crossing of the lines, a great

value to which is given by researchers,

it is,

strictly speaking, not a cross of a Byzantian type, but a central part

of the crossing lines of symbol of swastika very important for early

Hinduism and

Buddhism. At the tips of the crossing

all initial or final letters of the words, except for a

letter

designating a capital A in the spelling of a name,

sometimes violating the spelling norms, are engraved on the left,

i.e. they form a swastika symbol. For example, the letter

q in the word qang in the top part

of the crossing is engraved turning to the left, e.i.

mirror-wise (Table 2). The last letter of the same word

indicating an affix of belonging is also ”attached” to

the stem of the crossing

from the left . The last three letters in the name of

Arganda are engraved entirely on the left side of

the horizontal end of the crossing. In the spelling of the

Queen name is observed the same principle. On the Kubrat ring is a left-hand arrangement of

the letters only on the ends of a perpendicular legs of the

crossing. In the ancient Türkic sutra ”Golden shine” about the importance of the meaning of this symbol for believers is stated that suvastik is akat ot teg, i.e. the swastika is equivalent to a sacred fire. Incidentally, in a burial of an Imenkov woman, excavated by E.P.Kazakov, as was already stated, on her breast was found a big talisman in a form of swastika, and in some Imenkov burials archeologists observed traces of ritual fire above the buried. In the Kubrat's burial treasures is an interesting wooden mug covered with gold plates (naturally, the wood had decayed), with a main decorative motive of stylized sacred fire as a burning bush above a special support (funeral urn [?]). By the way, the treasury was found among burned wood and ashes. All three rings have an identical ornamentation of the bottom part of the inscription, which semantically reminds a ”foundation”, the base for a cross on the Byzantian gold coins from the treasury. These terminal bottom parts of the ring inscriptions, consisting of two jointly engraved letters (for the lack of vowels), contain a significant information with the meaning ”belonging”. Reminding a capital letter A, i.e. without two top ”horns” (tribes [?]), with an identical corner down crosspiece, the bottom part of this ”base” is found in a more graceful form as a Bulgarian tamga on the 10th century coins, minted in the Bulgar city, and on other objects from the Middle Itil region (for example, on the bottoms of the ceramic vessels, and by the way, on the bottom of a copper samovar (boiler) from Beljamen, resembling in its appearance an ordinary clay pot with a stovepipe) up to the end of the 14th century. For the sake of fairness it should be mentioned that on the ”Paterna” dish from the Kubrat's burial treasures, not included in the above-mentioned publication, is noticeable an engraved Bulgarian tamga in a form of a capital letter A with a crosspiece corner looking down. On the opposite side of the dish bottom is another tamga. The following, third ring with a name of a Queen has a more graceful inscription, but probably because of a long name and space limitations, it generally has no vowels. However, as is known from archeological studies, women always were custodians not only of the tribal, but also of the religious traditions. In the name of the Queen attention attracts the third sign, written correctly, unlike the name of Arganda, following the Sanskrit, with the right character, a letter h. Probably, existed some monographs or books with religious formulas, frequently mentioned in the inscriptions on the bowls. However because of the shortage of space for the long end of the name to fit in the small surface on the ring, a master-engraver wrote not only without vowels, but also in somewhat original manner. For example, the letter d, like the letter l on the anthracite talisman, was engraved not perpendicularly, but horizontally. And the last letter of the name, i.e. letter ch, is engraved in mirror image, but because of lucidity of the sign shape it does not create any reading problems (Table 2). The third, probably, later

in time ring with the name Kubrat is smaller in size, and

its inscription,

except for the alphabet and crossing, has no

ritual elements or terms of relationship. It tells

that Kubrat wore this ring during his life, and did

not follow the old religious traditions. Inscription

has only a title. The title identical to Kubrat's is usual on

the Chorasmian coins of the pre-Islam period in the 4th - beginnings of the 8th centuries, where in a title

king the first

letter is written with larynx k whereas on the ring the

first letter of the title is engraved with regular k,

like in the spelling of the name of king Zakassak on the

dish 58 from Kama area (see

dish 58), which converge a similar spelling

with the Khazarian (close to the

Mishar dialect of the Tatar language) specifics of the Western Hunnish language. The absence of ancient ritual elements is traced not only in the Kubrat ring, but also in general absence of the inscriptions on bowls from pure gold in his treasures. This fact is intriguing by the event that when the author vas attending hermitage to read an inscription on a gilded bronze vessel from Kama area, the department manager tried to prove that the inscription can only mean a weight of the vessel. However the same scientist, one of the authors of the above-named book devoted to the Kubrat treasures, who was investigating the origin and forms of vessels, does not utter a word that none of them has any inscription indicating their weight, even though these vessels are made not from gilded bronze, as the bowls or dishes with inscriptions, but of pure gold. All this shows that probably Kubrat, as inform the Byzantian authors, since his youthful years was in fact connected with the Byzantine court. After creating for a short time the Great Bulgaria, Kubrat tried to introduce Christianity, but his initiative failed to win his Bulgar subjects and most of the nomadic tribes, and after his death (ca 660 AD) dissatisfied nomadic tribes, as is usually happening in similar cases, switched to the side of Khazars, and the state he created ceased to exist. A part of Bulgars (possibly, a part which accepted Christianity) left to Danube (ca 672 AD), a part returned to the ancestral land, to the Middle Itil region (according to some information, accepting a demand of the Khazarian Kagan (Bardjil, 747 AD) to accept Islam) (after 747 AD?), and those who remained in the Azov lands in the Kara Bulgar (”Black Bulgar”) 1 later were displaced to the Northern Caucasus (Balkars, Karachais). The Karachais (Karachags) may mean not a black people or Black Bulgars, but a Black (Sea) people, i.e. Black Sea Bulgars who relocated closer to the Caucasus Balkars. When this work was practically completed, in my hands accidentally happen to fall a book by Eva Caram with illustrations of several unique finds: rings and pendant earring with inscriptions written in Hunno-Kypchak alphabet2. The uniqueness of these inscriptions is

also emphasized by their repeated use, and notably on different

artifacts. This may indicate that they were a property of

the the same people.

The identity of the inscriptions on the rings with

the names of the owners we already saw

from the inscriptions on the rings from Kurbat burial treasures. However, there are difficulties

in analyzing the signs

on the inscriptions. The ”key” for reading the

letters and

correct reading of inscriptions on the Kurbat burial treasures

were

the already read inscriptions on tens of the vessels from

Itil and Urals area. For the inscriptions on the rings from

the western Bulgaria or Avaria,

where sometimes are different letters, we do not yet have a

”ready” alphabet. Nevertheless, to show the identity of the alphabet of the inscriptions found in Northern Pontic and Hungary, I shall cite as an example a reading on the rings for some easily readable inscriptions. For example, an inscription in the center of exquisite gold earring, like on the rings from Kurbat burial treasures, is read from top down, right to left.

Transcription

The inscription is read aptm (fig. 15) 1 Apyt, or abyt, in Ancient Türkic Language is translated as ”to console” or ”to please”2. However, the word apyt with addition of affix m at the end, i.e. apytym, turns into an abstract noun with a meaning ”consolation” 3. The inscription on the next ring is read from top down, right to left in a circle: Ahsum (fig. 16) 4 Ahsum, or Ahsun, is documented in ancient sources with the meaning ”fierce” as a name of Ephtilite king 5. Thus,

a conclusion can be drawn, that the existence

of such rings, pendant earrings, numerous dishes and other

objects with inscriptions testifies that the Huns, who

lived in the Euroasian open spaces and created original civilization

of the early Middle Ages, had not only proficient skills

in the technical field (pig-iron manufacture, brick making,

casting of their own money, the bronze

ingots, manufacturing of excellent arms like the long two-hand

sword, helmet, chain armour, etc.), but also used their own

writing. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Notes |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

48-1 Simokatta Th. History. - M., 1957. p. 160. 48-2 Khazar rulers were called Kagans, Bulgar rulers were called Iltebers, and after acceptance of Islam, Emirs. And the title of Kubrat is shown on the ring (Author). 49-1 Sadri Maksudi Arsal. Türkic history and Law. - Kazan, 2002. - p. 170 49-2 Bader O.N. and Smirnov A.P. ”Kama Silver” of the first centuries of our era Bartym deposits. - Ì., 1954. - p. 25. 50-1 Bykov A.A. From the history of monetary circulation of Khazaria in 8th-9th centuries // Sources for a history of peoples of Southeast and Central Europe. - Ì., 1974. - Vol. 3. - p. 57. 50-2 Medvedev A.R. Burial of a warrior in Chertov burials // In book: History and culture of Sarmatians. - Saratov, 1983. - p. 126. 51-1 Ancient Türkic Dictionary (ATD) - Ë., 1969. - p. 32, 40, 52-1 ATD.-p. 320,374,618. 52-2 Sadri Maksudi Arsal, Ibid, p. 317. 53-1 Procopius Caesarian. Persian War. Vandal War. Secret History, p. 13,461. 53-2 Gening V.F. Turaev burial of the 5th century AD. Burials of military leaders // From archeology of Volgo-Kama. - Kazan, 1978. 53-3 Simmocatta Th. History. - Ì., 1957. - p. 78. 55-1 Atlas of ancient silver and gold dishes of eastern origin, found in the Russian Empire. - SPb., 1909. 55-2 Ìöhæmmædi Æ. Hunnar hæm Turan yazmalary. - Kazan, 2000. 56-1 Malov SE. Monuments of Ancient Türkic writing. - M. - L., 1951, - p. 44. 56-2 ATD pp. 54, 58. 57-1 ATD. pp. 58, 66. 59-1 Constantine Porphyrogenitus . Rule of empire. - Ì., 1991. - p. 53 59-2 Caram E. Funde byzantinischer Herkunft in der Awarenzeit vom Ende des 6. Bis zum Ende des 7. Jahrhunderts. - Budapest, 2001. 60-1 Ibid, - Table 2,1. 60-2 ATD - p. 247. 60-3 ATD - p. 657. 60-4Caram E. Ibid, - Table 23, 3. 60-5 ATD - p. 71.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 5/31/06 ©TürkicWorld |