Azgar Mukhamadiev

Turanian Writing

Article “Turanian Writing”, in the book “Problems Of Linguoethnohistory Of The

Tatar People” (Kazan, 1995. pp. 36-83)

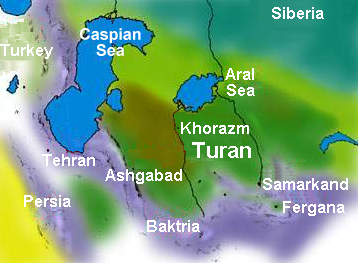

II. Inscriptions on coins of new time

Links

http://kroraina.topcities.com/ca/c_khorezm.html

http://www.grifterrec.com/coins/centralasia/centralasia2.html

Posting Introduction

Turanian Writing

II. Inscriptions on coins of new time

Table 1 Comparative chart of the Turanian and Türkic alphabets

Fig. 5. Coin of Athrikh (305 - ? AD)

Inscription of Bugra (325? - 345? AD)

Fig. 6. A coin of Zakassak (345? - 375? AD)

Inscription of Humkar (505?-535? AD)

Inscription of Buzkhar (535?-565? -575? AD)

Fig. 7. A coin of a Asukdjavar I (ca. 415?-445? AD) or Asukdjavar II (ca. 710-712 AD)

Inscription of Asukdjamuk II (712- ? AD)

The rather large group of the Turanian coins belongs to the minting of the new era . The distinctive feature of the later period coins is the names of rulers minting them. These unique inscriptions, however, were not read satisfactorily in the past.

In his work “Monuments of the past generations” the Turkestan scientist Biruni gives three lists of the kings of Khorezm, ruling, mainly, in the pre-Islamic period [Biruni À., 1957, 48]. Per Biruni, “The Ruler from these kings, when the prophet was sent – peace to him! - was Arsamukh Ibn Buzgar Ibn Khamgari Ibn Shaush Ibn Sakhr Ibn Azkadjavar Ibn Azkadjamuk Ibn Sakhkhasak Ibn Bagra Ibn Afrig “[Biruni À., 1957, 48].

Previously, with rare exceptions, the well informed of the Khoresmian dynasty Biruni name list did not coincide with the names of rulers read by the numismatists on the coins. At the same time, the Turanian alphabet, offered in this work, allows total reading of the names of the rulers, written on the coins, which, basically coincide with the Biruni list. If any name, given by Biruni, is absent on the coins, it means, that there were no coins issued with the name of a given ruler, or that the coins with the name of a given ruler were not found until present. Let’s acquaint in more detail with the inscriptions of the Turanian coins of the new era:

1. Obverse. In a circular ornamental frame is an image of a beardless ruler to the right in a crown with “ears”.There are no inscriptions [Vainberg B.I., 1977, Table XIX, G I].

Reverse. On the left side on a monetary field is the tamga of Turan, and in the center is a rider with the royal attributes, with a fluttering ribbon on the neck and with a scepter in the left hand.

Fig. 5. A coin of Athrikh

From top down and right to the left is the inscription consisting of three words (Fig.5):

![]()

kηütrgi äthrkh

The inscription is translated as 'King of state Athrikh'. The coin is not dated. Probably, from the time of the minting of the antique Turanian coins passed a lot of time. It is observed not only the distinctive shape of some letters, but the title of the ruler has changed and the place of minting is stated in a different way.

The first word, as was noted above, is found in the monument in honor of Kül Tegin almost in the same form of shape [ Mukhamadiev A.G., 1990, 46]. Like S.E.Malov, I also have read this word, which consist of three consonant letters, as kengu, i.e. with the letter å in the middle. The similar reading connects a title kengu ('born by the sun') with a relatively late inscription of the Türkic word Kön - 'sun'. However, the presence of this title at the Western Huns, for example, judging by the inscription on the cup of the son of Attila Diggizikh, and preserved at Germanic peoples in the form of the king - 'king' allows to assume that the pronunciation of this word in the Hunnish time was nevertheless king, with the letter i in the middle, and with a soft back consonant in the beginning (i.e., khing). Judging by some data, and taking into account that in the Türkic language the roots and the derivatives of the roots of words barely change, the word in this form comes from the depth of the millenniums. For example, in the language of Maya, in which the dictionary lexicon, as is known, is replete with many pra-pra-Türkic words, yash k’ing means 'young sun' [ Knorozov Yu.V., 1975, 242] (See A.Karimullin "Proto-Türks and American Indians").

The second word trgi - 'state' - with the suffix of belonging i at the end, in the Türkic monuments of the beginning of the 8-th c. is in the form turug, i.e. with two consonants in the middle [ Malov S.E., 1951, 22, 16th line]. Considering that the letter r in the word trgi on the coins in the later centuries is emphatically connected with the consequent letter g, between them are no vowels. Therefore, the word should be read as turgui, and it is possible to assume, that it designates not simply a 'state', but a term already becoming the name Turgu (Turgan).

S.P.Tolstov read this word on the coins as mlk, i.e. 'king' [Tolstov S.P., 1938, 133]. Taking into account the distinctive outline of the letter r, it is really a rather tempting reading. However, the various and distinctive outlines of the letters of the coin inscriptions are expressed sufficiently precisely, and there is no place for doubts [ Mukhamadiev A.G., 1990, 40]. Moreover, as we will see later from the inscriptions on the vases, in front of the names of the kings, like on the coins, is a title king, and adding a second title melek would be meaningless.

The third word on the coin is the sufficiently clear written name of the ruler of the Turan Athrikh. The time of the Athrikh rule is not established exactly (in fact, it is, 305-? AD - Translator's Note), and the beginning of the minting of the second period of the Turanian coins is therefore debatable. In the mentioned Biruni list, Athrikh is in the first place. Once again he is mentioned in the connection with the construction of a palace in the 616 of the Iskander era (Alexander the Great). Therefore, the years of rule of Athrikh belongs to that time (i.e. ca. 303 AD - Translator's Note). But, with what year begins calendar of “Iskander era”,is not established [ Mukhamadiev A.G., 1990, 43]. In her monograph, B.I.Vainberg gives a more fruitful hypothesis that in the source, which used Biruni, was, it seems, the date in the Khoresmian, i.e. in the Turanian era [ Vainberg B.I., 1977, 80]. In this connection it should be recognized, that Biruni's “Iskander era” is not without a sense. Biruni, doubtlessly, knew about the special, friendly relations of the Turan with the Baktria, evidenced by the portraits of Eucratid on the antique Turanian coins.

Thus,if the Biruni's calendar of “Iskander era” begins with appearance of the imitation coins of Eucratid in the 2-nd c. BC, then Athrikh ruled in 40-eth of 5-th c. AD, which coincides with the other indirect data.

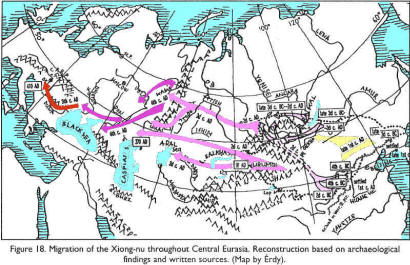

Athrikh revived Turan after the Kushan dominance and, it seems, he is a contemporary of Attila. Makhmud Kashgari gives his, widespread in the Türkic epos of 11-th c., title Alp Er Tonga, i.e. 'Giant Leopard', which also inherited his offsprings. Athrikh, as a legendary person of the Iranian epos, is frequently met under a name Afrosiab – the leader of the Turanians hostile to Iran.

|

Posting Note In the late Avesta hymns, Turya (Tur in Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh) is an umbrella term for various enemies of Zoroastrism, and Shahnameh's Afrasiab is called Fran(g)rasyan, an elder son of king Fereydun. In Shahnameh, Fereydun is a son of Abtin, Avestan Athbiya with a transparent Türkic etymology of As Biy = Biy of Ases and a killer of dragon Aji Dahaka, and a descendant of Jamshid. Fereydun, together with Kaveh, a head of Parthian clan from Hyrcania (Gorgan, from Yirk = Tr. “nomad”), revolted against tyrannical (Babilonian) king “Zahhak” (Pers. Aji Dahaka), replaced him as a king and ruled the country for about 500 years (Parthian, or Arsacid era, 247 BC – 224 AD). Jamshid, in Tr. Jamshad = Prince Jam, aka = Prince Yam, is a Türkic mythological personality recorded in the Indian Rigveda as divine Yama with his twin sister and beloved spouse Yami, and a figure of 7th c. AD Yimek/Kimek genealogical myth also carrying a title “shad”. The fact that for Persian Avesta the twins Yama and Yami are unknown, and Yama already appears with the title “shad” indicates a Türkic source for the mythology, which ultimately may be either Türkic or Indian. Yimeks/Kimeks also derived their origin from Jamshid/Yama Shad. Genetically, the current 7% of Indian genes in the modern Central Asian population, coupled with an absence of typologically Persian genes, points to a much more significant proportion of the Indian blood among the ancient nomadic population (say, 20%), and explains the presence of parallel mythologies in the Türkic and Indian etiologies, but the Eurasian spread of the water twins mythology from Tiber to Amur points, first, to its primordial timing, and secondly to the mounted nomads that could spread far and wide, as only the Kurgan Culture of milk-eaters could have spread. Among the receptor mythologies are Roman (Romul and Rem), Greek (Dioskur twins), Mediterranian (Minos and Radamantis), Persian (Jam and Jima), Ossetic Nart epos (Uryzmag and Hamyts, without attribution of the source to Türkic Digors or Hurro-Urartian Nakhs), Zoroastrian (Mashya and Mashyana), Indian (Yama and Yima), Altai (Nama and Yime), and Far Eastern Ulches on the Lower Amur (Ulchi twins). In Türkic mythology, most well-described are Kimek and Balkar Nart legends, and modern form Cem (pronounced Jem). All above twin plots are united by a presence of mother water goddess, a water dragon being a most popular figure, Roman (wife of a river deity), Greek (daughter of sea god Glavk), Mediterranian ( Europe, daughter of Ocean), Ossetic Nart epos (daughter of a sea king), and Ulches (Water Tiger Temu duse), among others. The dragon Aji Dahaka in the Athrikh/Afrasiab/Alp Er Tonga/Franrasyan

genealogy is also loaded. Its form is Ashtak, and Ashide 阿史德 in Chinese rendering, and they

happened to be respectively the maternal dynastic clan of the Ashina, also known as Goktürks, who

gave the name to what today we call Türks and Oguzes. The Ashtak tamga is

|

By the contents of the Türkic eulogy on the death of Alp Er Tonga he was probably killed:

Fate waited for a chance,

Setting a hidden trap.

Men incited men,

Escape - how be rescued?

[Stebleva

I.V., 1976, 210].

In the spelling of the name Athrikh on the coins, the second letter is rather distinctive. It is met in the beginning of the name of the son of Attila, Diggizikh, in the inscription on a golden plated cup, which will be discussed later. However, this letter is not phonetically either f, nor ð as in the Diggizikh name, but is a letter for the specific Hunnish phoneme, resembling c and ð simultaneously. Afterwards in the Türkic language, it seems, it was transformed to t or ð. The ancient Türkic name Atruk, the root morphology of which resembles the above name, ascends, it seems, to the ancient Türkic word atrak - 'yellow', 'gray'. Considering the euphemisms of the Huns, probably, the name of Athrikh in itself included the concept of a leopard or a lion. In any case, the “Arslan Khan”,and the name of the following after Athrikh ruler “Bugra Khan”,were Karakhanid titles.

Quite interesting are the types of the Bugra coins, the ruler following Athrikh. The Turanian coins from this period become more refined and diverse. For the first time on the face of the coins appear inscriptions carrying additional details.

2. Obverse. In a circular ornamental frame is an image of a ruler in a crown with “curls” on the top. There are no inscriptions. [ Vainberg B.I., Table XIX, G III].

Reverse side. At the left on a monetary field is the tamga of Turan. In center is the rider with the usual royal attributes. Top to down and right to left is a precise inscription:

kηü trgi bugra

The inscription is translated as 'King of state (Turan) Bugra'. Bugra in Biruni list is listed next after Athrikh.

On the following type of the coins for the first time in the history of the minting of the Turanian coins on the obverse appears a small inscription in front of the face of the ruler (GIII-4):

xutü (khutü)

i.e. 'Lord'. On some types of the coins the first sign of an inscription represents the letter h, i.e. the word is written as Íètü [Vainberg B.I., 1977, Table III].

On the back, like on the previous type of the coins, is the inscription: “King of state (Turan) Bugra”.

The following type of the Bugra coins sharply differs from the other types in decoration (GIII-5).

Obverse. In a dotted border is a portrait of a ruler in a crown with an image of a camel on the top. In front of the face of the ruler for the first time appear name and title. Top to down is a continuation of the inscription:

kηü trgi bugra

i.e. 'King of state (Turan) Bugra'.

Reverse side. On a left-hand side is a Turanian tamga, and in the center part is a rider with the royal attributes. On the right top to down is a two-word inscription, first of which is difficult to read:

sdq ürknsηk

The inscription is read as 'Shad of Urgench'.

It seems, the Bugra’s crown with an image of a camel on top is not accidental. In the ancient Türkic language bugra means a ‘two humped camel’.

In the inscription “Shad of Urgench” on the reverse side of the coin, the first character of the first word and the fifth character of the second word represent hard s of the Turanian alphabet.

The similar lettering of the word “Shad” is noted also in the Türkic monuments [Malov S.E., 1951, 70]. The word “Urgench” is written in the form Urkencheneg, i.e. by all rules of the ancient Türkic language, with the characteristical ending of the noun in accusative inflection case.

Judging by the coins, rather interesting appear not only the change in the form of the Bugra’s crown, but also the contents of the inscription. For the first time is mentioned on the coins the city Urgench, and not Khorezm. If on the previous coin Bugra was xutü (khutü),i.e. 'Lord', on the inscription of the last coin, he has become “Shad of Urgench”,i.e. actually a dependent ruler, though the title king on obverse is retained. Similar metamorphoses, it seems, are explained by the events that in the east is rising a powerful young state of the Kök Türks - “Blue Türks”,the Shad of whose Khagan, it seems, became the ruler of Turan.

The following coins belong to the minting of Zakassak (on Biruni’s list - Sakhkhasak), with decoration of several somewhat different types.

Fig. 6. A coin of Zakassak.

3. Obverse. An image of a ruler in a crown with “curls” above. Like on early Bugra’s coins, there are no inscriptions [Vainberg B.I., 1977, Table XIX, GII].

Reverse. On the left side is the Turanian tamga, and in the center is a rider with the royal attributes. Right to left runs an inscription consisting of three words (Fig.6):

kηü trgi zkssk

The inscription is translated as 'King of state (Turan) Zakassak'.

On the obverse of the following types of the Zakassak coins (GII-1), in front of the face of a ruler, is an inscription, and behind the portrait is a continuation of the inscription - top to down “King of the state (Turan) Zakassak”.

On the reverse of such coins, similar to the Bugra’s coins, is an inscription of several words, but for a reliable reading a visual familiarization with the coins is necessary.

The following group of coins somewhat deviates by their decoration from the traditions established during the rule of Bugra.

5. Obverse. A head of a ruler to the right with a crown in a form of a camel in a large dotted circular frame. There are no inscriptions.

Reverse. In the center is a large image of tamga as a trident candelabra. Right to left in a circle is an inscription (Vainberg B.I., 1977, XIX, G12]:

kηü trgi humkr

i.e. ‘King of state (Turan) Humkar'.

According to the Biruni’s list, Khamgari ruled before Buzkhar, but his coins by decoration and distinctive tamga would fall out of the series of the Turanian coins. The Khamgari coins in Khorezm are found infrequently. But they are a mass material at the excavations of the monuments of the ancient Kerder (area 300 km north-west of Khorezm - Translator's Note) [Vainberg B.I. 1977, 63].

4. Obverse. An image of a ruler in a crown in a dotted frame [Vainberg B.I., 1977, Table XIX, GIV-6 (7)]. In front of the face of the ruler, top to down is an inscription, and behind it is a continuation of the inscription:

kηü trgi bsxr

i.e. ‘King of state (Turan) Buzkhar'.

Reverse side. On a left-hand side the usual Turanian tamga, and in the center part is a rider with the royal attributes.

On the right top to down is a fairly clear inscription of two words:

sdq ürknsηk

i.e. 'Shad of Urgench'.

On some types of the coins on the back there is the following inscription:

sdq pqrq

i.e. 'Shad of Bukhara'.

Buzkhar in the Biruni list (Buzgar) is listed after Humkar. However, judging by the decoration of the inscriptions, the Buzkhar coins are closer to the circle of the Bugra-Zakassak coins. Per Biruni, Buzkhar was the predecessor of that Arsamukh, who ruled at the time, “... when the prophet was sent”.Accepting this time for the year of the Muhammed birth, i.e. 570 AD, it comes out that Buzkhar ruled sometime in the middle of the 6-th c.

The coins of Arsamukh and the coins of the following rulers of Turan, Sakhr and Sabri from the Biruni’s list, are not known yet.

The following group of the coins also differs by the distinction in the minting, but of another character, namely strengthening of the signs of the external influence.

Fig. 7. A coin of a Asukdjavar

6. Obverse. A portrait of a ruler looking to the right in a crown with “curls” above. On the neck is a necklace of two strings of beads. In front of the face of the king is an inscription with Sogdian italics, which was read by V.A.Livshits as sivrshpn and is perceived by the researchers as a name of a ruler minting the coin [Vainberg B.I., 1977, Table VI, G V].

Reverse side. On the left is a tamga of Turan, and in the center is an image of a rider with the royal attributes. In a circle around the rider is the inscription (Fig.7):

kηü trgi äsükžugr

The inscription reads ‘King of state (Turan) Asukdjavar’.

The name of Asukdjavar is fairly clearly engraved in the form Asukjugr, i.e. Asukdjaugar. The name is easily separated into two independent parts: Asuk and djaugar- 'warrior'. The first part of the name, it seems, is a name of the legendary Ashok tree (in Türkic ajuk), under which Budda’s mother bore her son.

The second part of the name in the form yauari - ' trooper' - is found in the Bulgar religious epigraphical monuments of 14-th c. [Khakimzyanov F.S., 1978, 80].

It is thought that the inscription on the obverse in the Sogdian italic type, is connected to the endoethnonym of the Türkic Sir people, the organizers of the campaign in the Turkestan in the beginning of the 8-th c. [ Mukhamadiev A.G., 1990, 53]. According to the texts of the Türkic monuments in honor of Kül Tegin and Tonyukuk, when the Khagan of Sirs, after fording the Irtysh river, went on a campaign in the Turkestan, at first he was confronted by the Turgs (Turgishes), i.e. by the inhabitants of Turan. But when in the monument the story touches on the particular peoples, it mentions on ok and ikh taty, i.e. 'Huns and their Iranian speaking subjects'. For example, Kapagan Khagan, talking of the irrational policy of the Turgs Kagan, which lead to his death, says that in the result of his policy “...the people on ok has suffered subjugation” [Mukhamadiev A.G., 1990, 57].

In the war against the Türks-Sirs the ruler of the Turgs allied with the Chinese and Kirghiz. But in the battle at Bolchu at the end of the 711 AD he was defeated and captured, and the Yabgu and Shad were executed. However the Turgs Khagan managed to escape, even though the Hun army remained on the side of the Türks-Sirs. Afterwards, after running into the Arabs and appraising the situation, he moved to the side of the Türks-Sirs. “Then came all Sogdian people led by Asuq... “[Malov S.E., 1951, 69] was said in the monument. The name of the Turgs Kagan Asuq is quite similar to the name on the coin, and, it seems, the talk is of the same person - Asukdjavar.

Asukdjavar, (Asukdjavar II, ca. 710-712 AD, in this episode. The period of Asukdjavar I, whose coin maybe shown in the Fig.7, lived ca. 415?-445? - Translator's Note), who ruled in the Khorezm in the 712 AD, until the first campaign of Kuteiba, was killed by the rebels. Per Biruni, “when Kuteiba Ibn Muslim conquered Khorezm for the second time, after “falling off” (from the Islam) of its inhabitants, he made Asukdjamuk Ibn Asukdjavar a king” [Biruni, 1957, 48].

Thus, though the ‘Khagan of Sirs’ is mentioned on the coins, Asukdjamuk was set on the throne by Kuteiba. He was the first of the rulers of the Turan who accepted Islam, to which on the coin testifies the engraved Moslem part of his name - Djamuk.

7. Obverse. In a circular doted frame is a portrait of a beardless ruler facing to the right. There are no inscriptions [Vainberg B.I., 1977, Table V, XX, G 13].

Reverse side. To the left is a Turanian tamga with slightly changed shape. From its top in a circle is an inscription:

kηü trgi žömuq

i.e. 'King of state (Turan) Djomug'.

On some types of coins there is a distinctive inscription, indicative, like on the Asukdjavar coins, that in this period the state of Turan gradually loses its independence. There are no customary titles, but words are clearly read [Vainberg B.I., 1977, Table V, 1371]:

kη sri

i.e. 'King of Sirs...'.

The name of the ruler is illegible, but most likely it is Djomug, who on similar coins is described as a representative of Sirs. The dynastic relationships of the Türks-Sirs and Türks-Unuk (Huns) are barely known. Kapagan Khagan wrote about the ruler of Turgeshes (Asuq), “Turgesh Khagan was ours Türk, [from] our people. As he did not understand [his benefit] and was guilty before us, [himself] Khagan has died, his orderlies and rulers were also killed, the people Unuk (On-Ok - Translator's Note) has suffered subjugation “[ Malov S.E., 1951, 38 (19)].

The last from the series of the new time mints and before the appearance of the Arabian imitations are the Abdullakh coins, carrying the reflection of the peculiarities of the political situation in the Turan in the first half of the 8-th c.

8. Obverse. A portrait of a beardless ruler in a crown facing to the right. Continues Asukdjavar type issues. In front of the face of the ruler, like on his coins, is the inscription in Sogdian italics which was read by V.A.Livshits as “k’nsvr” – as a name of a ruler (Vainberg B.I., 1977, 62, G VI].

It seems that it is the same inscription as on Djomug coins with description Kan or King of Sirs. Moreover, on the back of these coins is a well read name of a ruler written in the Turanian letters:

kηü trgi rbdulloγ

The inscription reads 'King of state (Turan) Sir Abdullah''.

On some types of the coins of Abdullah in addition to the Turanian and Sogdian

inscriptions is also an Arabian inscription. On one of such coins found in Tatarstan, on

the reverse above the body of horse is said “Muhammed”,and the

Sogdian inscription on obverse of the coins is replaced by an Arabian one,

which the various researchers read differently (

Vainberg B.I., 1977, 62].

50

The clearly emphasized “dj” in the spelling of the word “warrior” - djaugar indicates the “djocking” dialect of the Khoresmians of the 6-th c. AD. The Bulgarian equivalent “trooper” - yauari with the initial “y” indicates the “chocking” dialect of the Bulgarians of the 14-th c.

”k’nsvr” = “King of Sirs” , i.e. the same text as the Türkic legend.

For the Kök Türks, the name of Asukdjavar was Asuq, and “djavar” = “warrior” was a title-type adjective, so the names are not only similar, it is the same name.

West Side