Back

In Russian => PDF

Contents Huns

Contents Alans

Contents Scythians

Roots

Tamgas

Alphabet

Writing

Language

Geography

Archeology

Religion

Coins

Wikipedia

Yu. A. Zuev The Strongest Tribe - Ezgil

Yu. A. Zuev Tamgas of vassal princedoms

Yu. A. Zuev Ancient Türkic social terms

Avar Dateline

Besenyo Dateline

Bulgar Dateline

Huns Dateline

Karluk Dateline

Kimak Dateline

Kipchak Dateline

Kyrgyz Dateline

Sabir Dateline

Seyanto Dateline

Yu. A. Zuev

EARLY TÜRKS: ESSAYS

on HISTORY and IDEOLOGY

Oriental Studies

Institute, Almaty, “Daik-Press”, 2002,

ISBN 9985-441-52-9

Editorial Board: I. N. Tasmagambetov (chairman), M. X. Abuseitova

(deputy chairman), J. G. Baranova, B. A. Kazgulov, B. E. Kumekov,

K. T. Talipov (Kazakhstan), R. G. Mukminova (Uzbekistan),

S. G. Klyashtorny (Russia), A. M. Khazanov (USA), Vincent Furnjo

(France)

This book is his life-long hallmark, Yu. A. Zuev brought to light, or confirmed research of his predecessors, following the development the ancient Hun society into a constellation of scion offshoots, each with its unique history and its place in the evolving world. The Hunnish socio-ideological thought and milieu that defined its society determined the subsequent fates of its descendents and their role in the global history. The 2002 book builds on the studies first published starting from 1957.

Most of the Yu. Zuev book refers to the records and events of the Early Middle Age period, between 160 BC and 850 AD. The events are fairly well known from the Chinese, western and Muslim historians. A comprehensive and detailed history of Early Middle age Türks rising from the ancient Huns still awaits its author.

* * *

Translator's notes and explanations, where embedded in the author's text and not denoted specifically, are shown in blue.

Some special characters may not display correctly, and are either substituted by Latin letters, or duplicated in Latin letters shown in blue: γuən/guan, with Greek “gamma" rendered as “g”, various diacritical “i" rendered as “i”, and “ə" and various diacritical “a" rendered as “a”. Where it appears that simplification infringes on semantic meaning, the author's transcriptions are reproduced more accurately. The author's text can be verified in pdf format reproduction in Russian. Where the author chose to translate place names to Russian, the Translator gives its English translation, for example Türkic “ak" => Russian “beliy" = English “white”.

Page numbers are shown at the beginning of the page. Translator has added some subdivision headings shown in blue.

| From the author | Foreword | 5 |

| Influence of foreign factor in the history of China | 8 | |

| Section 1 | Uechji (Pin. Yuezhi). Yantsai. Usun. Kangju | 13 |

| Uechji (Pin. Yuezhi) | 20 | |

| The term “Usun” | 23 | |

Detour on base and borrowed lexicon | 35 | |

“Ulug" and “Bori" in Türkic lexicon | 35 | |

| Abzoya (Yantsai) | 48 | |

Khavran | 54 | |

| Urbe-Kypchak | 63 | |

Detour about Moon and Hare | 74 | |

| Section 1 (continued) | Kangju | 90 |

Middle Türkic variations | 100 | |

| Kangju in the east | 102 | |

| Section 1 (continued) | Kimeks in the Inner Mongolia | 110 |

| Kimeks on Irtysh. Society | 126 | |

| Section 1 (continued) | Heichetszes | 136 |

| Kongrats | 138 | |

| Shuiytü | 141 | |

| Section 1 (continued) | Türgeshes and Kang | 143 |

| Terms Uchjile and Shato | 145 | |

| Sogdak, Küngü, Tarban | 157 | |

| Detour on the form of family, inheritance and subjectivity | 167 | |

| Section 2 | Türkic Manichaeism | 179 |

| Mani and Manichaeism | 183 | |

| Türkic Ata and Kang (father, ancestor) | 184 | |

| Manichaeism in Jeti-su | 185 | |

| Mani doctrine | 186 | |

| Manichaeism in Sogd | 189 | |

| Manichaean plants, Lion and Chigils | 191 | |

| Manichaeism in Sogd (continued) | 195 | |

| Pearls in Manichaeism | 196 | |

| Chor and Ashtak | 197 | |

| From Qidan to Kitai and Hotyn | 204 | |

| Argu | 205 | |

| Sakal | 205 | |

| Detour about house and housekeepers | 211 | |

| Detour about Tonyukuk | 215 | |

| Ashtaks | 223 | |

| Section 2 (continued) | Kyrgyzes | 236 |

| Digression about the Sun and the Moon | 249 | |

| Kömüls | 252 | |

| House (eb) | 253 | |

| Chik people | 256 | |

| Baiar | 256 | |

| Chigils and Shato | 256 | |

| Appendices | 262 | |

| Chinese records about Suyab | 262 | |

| Ancient Türkic social terminology in the Chinese text of the 8th century | 278 | |

| Rashjd ad-Din “Djami at-tavarih" as a source on early history of Djalairs | 291 | |

| Abbreviations for monuments | 298 | |

| List of Abbreviations | 299 | |

| Bibliography | 301 | |

| Summary | 333 |

5

An idea that come from ancient mythological tradition about the origins of the people in the days of a birth of its genealogical primogenitor had existed in the historical science, and fairly widely continue its existence today.

This idea is faulty in many respects, first of all because it was always created and cultivated by a dominating (dynastic) group, and at best it reflected its own genealogical myth, which at times has no relation to the previous history of a subject people or tribe. Numerous examples illustrate that.

The known version of the

the Mongol genealogical myth about the early history of Chingiz-khan's

Kiyan (Kiyat) dynasty, preserved in the Rashid ad-Din work “Djami

at-tavarih”, contains a complete the final history of the Kimek-Kiyan Oguzes from the river Argun valleys on the eastern

slopes of the Great Khingan range, with ideological tradition

ascending to Uechji (Pinyin Yuezhi).

6

The ideological communes belong to the category of “great conservative forces”. They are less dynamic than ethnic categories, are not identical to them, and can be preserved even with a change in the ethno-linguistical layer. The last factor is a distinctive feature of the people history in the Central Asia and all Eurasian region. The overwhelming majority of early tribal confederations in the Central Asia was poly-ethnical. The dominating position of a large ruling tribe within such confederations made its language prestigious: in it were given orders, it was a language of annual conventions “to count people and cattle”, etc. Generally, it was a language of intertribal communication. Its role was considerably amplified in case of a conquest of such confederation by newcomer people, which in itself creates a situation most favorable to speeding up of this process. But also possible is another outcome: assimilation by a local ethno-linguistical substratum of the newcomer super-stratum, which is giving a new name both to the conquered people, and to its language.

Historical paradoxes

connected with these processes are quite frequentl.

Approximately in the 3rd century BC the queen of the large east -

Iranian Uechji (Pinyin Yuezhi)

tribe joined to her possessions a Tochar (Ch. Dasya) tribe living in the headwaters of the river

Huanghe. Since then the “queen’s" tribe Uechji in the Chinese

chronicles began to be called Da-Uechji ("Great Uechji”), and

the Dasya-Tochars began to be called Syao-Uechji ("Lesser

Uechji”). Together, they were simply called Uechji. The scholar and

translator of the 5th century monk Kumaradjiva, translating Buddhist

texts into Chinese language, translated the word

Tochar as

Chinese Uechji. In the middle of the 2nd century BC Uechji

become a main force of the so-called “storm of the Bactria”. In

turn, the ancient authors inform that the conquerors of Bactria were

tribes Ases and

Tochars. Bactria

began to be called (by Chinese) Dasya country, i. e.

Tocharistan, and the

language of the inhabitants of that country began to be called “Tocharian”. The known orientalist, Danish scientist Stan Konov

even named one of his works “Was “Tocharian" language really Tocharian?”.

7

The Tochars of the Kidan (Kitan/Khitan) state in the Manchuria territory spoke proto-Mongolian language, the medieval Tochars (Dügers) in the future Turkmenia spoke Oguz, and the Tochars (Digors) in the Northern Caucasus spoke Alanian, i. e. in Sogdian-Türkic per Biruni. Meanwhile, their ideological traditions in many respects remained similar.

This book is discussing continuity of ideological traditions.

Chinese records about ancient Türkic genealogical legends document the previous history of the dynastic Ashina tribe (Hot. -Sak. -asseina “dark blue”, "blue”), which became dynasties in the First and Second Türkic Kaganates. Neither the name of the dynastic tribe, nor the names of the historical founders of the Türkic Kaganate, Bumyn and Eshtemi, are Türkic.

I tried for years to explain this phenomenon by tabooing of Türkic sacral names, and their replacement with foreign language equivalents. This outwardly reasonable speculative conclusion was published a number of times, it did not bring printed or verbal disagreements, but yet no specific confirmation was found in written sources.

"Pure" ethnoses do not exist. Turning to the early history of many peoples demonstrates that.

Such fates are widely known. The Frenchmen received their name

from the German tribe of Francs. The founders of Russian state,

Scandinavians-Vikings (Normans) created Rürik dynasty in Kyiv and

gave eastern Slavs a Scandinavian name Rus. The Middle Kingdom (Chjun

go) also did not miss such a fortune , it was known, for example,

under non-Chinese names of Tabgach and Kitai (proto-Mongolian,

Cathay/Khithanian). For the Middle Kingdom, whose role in the

history of the world culture in general, and the peoples of Eurasia

in particular, is well-known, this phenomenon is especially typical.

8

Influence of foreign factor in the history of China.

The founders and dynasts of the China Chjou (Pinyin Zhou) state (11th century BC - 256 BC) are foreign tribes, the Han dynasty (Former Chjao, Pin. Han Zhao, 304-328) was established by the northern nomadic tribe Sünnu, the Later Chjao (Pin. Later Zhao) dynasty (319-325) was established by the Tsiantszüy tribes, related to the Central Asian Kang, the dynasty of the Western Tsin (Pin. Western Jin) state (388-431) was Syanbi (Pin. Xianbei) (their language was proto-Türkic and proto-Mongolian), and the founders of the dynasty and state Former Yan (333-370) belonged to the tribe Mujun (from Amur and Manchuria). They also were dynasts in the Western Yan (384-394) and Southern Yan (398-410) states. The Southern Lian (Pin. Liang) state (397-414) was established by the Syanbi (Pin. Xianbei) from the Tufa tribe ("braid-weavers”, whose braids was considered to be a ladder to the Sky), and the Sya (Pin. Xia) state (407-431) was established by the Sünnu (Huns), the dynasts of the State of Dai (Northern Wei, 386-530) were Toba (Pin. Tuoba) Syanbi (Pin. Xianbei) (Tr. Tabgach), the dynasty Northern Tsi (Pin. Qi) (550-577) was Bohai (tribes of Far East), the dynasty of the state Later Tan (Pin. Tang) (923-956) was established by the Shato Türks (their western Chigil tribes), the state Liao (907-1125) was Kidanian (Pin. Khitanian), Tszin (Pin. Jin) (1115-1234) was Chjurdjen (Pin. Jurchen) state. The Yuan dynasty (1260-1404) was Mongolian, and Tsin (Pin. Qing) (1644-1911) was Manchurian.

The testaments of similar nature doubtlessly have oral-historiographical (for example, genealogy-shejre) and literary significance, they are unique, but they cannot serve as unique reference points for ethnological research. In greater measure they are important for study of the process of emergence of statehood in different areas of the Central Asia.

The ethnological research have and apply a number of other

methods. Unfortunately, each of them is imperfect, is not also developed the methodology

of the historical-ethnological sciences as a whole.

9

The old Marxist definitions for the most key categories turned out to be unsound, and consequently were rejected, and new are not formulated yet. They are necessary for understanding such complex historical, ethnogenetic and ecological-geographical phenomenon as the Central Asian massive. Inextricably connected concepts of polito-genesis, ethnogenesis, culture-genesis, ideo-genesis are not always filled with specific contents and needed criteria. What are the unclear reasons for similarity (down to terminological) of the polyglot mythological systems separated by space and time. What is the chronological ceiling for the inertia of ideological continuity? Where passes a divide between the stages in the historical process and convergence?

Even a small portion of these questions can't be answered within a framework of one, even a cleverest book, because the available written material is insignificantly small or inaccessible for the different reasons.

In ancient annals and works at times are externally wasteful

phrases and

messages without direct relation to the text and seemingly without

any significance. But a merciless censorship of millenniums does not

allow anything insignificant to pass through its restrictive sieve.

For example, Mahmud Kashgari tells a story, popular during his time

(11th century), about a rain cloud beyond the Hodjent river, that

pored streams of water, and created mud which became impassable for

the Alexander the Great army. The legendary conqueror perplexedly

exclaimed: “What kind of mud is that? We cannot get out of it!”, and

ordered to erect there a building where Chigils settled down.

On a closer examination it turns out that that that is a

mnemonic-coded information about a first stage in the spread of the

Manichaean religions in the Türkic world. Rising to the Light (the

Country of Gods), the pure Manichaean soul is rinsed in a rain

cloud, which washes off all terrestrial sin, and together with the

rain they fall down and form mud. The dirt matter, a mixture of

Light and Darkness, is that substance of which a terrestrial

creature is made, and the “building" is a “school”, a prayer hall of young

Manichaean monks.

10

A part of such material, in logical sequence that makes sense for me, is described in this book.

As a substrate (base), is chosen historical material accessible from written sources (mostly Chinese, they collected a systematic record of historical information about most ancient peoples in the north and west from the Great Chinese Wall ) about tribal “states”, Uechji, Usun and Kangju confederations, collected in the 1st section of the book.

As transpired during years of research, Uechji and Usuns were not two different “state" confederations, but one from the beginning, with two ethnically different and opposing halves of a uniform cosmo-ideological complex “Sun - Moon”. It was a gynocratic state of a lunar clan Uechji (Uti, Ati, Asi), based on the maternal form of the community with a corresponding principle of inheritance, including dynastic. The crisis of this form has caused separation of the Usuns (As-mans) in the transition to the patriarchal form of the family. The gynocratic form of community was a “brother family" with the inheritance principle “senior brother - younger brother (from the same mother) - nephew (from a female line, the son of the senior brother)”, i. e. the principle of combining in the inheritance of the male and female lines.

More detailed description of this form of family is given in the paragraph “Sogdak, Küngü, Tarban”, where is described a sharp crisis created by attempt to transition to solely patriarchal (Kagan) rule, which caused a civil war in Eastern Türkic Kaganate in the beginning of the 8th century. It also was a main reason for creation of opposing in their contents and objective large ancient Türkic runiform inscriptions in Mongolia.

The pattern of the text and contents of the sections are driven by

the idea of evident ideological continuity, traceable from

the first written records about

Uechji and Kangju tribes (2nd

century BC). The sections about tribes or confederations which are

ideological heirs were limited to a problem ideo-genesis research as

a major components of culture genesis, they cannot be mistaken for

ethnogenesis. The are only a study material for ethnogenetical studies.

11

The main actors of the Uechji mythology, with partial preservation of the names, are encountered in the pantheons of Yantsai (Alans/Abzoya), Kypchaks, Türks-Oguzes and Türks-Ashtaks. The likely ideological successors of the Kangju (Kangha, Küngü, Kang, etc. ) “state"-confederation are the Kangits, Hanga-kishi, Azkishi, Imeks, Kangly. The substrate ethnopolitical base of the Türgesh Kaganate was Uechji-Kangju. The Türgesh Kaganate was a new state, and not a continuation of the Western Türkic Kaganate history.

Such patterning of the material, not by a political, ethnic or another attribute, and only by a principle of ideological continuity, is not an end in itself and not a pursuit of originality, but a way to establish channels of ideological continuity from the last centuries B. C. to the new times.

The second section of installments is named “Türkic Manichaeism”, I examine it as systematic compilation of material about introduction and spread of Manichaean world “religion of Light" in the Türkic Steppe in the 4th-10th centuries. Comparative ease and painless adoption of this theology clearly shows the important factor that it absorbed in its credo all rational contents of the local cults. In a number of cases the Manichaean religion benefited from formal similarity of the local cult with the Manichaean theology. For example, the originally Uechji views about Moon, Milky Way (Tree of Life) and Dragon were temptingly beneficial for the conclusion about their similarity with the Manichaean symbols.

At the beginning, Manichaean preachers

were trading Sogdians, the main operators on the Great Silk Road,

which numerous routes covered the whole continent, up to Pacific

Ocean coast. Trade aided religious preaching, and religious preaching became a reliable

aide for traders.

12

Adoption of Manichaeism by the leading layer of the majority of Türkic tribes meant their joining the economic and cultural connections of the continent.

Some observations of this book have been published, they were noted in scientific and periodical publications.

The scientist of the NAN Institute of Oriental Studies K. U. Torlanbaeva rendered a great assistance gathering literature for the theme, in textual work, and by writing some sections of the book.

Highly skilled technical participation in the preparation of the manuscript for printing was done by the staff of the publishing house “Daik-Press”.

The initiative in composing this book belongs to the director of NAN Institute of Oriental Studies, professor Ì. X. Abuseitova, without whose assistance it could not be published.

Taking an opportunity, I bring my sincere gratitude and gratefulness. I shall be especially grateful to the reader who, taking this small book, will read it to last page without thinking that he have wasted his time.

Technical note. This book is based on the records contained in the Chinese written sources. Index C in the book designates the large Chinese-Russian dictionary in Russian graphic system in four volumes, composed by a collective of Sinologists lead by and edited by professor I. M. Oshanin, published in Moscow in 1983-1984. The numbers following it are the of dictionary nest numbers. They are followed by a transcription of modern phonics of the hieroglyphs from that dictionary. The Latin letters in brackets give their Middle Chinese phonics following Karlgren Â. Grammata Serica Recensa. Reprinted from the Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities, Bulletin 29. Stockholm, 1957.

UECHJI (Pin. YUEZHI), YANTSAI, USUN, KANGJU

Prior to the end of the 3rd century BC, the dominating force in the

eastern part of Eurasia was the “state" confederation of

nomadic and semi-nomadic tribes dominated by Uechji (Pinyin Yuezhi)

tribe

. The borders of this confederation can be outlined only

conditionally. From the vague records of the later time, its

southeast limits were at the left bank of the river Huang He from

the headwaters before the northern bend to the south. The border

further went to the north, covering western and eastern slopes of

the Great Khingan. At the northern extremity it turned to the west,

from Northern Mongolia and Southern Baikal area to the Sayano-Altai

mountains. It included tribes of different origin, various

languages and anthropological type, and non-uniform cultural and

economic conditions. The native territories of the Uechji were lands from the Nan Shans

mountains in the south to the Altai in the north.

14

In Altai, the memory of Uechjies (Pinyin Yuezhi) survived as a group of Pazyryk kurgans with fabulous funeral inventory, which remains for decades a research subject for different scientific specialties. Chronologically, the first of them are dated by the 5th century BC (A Yu. Alekseev et al. C14 dating testifies to much earlier period - Translator's Note). The arrival of Uechjies in this region, according to linguists, belongs to the period not later than 7th-6th centuries BC. Other scientists, deeming them Tochars and from the archaism of the many elements in the monument language of the Tocharian writings (end of the 1st millennium AD) in the Eastern Turkestan, are inclined to date the beginning of their movement from the Asia Minor to the east by the 2nd millennium BC. The presence of Tochars explains the sharp change in quality in the art of Bronze Epoch, and introduction of wheeled transport in China during the In epoch (13th-11th centuries BC). The presence of Tochars also explains the arrival in China of a foreign goddess cult “Mother-queen of the West" (Ch. Si-van-mu), who lived on the top of the Kuenlun mountains.

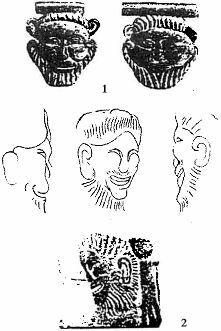

Anthropologically (Fig. 1), the Pazyrian Uechjies were predominantly Europoids. Central Asian Mongoloids were a minority. The Sünnu (Huns) tribes, thought of as Mongoloid racial type, started to consolidate and threaten the borders of China, being in political dependence from Uechji. How this dependence was expressed is not known. The annals only inform about a system of hostages from the dependent tribes at the horde of the Uechji ruler. Such hostage was Maodun, a son of the first Sünnu tribal ruler Touman.

Fig. 1. Sculpture of young Uechji

Halchayan (Uzbekistan)

Chronicler explains the reason for sending Maodun to Uechji: Touman-shanyu did not want his son Maodun to inherit him, and possess the throne of the Shanyu supreme ruler. He wanted another son from another wife, whom he loved, to be his successor. To frastrate the Maodun's claims to the throne, he send him to Uechji, and immediately declared a war, certain that his heir son will be killed. During a battle Maodun came back to the Sünnu, killed his father, and declared himself a Shanyu [Sima Qian, ch. 110, p. 1032-1033, f. 7b-8à, Taskin, 1968, p. 38].

Only this text

tells about Touman attack against

Uechji, but it could

have never been recorded. It is also known that to create a visible

legitimacy for his right to the throne, Maodun, after the murder of

his father, married his “mothers”, i. e. Touman wives [Sima Qian,

ch. 99, p. 965, f. 4à]. The sequence of causes and effects in the

succession acts raises doubts, because it is more suitable for a

minstrel than for an annalistic report of these events. The essence

of the events is that the son had no right to direct succession to

his father by taking over the supreme throne. “Between Huns, -

wrote N. Ya. Bichurin, - the throne was predominantly transferred to the first

brothers, and to the nephews from the first brothers" [Bichurin, 1, p.

99, note 2].

15

Only in the 201 BC Maodun-shanyu, after victories over the “eastern barbarians" (Dunhu, Pin. Dongye/Dongyi), dared “to attack Uechji in the west and to expel them”. Under Maodun, the Sünnu became unprecedentedly strong, subdued all “northern barbarians”, and formed a state in the south, “equal in strength to the Middle State”. In 25 years (176 BC) Maodun proudly informed emperor Han: ”. . . Due to the favor of the Sky, the commanders and soldiers were in sound condition, and the horses were strong, which allowed me to destroy Uechji, who were exterminated or surrendered. I [also] pacified Loulan, Usun (Pin. Wusun), Hutsze and other 26 neighboring possessions, which all began to belong to Sünnu" [Sima Qian, ch. 110, p. 1035-1036, f. 13b-14à, Taskin, 1968, p. 43]. In 127 years (in 49 BC) the annalistic description about conclusion of an oath declaration between Sünnu and Han attributed this victory to Laoshan: “Using the skull of the defeated by Laoshan-shanyu Uechji ruler as a bowl, they drunk wine as a token of conclusion of alliance bonded by blood" [Ban Gu, ch. 946, p. 1131, f. 6a-b, Taskin, 1973, p. 38].

The horse bridle of the Uechji soldier

from Pazyryk was decorated with ornaments embossed with

images of fallen enemies, the Sünnu Mongoloids (Fig. 2). Now the Sünnu drank from a skull of the killed Uechji leader the oath wine

with blood of a sacrificial white horse

mixed with a gold spoon [Klyashtorny, Savinov, 1998, p. 169-171]. After that, there was

no Uechji “empire" any more.

16

Fig. 2. Sünnu

images

1

- Models of human heads on Pazyryk bridle

2 - Sünnu

images of from funeral

complex Ho Tsüibin (Southern Altai).

17

Probably, the tragical defeat of those years should be viewed as a reason for Uechji tribes mass migration to the west. But the migration was not universal. A significant part of the Uechji remained in their former places in their main territory and in the northern belt, but in reference to them the ethnonym Uechji was not mentioned any more.

For Sünnu, the defeat and conquest of the nomadic neighbor did not mean occupation of the new territory, but an one time robbery (first of all cattle and women), and establishment of tribute relations, with inclusion of the defeated army in their army, a presence of the defeated leader at the annual assembly for “accounting of people and cattle”, and acceptance of the politonym Sünnu. In case of external danger, the last could serve as a reliable shield, but it is a barrier for a modern researcher, who could presume as Sünnic all ethnocultural complexes from Khingan to Nanshan. We shall give a telling example. In 7 BC imperial court concocted a plan: under a far-fetched pretext of “border alignment" to capture from Sünnu all the Uechji fertile lands with a center in Chan-an. Shanuy responded: “On these lands lives a [borderguard] ruler Outo from a Ven (Hvar) tribe, and I do not know neither their setting, nor what they produce. Let me send a courier to find out about it”. After receiving report, he responded to the Hans: “I learned from the [borderguard] ruler Outo of the tribe Hvar (Ch. Ven) that all Sünnu (i. e Uechji) princes who live in the west make yurts and carts out of the wood from the mountains in these lands, and these are the lands of his fathers, and he does not dare to lose them" [Ban Gu, ch. 94b, p. 1134, f. 136-435, f. 14à, compare Taskin, 1973, p. 46].

The quoted lines give sufficient idea about the vassalage relations. In this case they are limited to the “outo" concept, meaning a duty to be a “sentry" and a barrier on the frontier, and a participation in the military operations of the suzerain. In the eyes of the Shanyues, the Uechji were and remained a “small state on the western border of Sünnu”.

Chjan Tsian (aka Zhang Qian). The union was a main military threat to the Han empire, and the imperial court relentlessly searched for an ally to fight against Sünnu. In this struggle it viewed Uechji as potential allies. Chjan Tsian was sent with an intent to conclude a union with them, he left Lunsi on the eastern edge of the Gansu province, but he went not to the west, but to the north. The supreme ruler Tszjunchen-shanyu, interrogating the immediately captured Han ambassador, told him: “Uechji are north of us. How can Han send an ambassador through our country? If we wanted to send a currier to the Üe (far south in relation to Han), would Han allow us to do that?" [Ban Gu, ch. 61, p. 749, f. 16, Kryukov, 1988, p. 240]. Certainly, this is a Chinese interpretation of interrogation re-told by Chjan Tsian, but its sense is unequivocal: he went to the north.

Chjan Tsian stayed in captivity for10 years. He

settled, married and had a son, but did not forget the purpose of

his trip, and saved the ambassadorial bunchuk

(symbol of power, a staff with horse hair on the top -

Translator's Note). When he had a chance, he fled, and continued

his trip started a decade ago. His route went by the Northern road

through Terekdavan pass to Fergana

valley (Ch. Davan, Daiuan), and the to Kangh (Ch. Kangju) and, at

last, to Bactria, where at that time already lived the escaped

Uechji. He already knew

their history,

learned during his life with the Sünnu. This knowledge reflected

the Sünnu vision of the past, a vision of the victor. Returning

home after twelve - thirteen years, he reported in detail about

everything he had seen, and about the unwillingness of the Middle Asian Uechji

to oppose Sünnu. About the Usun state, which was away from his route, he

said: “Living among Sünnu, your servant

heard that Usun king is called Hunmo. The father of Hunmo, by a name Nandou-mi,

in the beginning lived together with Great Uechji

between the Tsilyan (Qilian) mountains and Dunhuan, they constituted a small state.

18

Great

Uechji attacked and killed Nandou-mi

and captured his lands, and his people fled to Sünnu. His son Hunmo was just born, and tutor Butszju-sihou fled with a baby in his hands.

He laid him in

the grass and went to search for food. Upon return, he saw that a she-wolf feeds [the baby] with milk, and the raven with meat

in its beak flies beside. Deciding that [the boy] is divine, he took him and returned to Sünnu.

has grown fond [of Hunmo], and brought him up. When [Hunmo] has grown up, Shanuy gave him the people of his father, and sent him to lead

an army.

A few times [Hunmo] was successful. At that time the Great Uechji, already

defeated by Sünnu [armies], attacked in the west the

king [of the people] Se (Saka) which fled south and migrated to the far

away lands. Uechji began to live on

his lands. Hunmo was in a prime of life, and asked for Shanyu

permission to revenge his father. And then in the west he attacked and

defeated Great Uechji. The Great Uechji again fled to the west and

migrated to the Dasya (Bactria) lands. Hunmo seized his people and settled there,

[then] his army grew. And when Shanyu died, he did not want to serve

the Sünnu [shanyues] dynasty any more. Sünnu sent an army

against Usuns, but was unsuccessful: thinking that he is divine, the army left. Nowadays,

the Shanyu has new difficulties in

relations with the Han, and the [former] Hunmo lands are empty.

The barbarians dream about returning to their former lands, and, besides,

are eager for the Han's goods. If to take advantage of the situation, ingratiate Usuns with

generous presents, we will convince them to move east to resettle on the

former lands of Hunmo. [After that] we shall send a princess, and establish brotherly relations. We

would begin patronizing them, and they will

obey. Doing that, we shall chop off the right hand (i. e. the right wing, the

Western territory) of Sünnu “[Ban Gu, ch. 61, p. 750, f. 4à-í,

Kryukov,

1988, p. 232, 227-228].

19

The text of the Biography of Chjan Tsian is a fundament for the earliest stage of the Uechji -Usun relations. This Biography is placed in the Chapter 61 of the “History of Han dynasty”, it formed a canvas for reconstruction of the Narration about Davan in the “Historical notes”, lost soon after the death of Sima Qian [Kryukov, 1988, p. 229-230]. Reconstruction of the lost text was made with errors and changes that altered their meaning. For example, the words “Great Uechji attacked and killed Nandou-mi" were changed to “Sünnu attacked and killed his father" [Sima Qian, ch. 123, p. 1140, f. 9b]. This replacement, as will be shown, completely distorts the picture of internal relations in the lunar-solar rule of the Uechji and Usun state. The reader without access to the Chinese original is limited to the distorted text [see Bichurin, 2, p. 155], and thinks that the subject is an attack of Sünnu against Usuns. The words “Hunmo's father by the name Nandou-mi in the beginning (or: “initially”, "in the root”, ch. ben) lived together with Great Uechji between Tsilyan (Qilian) mountains and Dunhuan, they constituted a small state" are changed unrecognizably: “Father of [this] Hunmo was [a leader] of a small state on the western border of Sünnu “(compare Bichurin: “Father of this Gunmo had a small possession on Hunnu western limits”). The words “Butszju-sihou fled with a baby in his hands. He laid him in the grass and went to search for food. Upon return, he saw that a she-wolf feeds [the baby] with milk, and the raven with meat in its beak flies beside. " are changed to: “Hunmo stopped in a field. The raven flew above him with meat in its beak, she-wolf fed him with its milk" (compare Bichurin: “Gunmo, just born, was abandoned in a field. Birds pecked insects from his body, she-wolf came to feed him with its milk”).

There is also an obvious error in the text of the legend, because

of the Sünnu being a source of the story. The military actions

of the listless Usuns, with only one remaining representative brought up at the Shanyu

court, are credited with exaggerated great role in the events that

cardinally changed ethno-political map of a huge region. D. Sinor, who investigated this story, wrote: “Studying Usun history probably presents more problems than solutions" [Sinor, 1982, p. 239]. Nevertheless,

the story of Chjan Tsian can be viewed as a valuable and the only source

of non-Han origin for the study of the dim period in the history of Central Asia.

20

Uechji

Chinese transcription Ñ5845, 11435 Uechji (<*ngiwat-tie) transcribes the sound of the the foreign term *uti/oti/*ati. It also has a semantic sense. The hieroglyph Ñ5845 jue means “Moon, female force In, wife, queen”. The term Uechji means “clan of the Moon”. Such understanding of hieroglyphs in the transcription of Uechji is confirmed by a constant epithet “Moon" (Sanskrit candra, canda, Iranian mah) in the name of the king Kanishka of the Uechji - Kushan state [Maenchen-Helfen, 1945, p. 80]. One of the earlier transcriptions is Ñ4056, 11435 nüchji (<ngiu-tie <*uti ~*oti) “clan of the bull”, i. e. “clan of the bicorn (rising) moon, crescent”. Such interpretation is justified by the words from Iranian “Vendidad" (Ch. 21): “Ascend, rise crescent, - you, which gestate a bull”.

A part of this tribe in the northeastern corner of Ordos, and further northeast from it, had a name Üychji (< ngiou-tie < *uti) “clan of greenstone/jasper”, a symbol of the Moon. These hieroglyphic versions reflect pronunciation uti and contain information about the main ethnographic feature of this tribe: it is a “clan of the Moon”, i. e. clan of Queen-Woman. The Uechji go name in the sources means not only the “Uechji state”, but also the “Queen-Woman state”, ginetocratic state. In this light, the words of the chronicler are indicative: “When the king of Great Uechji was killed by the Huses (Sünnu, 176 BC), his spouse became a queen. She conquered Dasya (Bactria) and ruled it" [Ban Gu, ch. 61, p. 749, f. 1b-2à].

The native lands of Uechji were “between Tsilyan (Qilian) mountains and Dunhuan”. "Lianchjou, Ganjou, Sujou, Guachjou, Shachjou and other districts are the Uechji state lands”, explained one of

the comments [Sima Qian, ch. 123, p. 1136, f. 1à]. On their southeast

border was Ñ8414, 10754 Dasya (<*da-γa) area. The hieroglyph Ñ10754 in

the toponym could reflect hara [Gertsenberg, 1981, p. 237],

this allows reconstruction of the reading as dahara. This

name was subsequently transferred on Bactria, conquered by Uechji tribes, as Tocharistan

(Ch. Dasya).

21

In the 10th century in these territories was created a Tangut state Si Sya, thought of as a restored state of the ancient Dasya. It was called: Bo Gao Dasya go “White and High state Dasya (Tochar)" [Kychanov, 1968, p. 54-55]. Hence, in the transcription of Dasya is justified to see the initial Tochar. Ptolemy (VI, 16, here and below following Stevenson, 1932) in the description of a trade road mentions a tribe Tagur and a city Togara at the end of a trade road to the country of Sers [Roerich, 1963, p. 121-122], probably identical with the Dasya district [Ban Gu, ch. 28b, p. 406, f. (à)]. It was located on the homonymous river, a tributary of Taohe, flowing into Huang He. This area was a part of the Uechji state [Lu Imou, 1924, Huan Venbi, 1950]. In the east it was reflected in the binomial ethnonym Ottorocora (<*ot+torcora, compare Khot. -Sak. Taudakara, Tib. Thod-kar), mentioned in the same part of the Ptolemy work. Reflecting the process of Uechji migration to the west, in the Chapter XII (Sogdiana. The seventh map of Asia), in northern part of the Yaksart section (according to S. P. Tolstov, it is Kuvandarya, a left tributary of Syr-Darya) he places a tribe Yati and Takhor (Tachori), and in the Chapter XI (Bactriana. The seventh map of Asia) he places “Tochars (Tochari) - a large people" (Ch. Dasya). The problem of equating Bactrian Dasya-Tochars was resolved by G. Haloun [Haloun, 1937, p. 290].

Strabo (XI, VII, 21) wrote that Bactria was captured by the Ases, Pasians (i. e. Ases or Asians), Tochors and

Sakarauls (i. e. Sakarauks) tribes, who came from Yaksart. Pompeus Trogus

(1st century BC) in the extractions of Justin (1st century AD) names

the conquerors of Bactria and Sogdiana Sa(ka)rauks and Asians,

belonging to the Scythian tribes. The Asians were “kings of

Tochars" (reges Thocarorum Asiani) [by: Umnyakov, 1940, p.

182-183]. The Scythian term “Asian” finds

correspondence in the “Atian” of Pliny, who also knew the tribe of Attacori west from Funs

(Huns) and Focars (Tochars) [Piankov, 1988, p. 192].

22

Advising on plausibility of transposition -t-//-s in the words Asian/Atian, prof. V. I. Abaev wrote: “In the Ossetic the Iranian “s' corresponds with “t": forot “axe" (Ir. *parasu-), roton “rope" (Ir. *rasana) and talm, a name of a tree (Ir. *salmi-). So, the transposition as-//at- for ancient Iranian period is admissible and logical”. This allows to deem as cequivalent the terms Ot-/At-/As-/Asi, and in the Atian/Asian to see a plural form of Ati, Asi. The Chinese appelation Uechji corresponded with Uttorocora/Attocar, it was common for Ases and Tochars in the east and in the west.

The term Az continued its existence in the Türgesh time. Tamga as a bow

![]() (symbol of

a rising moon) is found on the coins found in the excavations in the Chu

river valley [Kyzlasov, 1960, p. 196, 209]. Precisely the same tamga

have the Kirgiz tribes Azyk and Bugu ("Bull”). It was called

jaa-tamga “bow-tamga" [Abramzon, 1971, p. 39].

(symbol of

a rising moon) is found on the coins found in the excavations in the Chu

river valley [Kyzlasov, 1960, p. 196, 209]. Precisely the same tamga

have the Kirgiz tribes Azyk and Bugu ("Bull”). It was called

jaa-tamga “bow-tamga" [Abramzon, 1971, p. 39].

We do not have direct reports about the throne succession system,

reflecting the status of family and community in the Uechji

union. Only a record exists that among the small Uechji the names of

the tribes are

given by the names of the mothers [Fan E, ch. 87, p. 1305, f. 39b].

However, a constant presence in the dynastic co-rule of the “clan of the

Sun-Raven" shows that the family unit ceased to be solely

matriarchal, it was in the first phase in the transition to the

patriarchal period, when in the head of the family was a queen, and her spouse

was not an “Olympic hero" from the outside, but a representative of the firmly

established paternal (solar-royal) clan.

23

With a large degree of conjecture such community condition can be defined as “sisterly”, where the inheritance is passed by the line “matron - younger sister - niece (daughter of matron)" with a participation of a traditional fatherly clan by the same scheme, but on the second plane. This scheme is reconstructed as some “anti-similarity" of the following and more documented phase, which the author of these lines (after Ü. V. Bromley) calls “brotherly family”, a direct progenitor of the patriarchal family described below. Development of productive forces and escalating (especially military) role of the man in a society and family resulted that the fatherly clan structures became confined by gynocratic limits. The conflict was inevitable. It can be thought that its result was the murder of Nandou-mi and separation of the Asmans (Usun). With the same hieroglyphs “Han shu" spelled the name of the Nandou-mi state on the river Gilgit (a tributary of Indus in Northern Pakistan), which was bordering in the west with the Great Uechji of the Bactria, hardly a simple coincidence [Ban Gu, ch. 96à, p. 1160, f. 10à, Malyavkin, 1989, p. 95-96, 294].

The term “Usun”

2

millenniums ago “Usun” sounded *ah-sman < *asman, and the

“Asman” was an Iranian word meaning “sky”, the modern phonetics of

the “Usun” is a modern pronunciation of the hieroglyphs Ñ7696,

4412 烏孫. The annals also contain the Chinese translation

of this term. Around 107 BC, a Han emperor sent to the Usun (Asman)

country a princess to

marry the Usun ruler. She was young, and the ruler was old.

They met once-twice a year, she was bored, and she composed a song

that began with the words: “Gave my relatives me out to the Sky (Tian) country" [Ban Gu,

ch. 966, p. 1167, f.

3a]. And a second attestation, in China the Usun horses (Ch. Usun ma) were

called heavenly horses (Ch. Tian ma) [Sima Qian, ch. 123, p. 1142,

f. 12à, Tszyan Botszan, et al. Lidai. . . , I, p. 42]. Ptolemy (177 AD) knew a tribe with such

name (Asman). During his time it was located to the east from

Ra-Itil-Volga (VI, 14).

24

The hieroglyphic etymology of “u-sun”, noted by P. Daffina [Daffina, 1969, p. 145, note 6], has a meaning “Descendants of Raven”. The meaning of these hieroglyphs is significant, the mythological image of the Raven is far from trivial. In ancient India raven was held as a senior brother of Garuda, the Eagle. As the story goes, two birdie embryos grew for some thousands years in a belly of one of the gods (different names are mentioned). Only an eternal night existed then, and the day had yet to be created. One of the embryos eagerly dreamed about meeting a first sunrise, and begged the god to let him out from the belly, even though till its birth remained another thousand years. And the god took pity. And the embryo left underdeveloped, and in the rays of the rising morning Sun its plumage looked red. And he was named: Aruna, which means Red. It was a Raven. He became a driver in the Sun chariot, and a symbol of the morning dawn. And the other embryo left in time, one thousand years after the Raven, and went at once in search for bloody food. It was Eagle, he was named Garuda. He became a king of birds, like Indra is a king of all gods [Erman, Temkin, 1957, p. 54-56, 209].

In ancient China the Raven U or Chi-u ("Red Raven ”)was

a personification of the sun. According to the most ancient myths,

in the beginning ten suns were in the Sky, and the heat was crushing. To get

rid of it, was called a Hunter. The hunter Hou-i came to a plaza,

pulled a bow, and sent a

white arrow into the flaming ball in the Sky. In an instant the ball burst and

fell down, shedding gold feathers. Something sparkling fell to the ground.

People run up and saw a huge Gold raven, pierced with the arrow.

It was one of the Suns [Yuan Ke, 1987, p. 143, Yanshina, 1984, p.

43]. The paleo-Asian peoples of Amur, Indians of Northern America, Chukchis,

Sakha Yakuts, etc. connected it with light and

fire [Meletinsky, 1992, p. 245-247]. The myth about

connection of the Raven with the Sun was known to the

Crimean Tatars. “The Raven, so big that when he flies, sun eclipse

happens, is marrying the younger daughter of king. When her younger brother needed to find

a daughter of the Sun, the

Raven collected his subject birds, and one of them helped

the prince to find the daughter of the Sun “[Potanin, 1894, p. 725,

Dyrenkova, 1929, p. 125].

25

The documents of the 17th-18th centuries from Shoria recorded ulus Kyzyl Karga - “Red Raven”. Among the Shors was a seok (clan) Kyzyl Karga. Some of them in the past migrated to the valleys Esi and Tei, separating into seoks Sug- Karga (Water Karga) and Tag-Karga (Mountain Karga). During separation, they disputed the division of eagle feathers, instead of raven feathers, [Potapov, 1969, p. 132, Kimeev, 1986, p. 48]. In an episode from the Mongolian annals, a Kongrat Dai-Sechen addresses his brother-in-law Kiyat-Bordjigin Esukei: “Last night I saw in a dream that instead of a krechet (hawk) I hold a raven, representing a tamga (sulde) of the clan Kiot (Kiyat), from the Bordjigin family" [Gomboev, 1858, p. 124, Abramzon, 1971, p. 356].

In 647 Western Türkic Kagan from the Ashina tribe presented to the Tan emperor a Golden Raven as a gift. They carved a “feathery creature out of wood and plated it with gold" [Van Tsinjo, ch. 970, p. 1140, f. 12à]. Arrival in China of certain raven-like birds heralded an invasion of Türks. This bird was contemptuously called “hoofcie" (Syrrhapta paradoxus) or “Türkic birdie”. But the respective article in “Tai-pin guan tszi" encyclopedia is called “Great Raven" [Li Fan, ch. . 139, p. 1005]. Obviously, behind the everyday name was hidden symbolism of entirely different type.

In the epos “Kitab-i dedem Korkut”, all royal Oguzes traced their descent from a mythical bird Tulu/Dulu [Bartold, 1962]. The “Gold (Kagan’s)" clan of the ancient Türkic dynastic tribe Ashina (< Hot. -Sak. ashsheina “blue”, "dark blue”)was called Shar-Duly (< Middle Persian zarr duli “Golden bird Duli”, "Golden/Red Raven”). In that clan was born prince Kül-Tegin. In the glabella part of his sculpture in the Husho-Tsaidam enclave (Northern Mongolia) his headdress is embroidered with a bird with wings spread like an eagle [Sher, 1966, p. 19, Hayashi, 1996, p. 264, compare Ermolenko, 1998, p. 96], personifying a Raven.

|

Kül-Tegin portret from Kül-Tegin monument

courtesy of

www. kusadasi. net/info |

26

The name Kyzyl Karga was also imprinted in the Türkic toponymy. After arrival in Kucha (now SUAR Chinese People's Republic), M. M. Berezovsky's 1905 expedition went to the Kyzyl-karga district where it found ancient manuscripts [Litvinsky, 1988, p. 32, note].

In the Usun myth, Uechjies killed Nandou-mi, a father of Sun-god Hunmo. Hunmo was born after the death of his father, and was left in the steppe. This plot became widely known after Sima Qian composed his “Historical notes”. It was used by the scholars of that time as a historical parallel to prove the divine essence of the Chjoustan ancestor Houtszi, reportedly born without a father, by a divine intervention. Using for that purpose a “Sünnufilian" version of Sima Qian, a philosopher Van Chun (27-97) wrote (in E. M. Yanshina translation): “The van (leader) of the grandsons of raven (Usuns) was named Kunmo. Sünnu attacked and killed his father, his mother gave birth to Kunmo. He was abandoned in the steppe, ravens brought him meat in their beaks to feed him. The head of the tribe was amazed by that and decided that he is divine, took him and brought him up. . . Houtszi should not have been abandoned, therefore the horses did not trample him, and birds covered him with their wings. Kunmo should not die, therefore ravens brought him meat and fed him" [Yanshina, 1984, p. 81-82].

The role of she-wolf is clear, she is a deity of fertility and

earth-water, a Dragon embodied as she-wolf. In the Türkic genealogical myth the same functions

bore she-Dragon - she-wolf. It is

important that the Raven - Sun feeds him with meat which is a flesh

of the totem. In other words, Hunmo is a terrestrial embodiment

of the Sun god. This is also

reflected in his name. The hieroglyphs

Ñ11918, 8428 (昆莫) khun-mo (< γuən-mak/guan-mak),

with the standard transmission of the transcriptional final -n of

the foreign sounds, and also -r, -l, with -n, ascend

to a appellation *hvar-baγ/*hvar-bag and corresponds

to the Iranian hvar-baγ/hvar-bag “Sun-god”. The contemporaries knew and remembered the divine essence

of Khunmo. In addition to the conclusion of the tutor, who construed

that the baby was a god, the head of the Sünnu, as stated the “Historical notes”, also regarded him to be a god [Sima Qian,

ch. 123, p. 1140, f. 9b]. Once, a Sünnu cavalry was sent

to a war against Usuns. But the troops refused to fight and “left"

because the Usun army was headed by the

god (Shen) Hunmo [Ban Gu,

ch. 61, p. 750, f. 4à].

27

It is believed that the western area of Usuns was a

valley of the river Ili. In the west Usuns bordered the Kangar state

(Ch. Kantszüy/Kangju) in

the valley of the Syr-Darya river. This proposition does not consider substantial

circumstances. The source tells that between Usun and Kangju countries was a

state Ushan-mu, in conjugal relations with Sünnu leaders: “between Usun and

Kangju was a small state Ushan-mu" [Ban Gu, ch. 94à, p. 1127, f. 37b, Bichurin, 1, p. 85].

North from Usun was a state Ile which Chjichji-shanyu intended to attack [Ban Gu,

ch. 70, p. 85, f. 82].

It existed at least until the 4-5th centuries (see section Yantsai

below). In the Chinese

annals this was the name for the river Ili [Malyavkin, 1989, index].

But in the descriptions of the Usun country the river Ili is not

mentioned. Northwest (should be “northeast"?) of Usun was a state

Üeban/Yueban (Urpen, Orpen)

[Li Yanshou, ch. 97, p. 1292, f. 14b-15à, Bichurin,

2, p. 258-259]. In the beginning of the 8th century still remained a toponymic trace of that state

in the name of the district Orpen or Orpün. Probably,

the eastern part of that country was the district Urbün (Tuva).

There happened a battle of Eastern Türks with the troops of

the Chik people,

who lived in the territory of modern Tuva. The question of

localization of the western Usuns' state remains

unresolved until present. Specialists on the sources concordantly correlate it to

the Dzungaria territory

[Kryukov, 1988, p. 235, with historiography of the problem].

28

The story is designating precisely the location of the Usuns/Asmans, living “together with Great Uechji" “between Tsilyan (Qilian) mountains and Dunhuan”. Tsilyan (Qilian) mountains is a Richtgofen ridge in Nanshan mountains.

Probably in the Ban Gu version the words of “Historical notes”, read “and the former lands of (prince) Hunie are vacant" instead of the “former Hunmo lands are vacant”, can be embraced as sufficiently proven [Sima Qian, ch. 123, p. 1141, f. 10à]. The subjects are the Uechji lands seized and annexed to Sünnu, and the Uechji princes Hunie and Sütu in service of Sünnu. In a battle with Han armies (121 BC) they lost some tens of thousands killed, and Shanyu recalled both of them to his court to execute them. The princes did not return to the court, and instead of executions chose to become Han subjects. But in the last moment, Sütu changed his mind, and Hunie killed him. Hunie with his tribe went to the Han’s territory, where he was given 10 thousand households “for feeding" [Ban Gu, ch. 17, p. 146, f. 4b]. The Hunie tribe in the middle of the 2nd century BC coached in the middle part of the Gansu province, where the Hans later created districts Chjanie and Tszütsüan. The name of the tribe and the name of the prince Ñ4324, 3588 hun-e (< γuən-na/guan-na < *hvarna, hvarana) corresponds to the name of the haurana Scythians, and to the Haurana city in beyond-Imeon Scythia of the Ptolemy “Geography" (VI, 15, 3-4). Hvarana of the Chinese source is an Iranian symbol of royal fortune hvarənah/hvaranah, emanation of the Sun - hvar [Dushesne-Guillemin, 1962, p. 203-204]. With a large dose of probability can be assumed that the Hunie (Hvarana) tribe was a tribe of the priest-keeper of the royal farn (karma? luck? - Translator's Note). Precisely there, to the Uechji's central lands, the Usun (Asman) Hvar-bag (Hunmo) was asked to return.

Prince Sütu and his tribe coached east from the tribe Hunie (Hvarana), in

the area of ancient and modern district Uwei/Wuwei

in the Gansu province [Shiratori, 1930], the transcription Ñ8851,

2643 sü-tu (< khiəu-da < *xuda) ascends to the Iranian

term khuda “god”. The description of that tragical

episode, when Han’s armies under command of Ho Tsüybin in

the 121 BC killed and took prisoner some tens of thousand of Sünnu (Uechji

flying the Sünnu flag!), says that at that time was seized

(cast from gold or plated with gold) portrait of a gold

man (tszin jen), in front of which the prince Sütu (Khuda), “made

sacrifice to the Sky" [Ban Gu, ch. 94à, p. 1118, f. 20à-b, Bichurin, 1, p. 65].

29

Is known the history of his son, he received a surname Tszin - “Gold”, and name Jidi, he went from being a stableboy to a closest man to the emperor. The sculptural group of the royal clan U also had his portrait [Chavannes, 1893, p. 26-27]. Probably, the Hunie (Khvarana, Khvar-bag) and Sütu (Khuda) tribes represented the solar fraction of the state. The following message is not clear if it refers to the same, or absolutely different “Golden man”. In 31 BC Han's court through its viceroy granted (returned?) to Usuns the Golden man [Ban Gu, ch. 96b, p. 1169, f. 7b, Küner, 1961, p. 91]. A similar image was found in the area of the Issyk city of the Alma-Ati province, and by now it has gained a world fame. Its ideological importance is shown in the monograph of A. K. Akishev, who characterized it as “cosmocrator and demi-urg, a warrior embodied as antropomorphic Cosmos" [Akishev, 1984, p. 82]. In 250 years (approximately in 177) this tribe is mentioned by Ptolemy (VI, 15, 3) next to Khaurans Scythians under a name of Khut Scythians.

Written sources do not allow to definitely discern the family and

community form in the Asman

(Usun) society, though the fact of Asman (Usun) departure from a gynocratic

state is an indication of the change, it could not be a result of

one-time migration. In this sense the figure of Butszü-sihou who in

the

genealogic myth takes the newborn, worries about his food, and

comes back to Sünnu (in this case they undoubtedly are Uechji in the Sünnu

confederation) is indicative. No one stops him.

That means that he was a “trustee father" (Ch. fu-fu), with a right to take a

newborn. Only a blood brother of the mother, the uncle on the maternal side, like a mother in a male

embodiment, has such right during a transition from maternal-rights family to patriarchal family. In

ethnography this phenomenon is called avunkulate (from Lat. Avunculos “uncle”).

30

Along with theoretical understanding of this phenomenon [Levi-Stros, 1985, p. 41-47, Outlook (Ru. Mirovozrenie), 1989, p. 40-46], there are studies of the factual ethnographic material [Kosven, 1948]. At that stage the man does not move any more into the house of his wife, just the opposite, he takes her in his house ("in marriage”). The matrilocal spousal residence is replaced with patrilocal one. But at the same time the wife and her children retain their affiliation with the former maternal family and clan. At that time the maternal family is already headed by a man, a father or a brother of the woman given into another's family or clan. In such system the uncle on the maternal side is regarded as the real father of the child, instead of the blood father. And although a mother remains in the husband's house, her children (sons) “return home”. The blood father and his relatives are obligated to turn the child over to his uncle, “return" him to his family. M. O. Kosven called this order “return of the children”.

The first literary message about avunkulate belongs to Tacitus

(Germania, VIII, 18-20). F. Engels on this occasion wrote: “Crucial

importance has one place in Tacitus where it is said that the

brother of mother looks at nephew as at a son, the some people

even think that blood bonds between uncle from the and nephew

are more sacred and close than connection between father and son, so when

hostages are demanded, a son of a sister serves a better

guarantee than the own son of the man who warrants a guarantee. Here

we have a vestige of the clan organized by a maternal right, hence

the initial stage" [Engels, 1975, p. 152]. The nephews were

all-powerful and used exclusive privileges in the family of the

uncle on the maternal side. Relicts of this custom are also known at

present. According to the Kazakh common law, nephews could take anything

from relatives of mother up to three times [Argynbaev, 1975, p. 35]. In the Kyrgyz

past, the nephew on mother side at a feast at an uncle or grandfather could take any horse from their herd, take any

delicacy. Even

survived a proverb “Better come seven wolves than one nephew (from

the mother line)” [Pokrovskaya, 1961, p. 52-53].

31

Butszü-sihou “returned home" the newborn “god - sun" Hunmo”. The word Ñ5651, 8697 sihou (<*khiəp-g’u) is a title. The second hieroglyph Ñ8697 hou (<g’u) of this transcription in ancient Chinese language meant a title of second hereditary noble of the five upper classes. F. Hirth has successfully compared the transcription sihou (<*khiəp-g’u) with a title yavugo on the Uechji -Kushan coins from Kabulistan and yabγu of the ancient Türkic monuments [Hirth, 1899, p. 48-50]. This title is first of all an Uechji title, or, in the opinion of the eminent scientist, it is a “true Tocharian” title. In the 11 BC an Uechji from the Sünnu state fell in the Han captivity, he was a “chancellor" (Ch. syan) with the title sihou (yabgu). After 4 years he returned to the Sünnu shanyu. Shanyu gave him his former post of a “second (after Shanyu) man in the state" and retained the title sihou (yabgu). The bearer of this high title did not belong to the Sünnu dynastic line, described in detail in the sources and is well-known. Probably, he was a member of the numerous Uechji autonomous diasporas in the Sünnu confederation. This history suggests that in the Usun (Asman) state Butszü-sihou was a yabgu.

The word Ñ6492, 12983 butszju (<*pwo-dz'iog) can correspond to a title bhozaka (Bhojaka) on Hephtalite coins of Zabulistan. Bhojaka, or Great Bhojaka is one of the names of the great solar god at Saks of India, meaning “savior”, "deliverer" [Ghirchman, 1948, p. 44-46].

The assumption about the existence of the

Uechji

autonomous diasporas in the (Usun) Asman state is based on facts. First,

it is a direct statement of the chronicler that in the state “live the tribes

(chjun) Se (sak) and Great Uechji “[Ban Gu, ch. . 96b, p.

1166, f. 1b].

32

In the (Usun) Asman state were Uechji sacral symbols and Kuyan areas (Ch. Tszüyian, “Milky Way”)and Akas/Akasa (Ch. Eshi, a residence of queen of the Moon). The mass migrations of the nomadic tribes carried with them the names of theiir gods, and the former names of the holy areas turned up in the new lands. The areas Ñ4297, 11347 Tszüyian (Kuyan) and Ñ14521, 6579 Eshi (Akasa) also turned up in the Usun (Asman) country. They are written by different hieroglyphs than the standard designation of the Edzinagol names, demonstrating by that a different location, but the episode in which these names show up are again connected with the queen. Mindful of a frontal attack by the Han armies, in 73 BC shanyu sent an envoy to the Usun ruler, with a demand to surrender to him a Han princess given in marriage to the ruler, so that her presence at the capital would protect them from danger, and thus deprive the hostile Usuns of the help from the Han. The princess refused categorically, and asked the emperor to take military measures. In response, Sünnu captured the Usun provinces Tszüyian and Eshi [Ban Gu, ch. 96b, p. 68, f. 4à, ch. 94à, p. 1125, f. 33b]. Where the Uechji chancellor Bojaka-yabgu (Ch. Butszju-sihou) was returning to, with a newborn god on his hands, becomes clearer now.

Probably, the lines that Hunmo had more than ten sons was a

continuation of the theme about throne succession and type of family. The

allusion to the “ten sons" of the ruler is a statement

about the military-administrative structure of the state based on a

decimal system. The description continues: “The middle

son, Great Lu, was strong (by character). He was a good military leader,

he headed an army of 10 thousand (and more) horsemen and lived separately.

A senior brother

of Great Lu was a successor to the throne, and the successor to the

throne had a son Tsentszou. The successor to the throne (before

death) told Hunmo: “Declare Tsentszou (after me) a

successor to the throne! “Hunmo agreed out of a pity (to the dying).

Great Lu was angry. He called his senior and younger

brothers, rallied people to a mutiny, and intended to attack Tsentszou. Then Hunmo

gave Tsentszou 10 thousand (and more) horsemen and ordered him to

live separately. Hunmo also had 10 thousand (and more)

horsemen for his own protection. The state was divided into

three parts. The general authority belonged to Hunmo" [Ban Gu,

ch.

96b, p. 1167, f. 2à, compare Küner, 1961, p. 76].

33

Tri- partite division is typical

for the nomadic states. It is

based on a military principle of attacking with left and right wings

or flanks, led by the center, and similar formation during multi-group

encircling hunts. In each wing, members of the tribes belonging to

it were stationed in exact hierarchical order, depending on the place occupied

by them in

the traditional structure. The Sünnu left (eastern) wing had a

privileged status, there was a successor to the throne, there

was the residence of the queen. In the 7th century, such was

the ten-arrow Western Türkic

Kaganate, which was located “on the lands of

the former Usun (Asman) state" or “on the former Usun lands”. The backbone of the Kaganate consisted of ten Türkic tribes, five in each

wing. The first in the list of tribes of left (eastern) wing is

listed a

tribe Ulug-ok/uk, which was a conjugal tribe of the Kagans from the western branch,

from the “celestial-blue" Ashina tribe.

The social-official term ulug (Ch. Hulu <

γuo-luk < uluγ “great”, "senior”)is found in the Ashide tribe

(< *ashtaq, see section 2) in the Second Türkic Kaganate. It was a

tribe of the co-ruler chancellor and katun queen, the spouse

of the Kagan from the Ashina tribe. Only Ashina offspring on the

father side and Ashtak offspring on mother side could inherit the

Kagan throne. Succession to the throne followed the established so-called “brotherly family" along the line “senior brother - younger brother -

nephew (a son of the senior brother)”, with compulsory participation of the queen's

Ashtaks at each step of the sequence.

34

The Queen and chancellor held a decisive vote in the election of the Kagan, performed in accordance with the norms of the “brotherly family”. The Ashtaks represented the lands and people of the state. The bearers of the title Ulug had a position of “chancellor”, "vizier”, "state elder" in the later times also. For example, in the archaic text of the “Turkmen’s Family Tree" (17th century), the “ruler of the state" (il ulugy) was a mythical Dib Bakui, a son of Amuldja-khan [Kononov, 1958, p. 39, line 151]. The son of the elder (ulug) and aksakal ("white-bearded" - Translator's Note)of Uigurs, Erkil-hodja, was a vizier of Kün-khan ("Sun - khan”): “Kün-khan appointed him a vizier and followed his advice until his death" [Kononov, p. 49, line 473-474].

The above source allows to uncover elements of the twofold scheme in the Usun (Asman) state. Pointing directly to tri-partite makeup presumes a presence of a left (eastern and prestigious) wing, a center (ruling base) and right (western, generally younkers and military) wing. Both annals noted left (eastern) and right (western) military leaders, and other similar rank positions [Tszyan Botszan, et al. Lidai. . . , 1 , p. 408, 414, Küner, 1961, p. 73]. The second man after a Supreme ruler is called a chancellor (Ch. syan) Great Lu. Ancient Chinese sound of hieroglyph Ñ9509 Lu (< luk ~*luk) can be viewed as an incomplete transcription of the already familiar Türkic term uluγ “great”, "senior”. Examples of such incomplete transcription of this particular word are found in other Chinese texts [Hamilton, 1955, p. 85, 158-159]. Thus, the preceding word Da “Great" (in a combination Da lu “Great Lu”)is a calque translation of the Türkic ulug.

The Western Türkic Ulug was a head of a tribe Ulug-ok/uk, a

martial partner of the Kagan “celestial-blue" Ashina tribe. The

tribe Ulug-ok was a first among the five tribes of the left wing in

the Western Türkic Kaganate. The Usunian Great Lu (Great Ulug) is

named as a middle of ten “sons”. Because of the uniformity and

prevalence of the common scheme, identical in its basis, it can be

concluded that Usun Ulug was a member of the five-component left

wing, and his tribe was in conjugal relations with the “heavenly"

tribe of the Usun (Asman) ruler, it was a queen and Türkic-speaking tribe.

35

Detour on base and borrowed lexicon

It should be noted that lexicon of the Chinese and other written sources about neighboring peoples was mainly of military-political, historical, and cultural type, the exceptional mobility and penetrability of which are also well-known today. When an ancient term for differently-lingual people, tribe, or men, is reconstructed according to historical-phonetical developmental trends of the language (in this case Chinese) of a document, for identifying the language of its bearers the term is far from ever being a reliable evidence. Jordan wrote “Everyone knows and pays attention, how much the customs of tribes accept the names: Romans accept Macedonian, Greeks accept Roman, Sarmatians accept German. The Goths mainly borrow Hunnic names. " [Jordan, 1960, p. 77]. Therefore the studies of the Uechji and Usun language, made a century and even half a century ago on the level of science at that time, and without consideration of the related material, can't be taken as fundamental in attribution of these languages, though it would be wrong to reject a rational grain contained in them, if this grain exists.

"Ulug" and “Bori" in Türkic lexicon

Quite a different matter is the base lexicon, to which belongs the Türkic term uluγ, supplied with a Chinese translation and semantically justified as “big”, "great”, "senior”, "elder”.

The same should be stated about the ordinary for the steppe nomadic term

böri “wolf". An

opinion used to exist that it was borrowed from the Iranian languages (Avest.

wahrko,

Sogd. wyrk, etc) and “could not be explained by means of

the Türkic languages" (V. Bang). G. Vambery explains it from

bör, bor “grey"

[Vambery, 1879, p. 202], “that in phonetic, and in the semantic relation

does not cause pointed objections" [Scherbak, 1961, p. 31]. P. Budberg, L. Bazin and V. P. Yudin hold it as Proto-Türkic [Bazin, 1950, p. 248, Yudin, 2001, p. 284-285]

(whether it comes from Nostratic, Türkic,

or Persian, the word “Böri”, and its derivative personal “Boris" were deeply ingrained in the Türkic titulature and personal

names, and penetrated most of the surrounding peoples to a degree

that presently “Boris”, derived from “Böri”, is an

international name with royal repute - Translator's Note).

36

In the Usun (Asman) genealogical myth,

the most important is the image of

a wolf wet nurse. The name Ñ5261, 1434 Fuli (< piu-lyie < böri) is

widely known. First of all, Bori (Ch. Ñ5215, 1434 Fuli < piu-lyie < böri) is a name of a tribal branch in the Uechji queen

realm in the Edzin-gol (Tszüyian) valley, headed in the 119 BC by the governor Bori

(Fuli-van) with the name Chantulo (compare Sanskr.

candra “moon"), who surrendered to the Han, and for

that received a title Hou and a district Syanchen. His former Fuli

district was

apparently transferred to a Han military leader Lu Bode, who

constructed there a fort Chjelu-sai [Sima Qian, ch. 20, p. 342, f. 86,

p. 343, f. 9à, Bichurin, 1, p. 72, 3, p. 23]. Hence, the image

of the dragon-she-wolf wet nurse depicted a lunar Uechji

woman. The same name had one of the Usun Hun-mi [Ban Gu, ch. 96b, p.

1169, f. 7b]. In an ancient Türkic genealogical legend a

she-wolf plays the role of the

wet nurse and pra-mother. Her name is written with

completely identical hieroglyphs Ñ5260, 1434 fuli (< piu-lyie < böri),

and ia accompanied with a translation “lan” “wolf, she-wolf”. In memory

of their descent from the she-wolf, the leib-guardians of the Türkic

Kagan were called fuli/bori, and over his court court flew a

banner with an image of the wolf head [Linghu

Defen, ch. 50, p. 425,

f. 4b]. A leader of an autonomous ulus of the Kaganate had a title

Bori-shad (Ch. Boli-she) [Lü Süy, ch. 1946, p. 1436, f. 1b], and soon

after that the same title had a Türkic viceroy in the subjugated Kai (Si)

state on the banks of the river Shara-muren [Ouyan Sü, ch. 215à, p.

1501, f. 8à]. One more Bori-shad (Boli-she) “guarded" the

dependent Tocharian

state Yantsi (Karashar) [Lü Süy, ch. 1946, p. 1445, f. 3b], and the

father of the Western Türkic Aru-Kagan (Helu) was *Er-Bori-Shad

Yakuy-tegin [Ibid, p. 1446, f. 4b]. The “General Codex"

recorded: “Sometimes (the Türks) establish fulin (< piu-lien < börin),

i. e. kagans. Fulin is a name of a wolf, because of their avarice and

propensity to murder they are given such title" [Du Ü, ch. 197, f. 6à].

37

. . . A son could not inherit his father, therefore Hunmo ostensibly only “out of pity for the dying" successor to the throne agreed to transfer this post to his son, which caused a fury of the Great Ulug, his relatives, and people, who had taken to arms. The arbitrary decision of the supreme ruler to institute a new principle of inheriting the throne by the line “father - son”, bypassing the queen (maternal) Ulug tribe, did not gain support and was rejected at that time.

Soon after describing this episode, the chronicler narrates: “Hunmo was old, and the state was divided. Hunmo could not rule on his own”. Still, Tsentszou became a supreme ruler, but after his death the supremacy inherited not his son Nimi, but his younger brother (?) Venguimi. After Venguimi death, the throne also passes not to the son of Venguimi, but to Nimi, a son of Tsentszou. This sequence shows that the “brotherly family" institute continued, comprising in the succession to the throne the union of paternal and maternal lines.

An important section of the East - West

trade road passed through the Usun (Asman) country, and trying to

entrench in it, the Han court endeavored to coax Usun elite to

orient only on the Middle Kingdom, using military pressure or

collaboration, and generous gifts and payoffs to upper chieftains. An important

tool in that was marrying the Han princesses to Usun rulers. The

structure of intertribal relations started changing profoundly. The

throne, established on the principles of “brotherly family”, was

an embodiment of a concept “land + people + ruler”. But

the influence of the ulug chancellor declined. In the 11 BC a gold

seal with purple cords was taken from the Great Lu, and replaced with

a copper seal with black cords [Ban Gu, ch. 96b, p. 1170, f. 80]. The court undertakes

measures to liquidate the institute of “brotherly family”.

38

In 64 BC, when the mentioned Üanguimi did not receive the Supreme throne from his father, the Han court sent to Usun a dignitary, to express a displeasure. The succession to the throne began go by a descending line “father - son”, and each of the rulers included in their title a word “Hun" (Hvar, “Sun”).

Neighboring the Usuns lands, Ptolemy names “Akasa area"

[Piankov, 1988, p. 194]. The Hans knew it under a name “cruel deity" Ñ14524, 6529 Eshi (< ak-si). This district was

also included in the Usun (!) possessions, and in 74 BC the Sünnu,

demanding surrender of a Chinese princess, captured that district [Ban Gu, ch. 94à, p. 1125, f.

33b,

ch. 96b, p. 1168, f. 4à]. This name is repeated in the name of an

Utigur queen, Akagas, in the report of the Byzantian ambassador to

the Türks Valentine in 576 [Menandr, 1861, p. 418, Chavannes, 1903, p.

240]. The Utigurs of Menandr are Uti, associated with Aorses

of the Pliny “Natural history" (VI, 39). The word Uti was a real proto-type of

a transcription Uechji

< ngiwat-tie < uti [Pulleyblank, 1966, p. 18]. In

parallel, a tribe Uti existed in the east, in the valley of the river Edzinagol

and lake Sihai and Salty (Sogo-nur and

Gashiun-nur respectively). In the 416 a ruler of the state Northern Lian conducted

a military campaign against Uti. Along the route he made sacrifices at Golden mountain Tszinshan and in a temple of

Queen- mother of West Si-van-mu. In the temple was an image of

goddess Si-van-mu, sculpted of a black stone. The ruler ordered to

etch on the stone a dedication text [Fan Siuanlin, ch. 129, p. 853,

f. 6à]. The features of the Uechji goddess-queen are similar

to the image of the Asia Minor goddesses Great Mother Cybele, in a

form of a silver statue with its face sculpted from a rough black stone,

placed in a sacred cart next to a reservoir [Frezer, 1983, p. 330].

Tentatively, it could be asserted that Akasa area was a residence of the Uechji queen.

39

A “common Uechji" symbol was kuyan/gayan (compare Scythian. γaya - “light”, "white”)as a terrestrial embodiment of the Moon and Milky Way. From several hieroglyphic depiction of this word the steadiest is Ñ2109, 11347 tszüiyan < kio-yen. So were called the Uechji main river and lake north from Nanshan (Edzin-gol), as well as the royal clan and the main city of the Western Tocharian (Kocha) princedom Tsütsy (SUAR of the CPR) [Fan Å. , ch. 47, p. 694, f. 4, Huan Venbi, 1983, p. 224-228]. The all-permeating “whiteness" of the short-haired Kuchans was translated into the Chinese language by a word bai “white" [Ouyan Sü, ch. 221à, p. 1552, f. 9à].

One more

Uechji sacral symbol was Tsilyan (Qilian)

mountain 200 li southeast from Chjanie/Ganjou. It was on a southern

border of

the

Uechji proper possessions. “There are fine waters and excellent grasses,

in the mountains is warm in winter, and cool in summer,

(these places) are suitable for pasturing sheep" [Yao Weiyuan, 1958,

p. 200]. The natives of these mountains also were called with surname Ñ14380,

11148 Tsilyan (Qilian) (*giag-lien <*giglen). About one of “Kiglenians" is said that his ancestors were from a

clan of the Noble Woman [Li Boyao, ch. 41, f. 7 a]. In the 5th

century a Hunnu surname Ñ14482, 11148 Helyan (< khək-lien)

was replaced with Tefu ("Mother”)[Wei Show,

ch. 95, p. 1192, f.

18 a-b], though these hieroglyphs could be translated as “iron bridge (cart with dyshl, parents)”. The hieroglyphic

rendition of a sacred mountain, a tribe, a noble lady, etc.

is different, but their old sound is uniform: *kiehlien, *kiəglien,

*gieglien, *khəklien, *khioklien. Their nearest

phonetic and semantic

parallel is Phrygian kiklen “wagon”, "cart”. So

was also called the constellation wagon, the Big Bear. The

semantics of this word

between the forest peoples of Amur is notable. Evenks call the Big Bear

constellation not a Wagon, but “She-moose

Heglen" [Rybakov, 1981, p. 54].

40

The cult of the Phrygian Great Mother of gods, the fertility goddess Cybele was moved from Asia to Rome in April. And the goddess at once took on to work. That year was collected an unprecedented harvest of grain, vegetables, and fruit. On a March 27 holiday “into a wagon drawn by oxen, was put a silver statue of the goddesses with the face sculpted from a rough black stone. The wagon headed by patricians, walking barefoot, slowly adv advanced toward the banks of Almon. There the High Prist, dressed in purple, washed with flowing water the wagon, the statue and other cult objects”.

The ablution of the fertility goddess in the river, by concept of J. J. Frezer, was to recall the rain spells, to ensure enough moisture for budding vegetation [Frezer, 1983, p. 327-332].

Accepting the plausible premise about

Uechji origin of the image of