L.T. Yablonsky

Cranial vault modification as a cultural artifact:

a comparison of the Eurasian steppes and the Andes

Human Biology 56 (2005), 1-16, doi:10.1016/j.jchb.2004.09.001, © 2004 Elsevier GmbH. All rights reserved

Links

Foreword

L.T. Yablonsky

Cranial vault modification as a cultural artifact:

a comparison of the Eurasian steppes and the Andes

The practice of intentional cranial vault modification in the Eurasian steppes is addressed focusing on how the practice was used to respond to changes in society. In the steppes appeared vault modification, the forms are seen in the cemeteries of the Syr Darya and Amu Darya River deltas. Dramatic homogenization of the custom resulted from the conquests of the Huns, traceable in the pattern of modification and temporal changes. The alterations of the practice resulting from foreign contact are considered in light of vault modification's role as a malleable cultural artifact..

Cranial vault modification is a deliberate and permanent altering of head shape during infancy. It is unique, however, among body modifications in that it is an irreversible act performed by adults on children. There is no chance to alter head shape in adulthood since adult cranial bones have fused together and are no longer malleable. The practice therefore reflects an investment of time and effort by parents and is a sign of an ascribed identity. Vault modification has a long and varied history. Our perspective on vault modification (is that it is) as a feature that conveys cultural information.

(The area) include small-scale cultures as well as large states and empires. They have endured periods of contact and conquest and have survived these periods with numerous alterations to the social fabric of the group that may manifest in head shape. This analysis focuses on changes in cranial modification resulting from the conquests of the Huns in Central Asia.

Social role of head shaping (Excerpts)

It is critical to examine anthropological explorations of ethnicity given the preponderance of evidence suggesting that cranial vault modification served to denote group identity (Latcham 1937-38; Soto-Heim 1987; Gerszten 1993; Hoshower et al 1995; Lozada Cerna 1998; Blom 1999; Torres-Rouff 2002). Ethnicity, as defined by Barth (1998, p.11), ‘‘has a membership which defines itself, and is identified by others, as constituting a category distinguishable from other categories of the same order’’. This implies that ethnicity is a cultural construction in constant interaction with that of other groups (Jones 1996, p. 67). Ethnic groups must self identify and furthermore, cultural differences are strengthened when ethnicities interact (Jones 1996, p. 71; Barth 1998, p. 16). Consequently, the recognition of ethnic groups by outsiders is pivotal to their functioning (Kelly & Kelly 1980). These ethnic differences can become visible in material culture and, particularly, in cultural practices. Like mortuary behavior, cranial vault modification is such a practice. Ethnicity is often a social construct used to amplify cultural distinctions that are overlain on biologically similar populations. Although the relationship between cultural traits, biological traits and ethnicity is not straightforward, particularly given the dynamic nature of ethnicity, it does provide an interesting viewpoint from which to perceive distinctions between groups (Jones 1996, p. 67).

When the populations are under stress they sought ‘‘their time-honored reassurance of ethnicity’’ (1996, p. 71) through similar symbols on nearly all of their material culture. This falls into line with Jones' (1996, p. 71) assertion that ‘‘ethnicity involves the objectification of cultural difference vis a vis others in the context of social interaction’’. In the case of the data examined for this project, it is not possible to reflect a fluid relationship through the permanent act of cranial modification. While not arguing for an interpretation of an essential identity portrayed through head shape, it is more likely to be a reflection of a tradition within the group, and one whose display is of great importance. As Blom (1999, p. 10) has noted, ‘‘groups with similar affiliations are expected to share cranial modification styles. On the other hand, unrelated groups or those trying to emphasize their differences could display their distinctiveness with differing head forms’’. Head shape is a strong statement about group membership. Finally, artificial cranial vault modification, as a permanent symbol on the body, can also be viewed more generally as a vehicle through which individual social identity is constructed. Wobst (1977) has stated that style is integral to the process of information exchange. He argued that style is intended to convey information to a socially distant group. Most studies of style in archaeology are confined to material objects such as beadwork or clothing, however, cranial modification, like other forms of body art, can be understood to convey information and function in a similar role (Smith 1997; Blom 1999).

In addition to stylistic interpretations of the body, several writers have perceived the body as malleable and constructed by the society in which it participates. In this literature, the human body is not seen as a purely biological phenomenon. Synnott has argued that ‘‘the body social is many things: the prime symbol of the self, but also of the society... The body is both an individual creation, physically and phenomenologically and a cultural product; it is personal and also state property’’ (Synnott 1993, p. 4). Others posit that the body is both controlled by and is a component of the actions of society (Shilling 1993, p. 70). It is of particular interest in the analysis of cranial vault modification that the body can be constructed as a symbol of the society; as a marker of group identity. The body can be made into a symbol of an ethnic group or a social community, with members of the group sharing a common identity. This is eloquently put by Polhemus (1978, p. 151) in his discussion of scarification practices among the Nuer: Although they are placed on individual bodies, they are (in a sense) not personal or idiosyncratic but serve instead to symbolize the fact that an individual has become a member of the social group, the cultural collective, the 'social body.' These scars are, for the Nuer, symbols of the socialization process and of the collectivity of their existence. Many body modifications are used to project group membership. These can take the form of temporary changes such as dress, paint and headgear, or be more permanent alterations to the body. These varied changes often reflect the different relationships that are being conveyed. Achieved positions are often represented through temporary means, such as the costumes of leadership in a particular society. In contrast, cranial vault modification, besides being permanent, is a mark placed on the body of an infant. In this sense it is particularly representative of social values. Meskell (1998, p. 158) expounds on this notion of the social or cultural body by noting that ‘‘the body represents the particular site of interface between several different irreducible domains: the biological and the social, the collective and the individual, structure and agent, cause and meaning, constraint and free will’’. The use of the human body to create differences and similarities in a society where they do not necessarily exist biologically is a crucial conception for understanding the use of intentional head shaping in prehistory. The very mark of the altered head is a signifier of great value. Moreover, it is one that would have been highly visible and sparked recognition or some form of understanding among the members of the group, and even individuals outside it.

Cranial vault modification in the Eurasian steppes (Excerpts)

Zhirov (1940) was the first scholar to write a synthesis of cranial modification in ancient Russia. He developed a classificatory system for the various forms of deformation by associating each type with the features of a modifying apparatus. Using material accessible to him at the time he described four main varieties of cranial vault modification in eastern Eurasia: occipital, coronal-occipital, occipital-parietal, and circular (Zhirov 1940). Artificial cranial modification has ancient roots in Eurasia. The earliest cases in the archaeological literature date from the Bronze Age (ca. 2000—1000 BC; Firshtein 1974), among peoples of the "Catacomb" culture as well as those from southern Turkmenistan. Over time, however, the practice was abandoned in both of these regions. Cranial vault modification became common again among the nomads and shepherds of the Eurasian steppes during the early Iron Age (ca. 700-500 BC; Yablonsky 1999). Between these periods, intentionally modified skulls do not appear in Eurasian archaeological samples.

As a result, there appears to be no continuity in the development of this practice in the region. On the contrary, it appears that the custom of head shaping arose independently in these different times. The first instances of cranial modification during the subsequent period are from the early Iron Age and date from 700 to 600 BC. These are found in the Southern Tagisken cemetery, located at the delta of the Syr Darya River east of the Aral Sea area (Fig. 1; Itina & Yablonsky 1997, pp. 73-74). This is within the territory of the earliest state in the Eurasian steppes, Chorasmia. Of the 26 excavated individuals from the Southern Tagisken cemetery, nine display some form of cranial alteration (34.6%; Table 1).

|

|

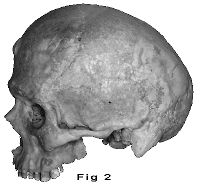

The majority of these skulls had unintentional modification of the occipital bone (n = 7), an artificial flattening of the occipital and the posterior (back) portion of the parietal (side) bones. This style of modification is well known in Central Asia. According to ethnographic data from contemporary populations of (Türkic ) pastoralists, the flatness of these bones results from the custom of rigidly affixing the child into a cradle and is a byproduct of this particular cradling technique (Gershenovitch 1929; Vifleemskaya 1930; Richkov 1969). One skull from the Southern Tagisken cemetery had deliberate flattening of both the occipital and frontal bones (coronal-occipital deformation), resulting from opposing pressure on the frontal and occipital simultaneously. This form was rare in the early Iron Age, although it eventually became widespread in Central Asia between 200 and 1 BC (Ginzburg & Trofimova, 1972). Finally, one skull from the Southern Tagisken cemetery displayed occipital-parietal modification, a form in which the main pressure on the skull affects both the posterior and superior portions of the parietals and the occipital bone (Fig. 2). The burials found in the Southern Tagisken cemetery are the oldest evidence that adults in this area intentionally modified the head shape of infants. The appearance of deliberate head shaping in this cemetery serves as a forceful sign of incipient social differentiation among these populations. Over time, the practice would be commonplace, seen at the Sakar-Chaga cemeteries of northern Turkmenistan (ca. 600 - 400 BC) and eventually throughout the area occupied by the Chorasmian state. The predominance of both coronal-occipital and occipital-parietal deformation in the Chorasmian territory speaks to the first attempts to shape the head in order to create a specific external appearance; an appearance that physically distinguishes individuals and groups of individuals from each other. This idea is strengthened by the fact that after 500 BC occipital-parietal deformation became one of the clearest signs of Chorasmian identity among pastoralists (Yablonsky 1999) (This observation is valuable because it coincides with the appearance of the historical records that allow identification of the nomadic husbadry tribes in the Middle Asia).

| Fig. 2. Occipital-parietal cranial modification (Sakar-Chaga 1, Kurgan 18, adult male) |

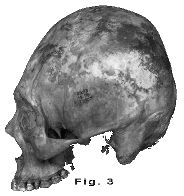

Fig. 3. Tabular cranial modification (Solcor 3, Tomb 107, adult male) |

Fig. 4. Circular cranial modification (Titicaca, Catalog No. B/2237, adult male) |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Cranial vault modification and foreign expansion (Excerpts)

The changes in vault modification practices... result from the foreign expansion into these regions. The spread of a foreign group into any area is bound to result in some similar consequences including shifts in the power structure and distribution of space (i.e. Feinman & Marcus 1998). (With the) conquests of the Huns After AD 200, circular deformation appeared and spread quickly throughout the Eurasian steppes (Fig. 4), eventually becoming the dominant form, replacing occipital modification. Much research has been devoted to circular modification (Khodjaiov 1966; Ginzburg & Trofimova 1972; Tur 1996). Its appearance is probably connected to encounters with the Huns who practiced a pronounced form of circular modification at a very high rate. The Huns traveled from north China to the Central Asian steppes and subsequently to the southern Russian steppes.

Circular modification appeared for the first time in Central Asia in the last centuries BC as an ethnic attribute of the early Huns. The peoples of the southern Russian steppes had not practiced cranial modification during the early Iron Age until the appearance of the Huns. During the first centuries AD, after the Hun invasion of Eurasia, circular forms of modification spread throughout the steppe from the Ural Mountains up to the Danube River.

This distribution parallels the movement of the Huns. Nearly 80% of the steppe population, which consisted of nomadic societies of different ethnicities, came to shape their heads in the same manner soon after the Hun expansion (Tot & Firshtein 1976). People, irrespective of their own genetic origin and local customs, wanted and tried to be similar to the conquerors. These conquerors had become a prestigious group in the steppes and the local populations wanted to emulate them, not only culturally but even physically. Therefore, circular deformation, which had arisen as a concrete element of Hun culture, had, over time, lost its specific ethnic content. The use of cranial vault modification in this case was a response to these changes in society associated with the presence of a new political power.

Discussion (Excerpts)

A strong example is seen in the Eurasian situation where there is the predominant use of cradle deformation. This type of modification is connected, not to attempts to alter physical appearance or to denote ethnic identity, but instead to the traditional nomadic practice of laying children in a rigid cradle. However, it is interesting to speculate that what began as a social and economic behavior could, over time, lead to an understanding of the shaped head as a group identifier and consequently to intentional vault modification. Once the altered head shape is present it can help maintain the physical identity of the group. This particular pattern of cultural evolution may be unique to nomadic peoples and reflect their cultural heritage. The evolution of the practice would be culturally specific and yield some of the differences seen in this comparison (Nomadic lifestyle requires adjustments of the methods and implements. Different people find different methods to achieve the same objective, creating ethnical markers. Türkic people developed mobile yurts, portable self-draining cradles, round-bottom vessels, and defecation sanitary pebbles, for example. Rigid affixing of the child's head in the cradle is a particular method associated with the self-draining cradles. Other peoples, like those belonging to the Indo-European trunk, are marked by absence of these particular methods and implements).

The differences in origin, presence, and type of head shaping between these areas do not obscure the fact that this comparison reveals some cross-cultural regularity in the practice. The occipital-parietal deformation practiced by the population of the Chorasmian state after 500 BC gives a striking example of the use of cranial modification as a signifier of ethnic identity in this area. Nevertheless, that vault modification responded dramatically to the conquests of the Huns indicates that it is susceptible to great social changes.

Circular deformation served initially as an ethnic indicator for the Huns, or at least as a sign of membership or allegiance to this group. Over time, its ethnic meaning changed and it became the common cultural sign of the steppe populations. These were people who had very different ethnic origins yet they adopted this cultural trait as a means of adapting to the new social and political situations that resulted from the Huns' invasion.

Conclusion (Excerpts)

In these examples we can see that altered head shape had a different meaning through changing historical periods and with people of different ethnicities. The social environment plays a large role not only in the decision to shape the head but also in what manner it should be shaped. This practice is, of course, constrained by local customs. In any given situation these local customs will dictate the manner in which head shaping is practiced. However, the larger patterns reflect parallel shifts that result from social changes. The social role of cranial modification and its use as a group identifier allow for a population to use it in a standardized fashion and as such project information about the wearer to the larger group. Moreover, it becomes evident that similar situations and social mechanisms can result in a similar use of vault modification in very different cultures. This has large implications for the numerous societies outside of the Andes and central Asia that had long-standing head shaping practices. This is particularly true for the pre-Columbian cultures of Mesoamerica who have both well-documented histories of foreign interaction and conquest and of cranial modification (Cranial deformation in Mesoamerica and Andes parallels linguistic links, see Contents Amerin Genetics).

Of particular interest is the apparent homogeneity in head shaping that results from state influence. It is probable that this reflects the advantages for the individual of an association with state powers and as such can increase the use of a particular type of head shape in response. Additionally, a large polity could use local ethnic differences for discrimination and to obtain advantages within the region. Cranial vault modification, given its permanence, is easily co-opted to segregate and control populations as seen in the Inka example. Therefore, its responsiveness to the dominant polity may occur regardless of local context. Consequently, interpretations of cranial vault modification need not be considered only as isolated within their particular historical situation and cultural context but rather can manifest in similar ways as the result of monumental shifts in the social environment.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr. Phillip Walker, who encouraged this collaborative venture and made available the space in which it was completed. Additionally, we would like to thank the reviewers Profs K.W. Alt, Mainz, Y. Chistov, St. Petersburg, and V. Tiesler, Merida for their valuable commentary.

REFERENCES (transcribed titles)

Arriaza B (1995) Beyond Death: The Chinchorro Mummies of Ancient Chile. Smithsonian Institution

Press, Washington DC.

Barth F, 1998. Ethnic Groups and Boundaries: The Social

Organization of Culture Difference. Waveland

Press, Prospect Heights, IL.

Blom DE, 1999. Tiwanaku regional interaction and social

identity: a bioarchaeological approach. PhD

dissertation, Anthropology, University of Chicago.

Blom DE, Hallgrimsson B, Keng L,

Lozada MC, Buikstra JE (1998) Tiwanaku 'colonization':

bioarchaeological implications for migration in the Moquegua Valley, Peru. World Archaeol

30 (2):

238-261.

Brain R (1979) The Decorated Body. Harper and Row, New York, de las Casas B (1892) De las

antiquas gentes del Peru. Manuel G Hernandes, Madrid. Cieza de Leo´n P, (1984 [1553]). La

cro´nica del Peru´. Cro´nicas de Ame´rica 4. Historia 16, Madrid. Dembo A, Imbelloni J

(1938) Deformaciones intencionales del cuerpo humano de cara´cter e´tnico. J Anesi,

Buenos Aires. Dingwall EJ (1931) Artificial Cranial Deformation: A Contribution to the

Study of the Ethnic

Mutilations. John Bale, Sons & Danielsson, London. Feinman GM, Marcus J (eds.) (1998)

Archaic States. School of American Research Press, Santa Fe, New

Mexico. Firshtein BV (1974) Materiali k antropologii naselenia epohi bronzi Nizhnego

Povolzhya (Materials on

the bronze age population of the lower Volga region). In: Gohman II (ed) Problemi

etnicheskoi

antropologii i morfologii cheloveka. Leningrad, Nauka, 98—123.

Gershenovitch RS (1929) O

deformatsii zatilka u uzbekskih grudnih detei (The occipital deformation of

Uzbek infants). Trudi Samarkandskogo Universiteta. Etnographia. Vip. 2. Tashkent.

Gerszten PC (1993) An investigation into the practice of cranial deformation among the

pre-Columbian

peoples of northern Chile. Int J Osteoarchaeol 3: 87-98. Ginzburg VV, Trofimova TA (1972)

Paleoantropologia Srednei Asii (Paleoanthropology of Middle Asia).

Nauka, Moscow.

Hoshower LM, Buikstra JE, Goldstein PS, Webster AD (1995) Artificial

cranial deformation at the

Omo M10 site: a Tiwanaku complex from the Moquegua Valley Peru. Latin Am Antiq 6 (2):

145-164.

Imbelloni J (1924-25) Estudios de morfologı´a exacta—Parte III. Deformaciones

intencionales del cra´neo

en Sudame´rica. Rev Mus La Plata Antrop 28: 329–407.

Itina MA, Yablonsky LT (1997) Saki

Nizhnei Syr Dar'i (po materialam mogil'nika Uzhnii Tagisken).

(Saka of the Lower Syr Darya River [Materials from the Southern Tagisken cemetery]).

ROSPAN,

Moscow.

Jones S (1996) Discourses of identity in the interpretation of the past. In:

Graves-Brown P, Jones S,

Gamble C (eds) Cultural Identity and Archaeology. The Construction of European

communities.

Routledge, New York, 62-80.

Kelly M, Kelly RE (1980) Approaches to ethnic identification

in historical archaeology. In: Schuyler RL

(ed) Archaeological Perspectives on Ethnicity in America. Baywood Farmingdale NY,

133-143.

Khodjaiov TK (1966) O prednamerennoi deformatsii golovi u narodov Srednei Asii v

drevnosti

(Premeditated head deformation among ancient Middle Asian populations). Vestnik

Karakalpakskogo

filiala Akademii Nauk 4. Nukus, FAN.

Latcham RE (1937-38) Deformacio´n del cra´neo en la

regio´n de los atacamen˜os y diaguitas, An Mus

Argentino de Ciencias Nat Bernardino Rivadavia 39: 105-124.

Latcham RE (1938) Arqueologı´a de la region Atacamen˜a. Prensas de la Universidad de

Chile, Santiago. Logan MH, Schmittou DA (1995) The origin of tribal styles: an

evolutionary perspective on Plains Indian

art. Rev Anthrop 24: 65-86.

Lozada Cerna MC (1998) The sen˜orio of Chiribaya: a

bio-archaeological study in the osmore drainage of

Southern Peru. PhD dissertation, Anthropology, University of Chicago.

Mannheim B (1991)

The Language of the Inka Since the European Invasion. University of Texas Press,

Austin TX.

Marroquin J (1944) El cra´neo deformado de los antiguos aimaras. Rev Mus Nacional 13:

15—40.

Meskell L (1998) The irresistible body and the seduction of archaeology. In:

Montserrat (ed) Changing

Bodies: Changing Meanings, Studies on the Human Body in Antiquity. Routledge, New York,

139-161.

16

Moseley MM, Feldman RA, Goldstein PS,

Watanabe L (1991) Colonies and conquest: Tiahuanaco and

Huari in Moquegua. In: Isbell WH, McEwan GF (eds) Huari Administrative Structure:

Prehistoric

Monumental Architecture and State Government. Dumbarton Oaks, Washington DC, 121-140.

Moseley ME (1992) The Incas and their Ancestors: The Archaeology of Peru. Thames and

Hudson, New

York. Munizaga J (1969) Deformacio´n craneana intencional en San Pedro de Atacama. In

Actas del Congreso

Nacional de Arqueologı´a Chilena, Museo Arqueolo´gico de La Serena, Chile, 129-134.

Neumann GK (1942) Types of artificial cranial deformation in the eastern United States.

Am Antiq 7:

306-318. Polhemus T (1978) Social Aspects of the Human body: A Reader of Key Texts.

Penguin Books

Harmondsworth, England. Richkov UG (1969) Antropoligia i genetica izolirovannikh

populytsii (Physical anthropology and genetics

of the Pamir's isolated populations). Pamira. MGU, Moscow.

Shilling C (1993) The Body and Social Theory. Theory, Culture and Society. Sage

Publications, London.

Smith C (1997) Body art and archaeological theory. Aust Archaeol

44: 53—54.

Soto-Heim P (1987) Evolucio´n de deformaciones intencionales, tocados y

pra´cticas funerarias en la

prehistoria de Arica, Chile. Chungara 19: 129-213.

Synnott A (1993) The Body Social: Symbolism Self and Society. Routledge, London.

Torres-Rouff

C (2002) Cranial vault modification and ethnicity in middle horizon San Pedro de Atacama

Chile. Curr Anthrop 43/1: 163-171.

Tot TA, Firshtein BV (1976) Antropologicheskie dannie

k voprosu o velikom pereselenii narodov Avari i Sarmati. (Anthropological data on the question about the great migration of populations

Avars and

Sarmatians). Leningrad, Nauka.

Tur SS (1996) K voprosu o proishozhdenii i funktsiyakh

obitchaya kol'tsevoi deformatsii golovi. (To the

question of the origin and functions of circular head deformation). Archeologia,

Antropologia i

Etnographia Sibiri. Barnaul, Moscow. Vifleemskaya ZY (1930) Forma cherepa uzbekskogo

rebenka v svyazi s nekotorimi osobennostyami ego

vospitania (The Uzbek child's skull form in relation to their upbringing). Meditsinskaya

misl

Uzbekistana i Turkmenii. #2-3. Noyabr'- Gekabr'. Tashkent, 31-48. Weiss P (1958)

Osteologı´a cultural: pra´cticas cefa´licas. Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos,

Lima. Wobst MH (1977) Stylistic behavior and information exchange. Anthrop Papers Univ

Michigan 61:

317-342.

Yablonsky LT (1999) Necropoli Drevnego Khorezma (Necropolises of Ancient

Chorasmia). Vostochnaya

Literature, Moscow.

Zhirov EV (1940) Ob iskusstvennoi deformatsii golovi. (Artificial

deformation of the head). In Kratkie

soobsheniz Instituta material 'noi kul' turi. Vip. VIII. AN SSSR, Moscow.