XIONGNU (Hsiung-nu), the great nomadic empire to the north of China in

the 2nd and 1st centuries BCE, which extended to Iranian-speaking Central Asia and

perhaps gave rise to the Huns of the Central Asian Iranian sources.

Origins.

The Xiongnu are known mainly from archaeological data and from chapter 110 of the

Shiji (Historical Records) of Sima Qian, written around 100 BCE, which is

devoted to them. Comparison of the textual and archaeological data makes it possible to

show that the Xiongnu were part of a wider phenomenon—the appearance in the 4th century

BCE of elite mounted soldiers, the Hu (Di Cosmo, 2002), on the frontiers of the Chinese

states which were expanding to the north. The first mention of the Xiongnu in Chinese

sources dates to 318 BCE. Archaeologically, these Hu cavalrymen seem to be the heirs of a

long development (the Early Nomadic period, from the end of the 7th to the middle of the

4th century BCE), during which the passage from an agro-pastoral economy to one dominated

at times exclusively by equestrian pastoralism had taken place. (Author

refers to a fact that all archaeological explorations were conducted in the settlements,

thus missing the sparse nomadic component, the presence of which is archeologically

detected in cultural influence and kurgan burials. The agro-pastoral economy belongs to

the indigenous farming population) Among these peoples, in

the 4th and 3rd centuries BCE the Xiongnu occupied the steppe region of the northern

Ordos as well as the regions to the northwest of the great bend of the Yellow River.

Numerous archaeological finds in Inner Mongolia and in Ningxia demonstrate the existence

of a nomadic culture that was socially differentiated and very rich, in which both iron

and gold were in common use and which was in constant contact, militarily as well as

diplomatically and commercially, with the Chinese states (in particular Zhao to the

southeast). This culture seems to have directly inherited those which had preceded it in

the region, but on a wider scale (the Xiongnu pottery of Xigoupan or Aluchaideng is a

developed form of the Early Nomadic pottery of Taohongbala; development continued on the

site of Maoqinggou from the Early Nomadic period to the Xiongnu period, with a transition

to nomadism sometime around the sixth century BCE; for a different view see Minaev, 1996,

p. 11, who, on the basis of funerary materials, places the origins of the Xiongnu further

to the east, south of Manchuria (Upper Xiajiadan culture), and the response of Di Cosmo,

1999, pp. 931-34). We do not know what influence the Saka cultures to the west may have

had in this development. (Under Saka culture is meant the Scythian

culture in the east, from Caspian to Ordos and beyond. Under transition apparently is meant the

transition of local Mongolian and Tungus farmers to agro-pastoral economy induced and in

symbiosis with the large-nosed and hairy Hu Huns)

The name of the Xiongnu (χiwong nuo according to

Karlgren) has also been related to other tribal names of Antiquity which have a rather

similar pronunciation, following the vague identifications of the Shiji

(Pritsak, 1959, strongly criticized by Maenchen-Helfen, 1961). Furthermore, the language

of the Xiongnu has been the subject of the most varied hypotheses based on the few words,

mainly titles or names of persons, which have been preserved in the Chinese sources:

Altaic, Iranian (Bailey, 1985, which has not been followed) and Proto-Siberian (Ket). At

present, the hypothesis of Pulleyblank (1962) in favor of Ket seems to be the most

well-founded (Vovin, 2000), although it is by no means certain that all of the tribal

groups of the confederation belonged to the same linguistic group nor that the late

Xiongnu distich was representative of the language (Di Cosmo, 2002, pp. 163-65).

On the name of the Huns we have four fundamental postulates:

1. Alphabetical form of Chinese coding 匈奴 Xiongnu, Hsiung-nu, etc is Hun (W.B. Henning

The Date of the Sogdian Ancient Letters (BSOAS,. 1948, pp. 601-615 [315])

2. Numerous previous Chinese renditions of the name Hun are traceable from the first

arrival of literacy in China, in the forms Chunwei 淳維, Hunyu 葷粥,

Xunyu 獯粥, Shanrong 山戎, Xianyun 獫狁, Xiongnu 匈奴.

The form Xiongnu was codified in the first united Qin empire, which in 3rd c. BC disposed

of all insular variations in favor of 匈奴 with literal meaning “ferocious

slave” (Wei Zhao et al., Book of Wu, p. 2849; Lin Gan 林幹, Xiongnu shiliao

huibian 匈奴史料彙編, Vol. 1, p. 1, Beijing, Zhonghua Shuju, 1988; Sima Qian et al., “Records of the Grand Historian”, Ch. 110; Ying Shao, The Meaning of Popular Customs, Fengsutung,

http://kongming.net/encyclopedia/Ying-Shao )

3. Post-Former Han form 恭奴, introduced by Wang Mang in

10 CE, that retained the old phonetics of 匈奴 but

changed the meaning from “ferocious slave” to “good slave” (Taskin V.S. 1984. “Materials

on history of Dunhu group nomadic tribes”, p.15, Moscow, Science).

4. Nearly all Türkic tribes had their name terminated with “hun”, displaying a notable

phonetic consistency independent of the Chinese rendering. The same applies to composite

tribes, like Tuiuhun (Zuev Yu.A.

Ethnic History Of Usuns, Works of Kazakh SSR Academy of Sciences, History,

Archeology And Ethnography Institute, Alma-Ata, Vol. VIII, 1960, p. 12: “all or nearly

all ancient Turkish tribes (Turks, Kirkuns, Agach-eri, On-ok, Tabgach, Comans, Yomuts,

Tuhses, Kuyan, Sybuk, Lan, Kut, Goklan, Orpan, Ushin and others) carried the name “Huns””.)With all the

various renditions, it is apparent that they all refer to the same underlying endonym,

Hun. B.Karlgren's typologycal reconstruction may or may not have produced accurate alphabetical phonetization for an isolated case in the Archaic period, but with the actual phonetization at hand, the academic phonetical

exercises can only demonstrate the degree of applicability and reliability of the various

linguistic theories and practices on phonetical reconstructions.

On the Jie identification with the Huns we have a positive Chinese testimony that Jie is a toponymic name of a branch of the Huns. Jie were a splinter from the parental tribe Qianqui, a community

mentioned in the Jin-shu among the 19 Huns' pastoral rout communities. Chinese

annals use Jie, Huns, and Hu interchangeably, with a preferential use of more generic

form Huns for Jie, and Hu for Huns and Jie once the subject is defined upfront (Taskin

V.S. Materials on the history of nomadic peoples in China. 3rd - 5th cc. AD. Issue 2.

Jie, p. 6, Moscow, Oriental Literature, 1990, ISBN 5-02-016543-3)

On the Jie Huns' distich we have an unmistakably straightforward Turkic

reading. Theoretically, or speculatively, the generic Chinese phonetics of the 4th c. is

different from the modern phonetics. At the same time, the tumultuous 4th c. during the

16 States period brought into Chinese governance Huns and other Northern people, changing

Chinese language in the direction of its modern form. In practice, at least in respect to

the Jie Huns' distich, for the three words spelled out in Chinese, the modern Chinese

phonetization perfectly transmits a modern Turkic phrase, allowing philologists to hone

their conversion theories:

| Chinese |

秀支 |

替戾剛 , |

僕谷劬 |

禿當 |

| Romanized Mandarin |

Xiù zhī |

Tì lì gāng |

Púgǔ qú |

Tū dāng |

|

English

Phonetization

|

Sü chi |

Ti li gang |

Pugu chu

|

Tu

dang |

| Chinese to English |

Army |

go out |

Pugu |

capture |

| Türkic |

Süči (Süchi) |

tiligan |

Pugu'yu |

tutar |

| Türkic to English |

Army-man |

would go |

Pugu (he) would |

capture |

| Comment |

-či (= chi/ji) - std. occupational affix |

-gan - past participle, 3ps, perfect tense verbal affix |

-'yu - future conditional verbal transitive affix |

capture in 3rd person future tense ablative ending |

On the last word, tudan/tutar = capture, G. Doerfer made an observation: “It is

interesting to note that the Uzbek (i.e. Karluk, i.e. Uigur)

loanwords in Dari, or Afghan Persian, often show different forms from those in Tajiki and

more often coincide with the standard Persian forms (cf. Kiseleva and Mikolaichik). Thus

to Tajiki qapidan “to catch” corresponds Dari and literary Persian qapidan.

The Uzbek loanwords in literary Persian, literary Tajiki, and literary Dari still need to

be investigated; however, it appears that Dari contains fewer Turkish loanwords than

Tajiki.” (Encyclopaedia Iranica, 1995, Volume 5, Sect.14, p. 231) Parsing 劬禿當 as

“chu-tu-dan” would bring us to the Persian/Dari/Tajiki qapidan “to catch”,

and this Uigur loanword may excite somebody to claim an Iranian attribution of the Hunnic

language. The ultimately Uigur loanword was borrowed in its entirety, with the Türkic

ablative ending. On Enisean theory click here. With the direct statements supplied by the Chinese annals, it takes a special, largely

futile, effort to obscure the issue |

The Xiongnu Empire. The Xiongnu confederation was destabilized in 215 BCE by

the offensive campaign of a China recently unified by the Qin, who sent the general Meng

Tian to occupy and fortify the pastoral areas of the Ordos and to drive the Xiongnu and

their shanyu Touman to the north. The Xiongnu tribes reunified under the

charismatic figure of Touman’s son Maodun in 209, crushed the Emperor Gaozu, forced him

to sign a humiliating treaty in 198, and reoccupied the Ordos. The status quo then

prevailed until 134 BCE, a period during which the Xiongnu secured their pre-eminence

over the steppe societies of East Asia. This period was brought to an end by the

initiative of the Chinese, who expelled the Xiongnu to the north of the Gobi in 121 and

119 BCE.

In the domain of archaeology, the military domination of the Xiongnu gave rise to the

following phenomena: First, the development of a proto-urbanization within the Xiongnu

sphere as, for example, fortresses in the excavation of Ivolga on the Selenga by A.

Davydova (1995); villages, whether fortified or not, as in Dureny (Davydova and Minyaev,

2002), where handicraft and agriculture were practiced in addition to animal husbandry,

which has led to a rereading of the Shiji and Han shu in which it is

actually specified that the shanyu must have had towns built in order to

preserve the grain they received as tribute, and that they constructed a capital (Minaev,

1996); secondly, the enrichment and very clear sinicization of the contents of the tombs

of the Xiongnu aristocracy, such as the tombs of Noin-Ula, a royal cemetery, investigated

in 1924 by Kozlov (Rudenko, 1962), in which were found numerous deluxe objects imported

as much from China as from the Iranian-speaking West, or the tombs excavated recently at

Egiin Gol (Giscard, 2002) (The accompanying goods found in the kurgan graves could as well come from the Turkic-speaking West, where the steppes around oases were populated by Turkic-speaking horse pastoralists, where Huns were in control of the Tarim basin, and had close relationship with Usuns and Kangars, whose control, in turn, extended to the Caspian Sea and included “Sute” Sogd, of which Weishu tells under entry for 457 AD: “The country of Sute is situated west of Pamirs. It is what was Yancai

in ancient times. It is also called Wennasha. It lies on an extensive swamp and to the northwest of Kangju. It is 16,000 li distant from Dai. Formerly, Huns killed the king and took the country. King Huni was the third ruler of the line.” Huns controlled the Silk Road and had access to all goods

traversing the continent. Older

kurgan graves from Minusinsk depression, Issyk, Pazyryk and others also had grave goods

from China and West, they had villages and forts).

The Xiongnu military domination also gave them control of Central Asia and put them in

direct contact with the Iranian-speaking populations: In 176 BCE Maodun crushed the

Yuezhi of Gansu, then subdued the Wusun, Loulan, the Hu Jie and “twenty-six peoples” of

the region. In 162 the shanyu Laoshang again crushed the Yuezhi refugees in the

valley of the Ili and forced them to migrate to the southwest into sedentary

Iranian-speaking Central Asia (Sogdiana, Bactriana). At that time all of Central Asia

recognized, at least formally, the suzerainty of the Xiongnu: “whenever a Xiongnu envoy

appeared in the region [i.e., western Central Asia] carrying credentials from the Shanyu,

he was escorted from state to state and provided with food, and no one dared to detain

him or cause him any difficulty” (Shiji, tr. Watson, p. 244).

| Yuezhi are Tokhars ruled by royal Ases; first they were defeated by the Huns

in ca 206 BC, but in 162 they were crushed by Usuns, not the Huns. Chinese records

identify Yuezhi with Ephtalite Türks, also named Abdaly and branded White Huns Wusun are Usuns,

modern Uisyns of the Kazakhstan Senior Juz (Senior Confederation), kicked out from

Jeti-su “valley of Ili” by Tokhars and sheltered by the Huns, of which Chinese preserved a romantic story.

Usuns stayed with the Huns for 15-20 years, and then returned to Jeti-su and kicked out

Tokhars. Usuns were a separate branch of the Huns. Jeti-su has a rich trove of kurgan burials

Loulan was a small oasis principality south of Lop Nor Lake in Tarim basin,

with 14,000 population during the Former Han dynasty, but apparently a jewel from the

taxing viewpoint

Hu Jie are Kians, aka Qiang 羌族, aka Huyan, aka Jiang 姜/羌, an old maternal

dynastic tribe of the Huns, by the Han time replaced by Sui/Hui/Yui Uigurs. From exogamy

laws, it can be inferred that Qiangs were sufficiently removed from the Luanti Huns to

allow marital partnership. Under the name Qiang, at about 1,000 BC, they were a maternal

dynastic tribe of the Zhou. Their Hu descent must have been marked by deep-set eyes,

prominent nose, and hairy facial appearance. Kians must have been a mighty tribe.

Laoshang

(174-161 BC) is a Chinese calque of the Türkic traditional title Aga = senior,

elder, a title of respect; in the name Laoshan-Giyui-Shanyu 老上單于 the “Laoshang“

means in Chinese “old and elevated”, Giyui = “[A]Giyui“ = “Aga-Yui” = “Reverend-Yui”,

with Yui = Uigur; the initial vowel does not register in Chinese; Aga is still

an active title of respect in Türkic and neighboring cultures |

Nevertheless, their control was primarily exercised in the northeast of the Tarim Basin and Turfan,

with the Lob Nor as a western frontier: The Office of the Commander in Charge of

Slaves, responsible for raising taxes and corvées, was established near Karashahr

(Qarašahr). Control of the West seems to have been limited to the collection of tribute

from the Wusun (Dzungaria) and Kangju (middle Syr Darya and Sogdiana), while further to

the south the Yuezhi (Bactriana) were hostile to them (Even

centuries later, up untill 9th c. AD, the household tax collected first by the Huns, then

by Bulgars, then by Avars, then by Khazars, then by Ruses was one pelt from a household

per year, a practically invisible amount).

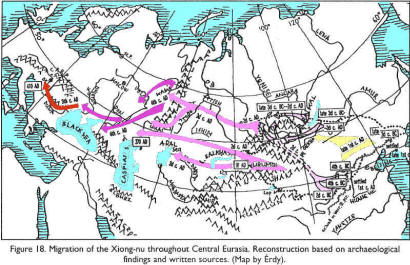

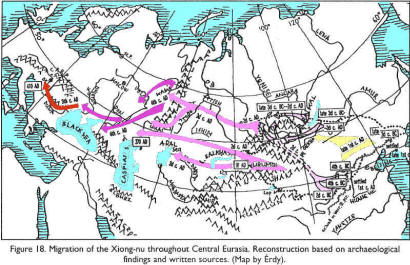

Having been pushed back to the north by the Chinese, the Xiongnu entered into a period

of internal divisions, during which the shanyu rapidly succeeded each other and

the local Xiongnu kings fought over the central government. To the west, between the

years 115 and 60 BCE, the weakening of the Xiongnu confederation gave rise to a struggle

between the Chinese and the Xiongnu for control of the western regions. The principal

events of this struggle included the missions of Zhang Qian in search of alliances in 137

and 115 BCE, the raid on Fergana (Ferghana) by a Chinese army in 101 BCE, and the battles for control of the region of

Turfan (Jushi) between 67 and 60 BCE. The Office of the Commander in Charge of Slaves

lasted until 60 BCE, at which time it was replaced by its Chinese equivalent, the

Protectorate General of the Western Regions (see Yü Ying-Shih, p. 133).

In 57 BCE the disintegration of the confederation led to its division between five and

then two shanyu, one in the South (Huhanye) who submitted to China in 53 BCE,

the other (Zhizhi) controlling the North and West. The latter, finally taking refuge in

Kangju, carved out a kingdom in the valley of the Talas and was defeated there by the

Chinese general in 36 BCE, an episode that marks the farthest advance of the

Xiongnu and Chinese armies into the Iranian-speaking West (Daffinà, 1969).

|

The idea that Kangar somehow was Iranian-speaking is based on the foundation glued

together from enthisiasm and ambitions. Not that we are in a complete darkness, a

heavyweight Constantine Porphyrogenetus identified Kangars as rulers of Bajanaks, they

are heavily documented as speaking Türkic. Kangar ruled Sogd, which spoke an areal

language closest to modern Pashto, and an underemined number of farming oases, which

might be suspected of speaking Horesmian/Sogdian-related language, but to turn Zhizhi

seeking shelter with his Kangar vassals and in-laws into some kind of intrusion into some

kind of “Iranian-speaking West” is a figment of egocentric imagination, the horse

husbandry nomads lived around and within the oases long before and long after Zhizhi

epizode. It was the very same Zhizhi people that provided technology, transportation, and

manpower for caravan trade extending to Rome and Byzantine before the Silk Road blossomed

and became a reknown Silk Road. It is a shame that the Kangar history has not been

written yet, Kangar was a major powerhouse in the Central Asia during an exceedingly long

period of time, it was a powerful kingdom that controlled N.Pontic for 150 years, but so

far its history was only exploited for advancement of primitive self-aggrandizement and

overt falsification. Even the traces of the Kangar language in the Balkans, among the

Slavicized Croatians and Bosnians, are attributed to the Ottoman Turkic time, and are

beneath the attention of the same very philologists who advance fictitious concepts

against all odds. Ditto the traces of the Kangar language among many Kangar splinters in

Central Asia and Mongolia. |

The ensuing peaceful period ended when the Xiongnu took advantage of troubles in China

(reign of Wang Mang, 9-23 CE) and widely recaptured control of the West before once again

splitting into two groups, the Southern Xiongnu and the Northern Xiongnu, in 48 CE. The

first group took refuge in the north of China in 50 CE, giving rise to areas of Xiongnu

population within the frontiers between Taiyuan and the Yellow River that would endure

for several centuries. Their last shanyu disappeared at the beginning of the 3rd

century, but the Xiongnu, though highly sinicized, preserved their identity and played a

major role in the disturbances and plundering that put an end to the Jin dynasty in North

China at the beginning of the 4th century (Honey, 1990).

While the Northern Xiongnu for a time succeeded in playing a role in the West (their

armies intervened at Khotan and Yarkand after 61 CE), China regained control of the

region of Turfan in 74 CE and chased them from Mongolia: the shanyu took refuge

in the Ili valley in 91 CE, while many Northern Xiongnu tribes surrendered to China and

were settled within the frontiers. The Northern Xiongnu, with several thousand men,

continued to intervene at Hami and in the region of Turfan throughout the first half of

the 2nd century. We know nothing of their fate: in the Wei Lue, written in the

middle of the 3rd century, the Xiongnu are completely absent from the piedmont north of

the Tianshan (Chavannes, 1905).

Xiongnu and the Huns. Could these Xiongnu have given rise to the Huns who

appeared on the Volga from the year 370 CE before they invaded Europe? The question is

highly controversial and has been the subject of numerous works since de Guignes first

proposed the identity of the two groups in 1758. The reference in one of the very early

Sogdian documents conventionally called the Ancient Letters of 313 to

the Xwn pillagers of Luoyang, where the Chinese sources speak of the Xiongnu, seemed to be decisive evidence in favor of this identification (Henning, 1948) before O.

Maenchen-Helfen attempted to prove on several occasions that the two were unrelated,

mainly using archaeological data, but also via critical examination of the texts. While

we are indebted to the latter for having demonstrated the complexity of the Hun question

(Maenchen-Helfen, 1973), and while his prudence has in the main prevailed (see for

example Sinor, 1989, Daffinà, 1994, and also a recent synthetic view in Golden, 1992, pp.

57-67 and 77-83), an attempt will be made here to show that Maenchen-Helfen’s reasoning,

quite valid from an ethnic point of view (the Huns were basically composed of a

conglomerate of peoples), cannot be accepted in terms of political identity (la Vaissière, 2005b).

First, it seems possible to prove that the names are indeed identical. In 313 it was a

Sogdian merchant writing in the Gansu corridor who, in a letter to a correspondent at

Samarqand, described with precision the plundering of the Southern Xiongnu in China and

called them Xwn, a name which must be connected to that of the Huns (Henning,

1948, a point conceded by Maenchen-Helfen, 1955, p. 101). Should it be connected to that

of the Xiongnu (χiwong nuo)? This connection poses no

problems to specialists in Chinese phonology (Pulleyblank, 1962, p. 139), and above all

it is difficult to see what other origin one could give to this name which is always

given as an equivalent to that of the Xiongnu in all of its first Central Asian

occurrences: aside from the Sogdian Ancient Letter, one must also cite the Buddhist

translations of Zhu Fahu (Dharmarakşa), a Yuezhi of Dunhuang, who in 280 CE translated

the Tathāgataguhya-sūtra from Sanskrit to Chinese, and rendered Hūņa by

Xiongnu (Lévy, 1905, pp. 289-90, the Sanskrit version is no longer extant, but

there exists a Tibetan version which gives Hu-na), and then did the same in 308

in his translation of the Lalitavistara (of which a Sanskrit version is extant)

(Daffinà, 1994, p. 10).

The Sogdians had been acquainted with the Xiongnu since the extension of their empire

to western Central Asia in the 2nd century BCE, and one can no longer doubt the quality

of the evidence (contra Sinor, p. 179, who presupposes that the name of the Huns

is generic without asking why, and above all Maenchen-Helfen, 1955, who unconvincingly

attempts to disparage this eyewitness testimony by comparing it to purely theoretical

examples); solid reasons are required if we are to consider that the Sogdian merchant and

the Yuezhi monk of Dunhuang did not give them their real name, for reasons which remain

unknown (despite Parlato, 1996).

|

Since it is known that re-population of Central Asia after a millennium of

dessication started around 10th c. BC from three directions, one from the south by

agricultural people, and two by related Timber Grave Kurgan horse husbandry nomads from

two directions, the first from the N.Pontic steppes, and the second from the east, with

the second displaying higher degree of Mongoloidness, who settled in symbiotic

co-existence for the next 2 millennia, generally occupying different neighboring climatic

zones, there is as much of a reason to suggest that the Huns reached China from the

Central Asia as there is a reason to suggest that they reached China from the South

Siberia; moreover, no boundary exist between the Central Asia and South Siberia, and the

difference may be only in today's terminology. The idea of autochtonous origin of the

Huns in the China Zhou territories is ruled out archeologically, and the first Huns to

come to China as Zhou people are identified by the Western scholars with the Türkic

(or Pra-Türkic) people with their distinct archeological signature. |

But these texts do not imply that the Huns of Europe or Central Asia after 350

were themselves descendants of the Xiongnu: one can imagine that the name Xwn

or Huna — an accurate word for describing the Southern Xiongnu who

plundered North China in the 4th century as well as the ancient Xiongnu, known as far as

India — may then have been used again for very different nomadic peoples. Further still,

we have proof of such usage: in Sogdiana in the 8th century, the Turks are sometimes

named Xwn (Grenet, 1989), and certain Huns of some Khotanese texts could not be Xiongnu

(an example in Bailey, 1949, p. 48). But this generic name did not develop from nothing,

and only the Xiongnu hypothesis can account for it.

Moreover, the Wei shu, taking up information precisely dated to 457, states:

“Formerly, the Xiongnu killed the king (of Sogdiana) and took the country. King Huni is

the third ruler of the line” (trans. Enoki, 1955, p. 44). This leads us to place the

“Xiongnu” invasion of Sogdiana in the first half of the 5th century. Here, too, there is

hardly any reason to doubt this direct testimony stemming from the report of an official

Sogdian envoy in China (see Enoki, 1955, pp. 54-57). Also, the personal names found in

the Sogdian caravaneer graffiti of the Upper Indus (3rd to 5th century CE, see

Sims-Williams, 1989 and 1992) frequently include the first or last name Xwn, whereas it

no longer exists in the later corpus of texts (the Chinese documents of Turfan), which

reflects the presence of Hun invaders in Sogdiana and the fusion of the populations (la

Vaissière, 2004, pp. 77-78; 2005, pp. 81-82) during a precise period of time.

| This is a case of immaculate conversion: the cavalry captured Sogdiana, dismounted,

grabbed hoes, and started happily rule the land, live in constrained quarters, and sweat cultivating terrain, all in

order to fuse according to prescription. In all other cases nomads keep tending to their

horses in the pastures outside cities, trade with the cities, and gently rule the cities,

fusing a little, but generally keeping their own horses, lifestyle, traditions, laws, and

language that outlasted any invasion |

Nevertheless, this still does not imply that the invaders were Huns/Xiongnu, but at

least that they claimed to be. In order to proceed further, it is first necessary to

stress the extent to which the testimony of the Wei shu concerning the Xiongnu in the West is isolated. Beginning with the hypothesis of de Guignes, scholars have

sought on several occasions to identify a westward migratory movement of the Xiongnu. For

a long time, the episode cited above (the establishment of the shanyu Zhizhi in

the valley of the Talas) was used for that purpose: the Xiongnu who accompanied Zhizhi to

the West were considered to be the ancestors of the Huns of Europe. This is impossible,

since the Chinese sources emphasize the small number of these Xiongnu (Daffinà, 1969, pp.

229-230). Even if one takes into account the latest reports of the Northern Xiongnu north

of the Tian Shan (153 CE), two centuries still separate them from the invasion of

Sogdiana, while we have no reason to suppose the existence of a westward movement of the

Southern Xiongnu. But other passages in the Wei shu speak of “remnants of the

descendants of the Xiongnu” as western neighbors of a branch of the Rouran (Juanjuan), to

the northwest of the Gobi around 400 CE (Wei shu, 103.2290). This information is

not without interest, for it implies the survival of a Xiongnu identity far to the north,

well beyond the field of vision of the Chinese sources, in the very place one would

expect to find Huns/Xiongnu shortly after some of the main body of their troops had

passed the Volga and others the Syr Darya, leaving these small groups behind them.

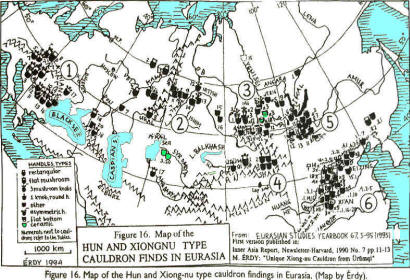

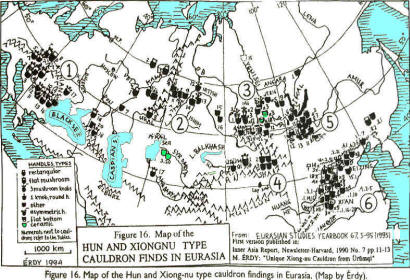

From an archaeological point of view, there are now few doubts that the Hunnic

cauldrons from Hungary are indeed derived from the Xiongnu ones. Moreover, they were used

and buried on the same places, the banks of rivers, a fact which proves the existence of

a cultural continuity between the Xiongnu and the Huns (Erdy, 1994; de la Vaissière,

2005b).

The Huns of Central Asia thus consciously succeeded the Xiongnu and established

themselves as their heirs, and an authentic Xiongnu element probably existed within them,

although it was probably very much in the minority within a conglomerate of various

peoples. This is the only hypothesis that accounts for all of the known facts given the

current state of our information.

The Chinese annals are quite specific about 19 Hunnic pastoral routs, each one

supposedly owned by a tribe or a splinter of a tribe, ruled by a hereditary chieftain

that generally did not belong to the ruling tribe, but was a member of the confederation

parlament that represented his tribe, voted on state affairs, and elected shanyu;

these 19 subdivisions may be considered Huns proper; every one of the 19 subdivisions had

a marital partner, which could also be another of the 19 tribes, or be an outside

traditional marital partner, like a member of Tele confederation, Mongol tribes, Tungus

tribes, Tibet tribes, Tokhar tribes, Usun tribe, and tribes that escaped Chinese

attention of the time. The position of the foreign tribes would be subordinate to the

Türkic tribes, at least initially, but with the build-up of the kinship, the border

between Türkic confederations and foreign tribes and confederations would become fuzzy.

The three-tier state system was so ingrained that it was a state structural scheme for

every consequent state. The state was also divided into three wings: Left or Eastern Wing,

Right or Western Wing, and a Center Wing, eash with assigned Hun tribes, Türkic at large

tribes, and vassal tribes. The control of the wings belonged to the members of the

dynastic coalition. It is quite probable that the 19 Hun proper tribes initially

consisted of the same complement of the dynastic coalition, upper allied Türkic kin

tribes, and lower foreign vassal and marital partner tribes, but by the time the Chinese

annals first recorded them, they already fused into a homogenous Hunnic-proper

confederation.

The examples of fused tribes are Tuiuhuns (Kian Huns + Tibetans ),

Syanbi (Huns + Mongols), Tabgach/Toba (Huns + Mongols), Western Mongols (Huns + Mongols),

White Tatars (Uigur Huns + Mongols), modern Qiangs (Kian Huns + Tibetans). Some Türkic

tribes were a fusion of Ogur and Oguz tribes, i.e. of Central Asian and South Siberian

tribes: Tele, for example, had the Ogur Uigurs and Karluks, while the majority were Oguz

tribes. |

The Xiongnu/Huns in Central Asia in the 4th century. We shall not deal here

with the Huns who appeared around 370 CE on the Volga prior to their invasion of Europe

(see Maenchen-Helfen, 1973), nor with the Central Asian dynasties of the 5th century that

are sometimes called Hunnic in the sources (on the Kidarites, who appeared only from the

year 420, see Grenet, 2002; see KIDARITES). In Central Asia, the first references that must be taken into account

date from 350 CE. Ammianus Marcellinus then mentions for the first time in his narrative the eastern enemies of

the Persians, the Chionites (XVI, 9, 3-4). In 356, Šāhpur II fought against the

Chionites in the East, then

concluded an alliance: the king of the Chionites, Grumbates, participated in the siege of

Amida (Diyarbakir) in 359 (XIX, 1, 7). This name is now attested around the year 430 in

the Bactrian documents for a prince of the kingdom of Rōb (north of the Hindu Kush) in

the form Gurambad (Sims-Williams, 1997, 13 doc. 4). The influence of Avestan

Hyaona might suffice to explain the form Chion, which is divergent in

comparison with Xwn, Huna, and Hūņa. These Chionites could

have reached the Sassanid frontiers in 350 CE. Boris Marshak, for other reasons (1971, p.

65) considers the Chionites to have been not Huns but mountain-dwellers of the Hindu

Kush, an hypothesis supported by the fact that Ammianus Marcellinus, who knew of both the

European Huns and the Chionites, never makes the connection between them (Sinor, p. 179),

and possibly by the name of Gurambad. It would then be necessary to situate the invasion

of the Xiongnu/Huns one or two generations later: at that time the Armenian sources show

that the Sassanids, between 368 and the death of Šāpur II (379), were defeated by a “king

of the Kushans” reigning at Balê- (Faustus of Byzantium, V, vii and V, xxxvii, tr.

Garsoian, 1989, pp. 187-98 and 217-18), and the Kushano-Sassanid kingdom collapsed at

that time. Moreover, it was at the end of the 4th century that the alchonno of

Kapisa and Gandhara began to strike their own coins re-using those of Šāpur II, which

would be perfectly consistent chronologically (on these coins see Alram, 1996, who

associates them with the Kidarites, and more generally Göbl). But this reading is

contested as some coins can be read alchanno, a name which should be linked with

the indian legend rājālakhāna.

This invasion and those that followed it shattered the sedentary economy of

Iranian-speaking Central Asia: Bactriana, ravaged for more than a century (until the

expansion of the Hephtalites in the middle of the 5th century), declined as the principal

center of population and wealth, due as much to the nomadic offensives as to the vigorous

Sassanid resistance, while Sogdiana, which had been rapidly conquered, recovered. In

Bactriana, all of the available data agree in giving the idea of a sharp decline of the

region in the course of the period from the second half of the 4th century to the 6th

century: neglected irrigation networks (valley of the Wakhsh), multiple layers of burning

(Chaqalaqtepe), abandonment of sites (Dil’beržin Tepe, Emshi Tepe), barren layers in the

stratigraphy of sites (Tepe Zargarān at Balê-), necropolises over ancient urban areas

(Termed, Dal’verzintepe), sacking (Karatepe). In contrast, to the north the populations

of the region of the Syr Darya, whether of the delta (Džetyasar culture) or of the middle

course (Kaunči culture), seem to have taken refuge in Sogdiana under Hun pressure and

rapidly returned the abandoned lands to cultivation. Conversely, the sites of the

Džetyasar culture were widely abandoned, and at the middle course of the Syr Darya the

city of Kanka diminished to a third of its initial surface area (Grenet, 1996, de la

Vaissière, 2002, pp. 105-16). It may also be noted that the sites of Džetyasar are close

to the areas in which the Western sources place the European Huns prior to their crossing

of the Volga. These peoples who arrived from the north added to the local Sogdian

populations, which did not disappear. Sogdiana rapidly rebuilt itself in the 5th century

under a stable Xiongnu dynasty, and then under the Kidarites.

Bibliography:

M. Alram, “Alchon und Nēzak. Zur Geschichte der iranischen Hunnen in Mittelasien,” in

La Persia e l’Asia Centrale da Alessandro Magno al X secolo, Atti dei Conveigni

Lincei, 127, Rome, 1996, pp. 519-54.

H. W. Bailey, “A Khotanese Text concerning the Turks in Kantsou,” Asia Major, NS 1, 1949, pp. 28-52.

Idem, “Iranian in Hsiung-nu,” in Monumentum Georg Morgenstierne, I, Leiden, 1981, pp. 22-6.

Idem, Indo-Scythian Studies: being Khotanese Texts, VII, Cambridge, 1985, pp. 25-41.

T. J. Barfield, “The Hsiung-nu Imperial Confederacy: Organization and Foreign Policy,” Journal of Asian Studies 41/1, 1981, pp. 45-61.

É. Chavannes, “Les Pays d’Occident d’après le Wei Lio,” T’oung Pao, series II, vol. VI, 1905, pp. 519-71.

P. Daffinà, “Chih-chih Shan-Yü,” Rivista degli Studi Orientali, 1969, 44/3, pp. 199-232.

Idem, “Stato presente e prospettive della questione unnica,” in S. Blason Scarel, ed., Attila. Flagellum dei?, Rome, 1994, pp. 5-17.

A. Davydova, Ivolga archaeological complex. Part 1. Ivolga fortress (Archaeological Sites of the Hsiungnu, 1), Saint Petersburg, 1995.

A. Davydova, S. Minyaev, Complex of Archaeological Sites near Dureny (Archaeological Sites of the Hsiungnu, 5), Saint Petersburg, 2002.

N. Di Cosmo, “The Northern Frontier in Pre-Imperial China,” in M. Loewe and E. L. Shaughnessy, eds., The Cambridge History of Ancient China, chap. 13, Cambridge, 1999, pp. 885-966.

Idem, Ancient China and its Enemies. The Rise of Nomadic Power in East Asian History, Cambridge, 2002.

K. Enoki, “Sogdiana and the Hsiung-nu,” Central Asiatic Journal 1, 1955, pp. 43-62.

M. Erdy, “An Overview of the Xiongnu Type Cauldron Finds of Eurasia in Three Media, with Historical Observations,” inB Genito, ed., Archaeology of the Steppes, Naples, 1994, pp. 379-438.

N. Garsoian, tr., The Epic Histories Attributed to P’awstos Buzand (Buzandaran Patmut’iwnk), Cambridge, Mass., 1989.

P.-H. Giscard, “Le premier empire des steppes,” in J.-P. Desroches, ed., L’Asie des Steppes d’Alexandre à Gengis-Khan, Paris, 2002, pp. 135-41.

R. Göbl, Dokumente zur Geschichte der iranischen Hunnen in Baktrien und Indien, 4 vols., Wiesbaden, 1967.

P. Golden, An Introduction to the History of the Turkic Peoples,Turcologica 9, Wiesbaden, 1992.

F. Grenet, “Les ‘Huns’ dans les documents sogdiens du mont Mugh (avec un appendice par

N. Sims-Williams),” Études Irano-aryennes offertes à Gilbert Lazard, Cahier de

Studia Iranica, 7, 1989, pp. 165-84.

Idem, “Crise et sortie de crise en Bactriane-Sogdiane aux IVe-Ve s. de n.è.: de

l’héritage antique à l’adoption de modèles sassanides,” in La Persia e l’Asia

Centrale da Alessandro Magno al X secolo,Atti dei Convegni Lincei, 127, Rome, 1996, pp. 367-90.

Idem, “Regional Interaction in Central Asia and North-West India in the Kidarite and

Hephtalite Period,” in N. Sims-Williams, ed., Indo-Iranian Languages and Peoples,Proceedings

of the British Academy 116, London, 2002, pp. 203-24.

W.B Henning, “The Date of the Sogdian Ancient Letters,” BSOAS, 12/3-4, 1948, pp. 601-15.

D.B Honey, The Rise of Medieval Hsiung-Nu: The Biography of Liu-Yüan,Papers on Inner Asia, 15, Bloomington, 1990.

É. de la Vaissière, Histoire des marchands sogdiens,Mémoires de l’IHEC, 32, Paris, 2004.

Idem, Sogdian traders. A History, Leiden and Boston, 2005

Idem, “Huns et Xiongnu,” Central Asiatic Journal, 49, 2005b, pp. 3-26.

S. Lévy, “Notes chinoises sur l’Inde V. Quelques documents sur le bouddhisme indien

dans l’Asie centrale,” Bulletin de l’École Française d’Extrême-Orient 5, 1905,

pp. 253-305.

O. Maenchen-Helfen, “Pseudo-Huns,” Central Asiatic Journal l, 1955, pp. 101-16.

Idem, “Archaistic Names of the Hiung-nu,” Central Asiatic Journal 6, 1961, pp. 249-61.

Idem, The World of the Huns. Studies in Their History and Culture, Berkeley, 1973.

B. I. Marshak, “K voprosu o vostochnykh protivnikakh Irana v V v.” [On the problem of the Oriental enemies of Iran in the fifth century], Strany i narody Vostoka, 10, 1971, pp. 58-66.

S. Minaev, “Archéologie des Xiongnu en Russie. Nouvelles découvertes et quelques problèmes”

Arts Asiatiques 51, 1996, pp. 5-12.

S. Minyaev, Derestuj Cemetery (Archaeological Sites of the Hsiungnu, 3), Saint-Petersburg, 1998.

S. Parlato, “Successo euroasiatico dell’ etnico žUnni’,” in La Persia e l’Asia Centrale da Alessandro Magno al X secolo (Atti dei Convegni Lincei, 127), Rome, 1996, pp. 555-66.

O. Pritsak, “Xun, der Volksname der Hsiung-nu,” Central Asiatic Journal 5, 1959-60, pp. 27-34.

S. I. Rudenko, Kul’tura Khunnov i Noinulinskie kurgany [The Culture of the Huns and the Kurgans of Noin-Ula], Moscow, 1962.

N. Sims-Williams, Sogdian and other Iranian Inscriptions of the Upper Indus, I-II, Corpus Inscriptionum Iranicarum, II/III, London, 1989-1992.

Idem, New Light on Ancient Afghanistan. The Decipherment of Bactrian, London, 1997.

D. Sinor, “The Hun Period,” in D. Sinor ed., The Cambridge History of Early Inner Asia, Cambridge, 1990, pp. 177-205.

A. Vovin, “Did the Xiong-nu Speak an Yeniseian Language?” Central Asiatic Journal 44-1, 2000, pp. 87-104.

B. Watson, tr., Sima Qian, Records of the Grand Historian: Han Dynasty II, New York, 1993.

Ying-Shih Yü, “The Hsiung-nu,” in D. Sinor, ed., The Cambridge History of Early Inner Asia, Cambridge, 1990, pp. 118-49.

November 15, 2006

(Étienne de la Vaissière)

Originally Published: November 15, 2006

Last Updated: November 15, 2006 |