Kangars in Samarkand

|

||||||||||||||

Links |

||||||||||||||

http://kronk.narod.ru/library/pugachenkova-ga-1987.htm (in Russian) |

||||||||||||||

Forword |

||||||||||||||

Galina Pugachenkova (1915-2007) was an Uzbekistan ancient art scholar, she studied the art of the

peoples who lived in the ancient Uzbekistan territory and adjacent lands. Her many works illuminate

the history of the area from a complimentary angle that gives facts a strong concurring or

dissenting voice in the historical reconstructions. The following 10-page brief

finds Kangar Türks (native name Kang sing., Kangly pl.) not only in the outlining areas outside the cities, but also within one of major

southern Sogdian city, in a prominent capacity. It gives an insight into a physical appearance of

the Kangar local elite, and a priceless insight into the physical distinctions between heterogeneous

phyla of the Kangar elite. It also illuminates a symbiosis between the Sogdian and Türkic

inhabitants that is found to be already well established in the 1st century BC, a continued

tradition rooted in the times much preceding the Ahaemenid conquest, and lasting until present in

spite of all the past religious and political convulsions. The art allows to discern otherwise murky

subjects, and gives mute burial remains a voice, providing a veracious essence for popularly phrased "The devil is in the details". I want to note a self-respect and scientific freedom asserted by G. Pugachenkova in her brazen invoking of the native names for the implements found or depicted in the art. That linguistic honesty is another tribute to her scientific candor and objectivity, especially contrasting against the unflattering background of compliant docility. The translation skips on minute descriptions of details that would not be of interest for a general reader. Unedited portions of machine translation of these details are given in a smaller font, and will show in the print even if the browser is instructed to ignore font settings of the original posting. Extraneous notes and comments are shown in blue. Page numbers are shown in blue at the beginning of the page. Additional illustrations for the descriptions narrated in the text are highlighted with blue headings |

||||||||||||||

|

G.A.Pugachenkova Image of the Kangars (Ch. Kangju) in Sogdian art |

||||||||||||||

|

Problem of mutual relations of the population of settled agricultural oases and nomadic steppe - one

of radical in a history of Central Asia, yes in essence and all Middle East. In special displays

they are opened in art culture which products have or environments of feature specific to created

them, or marked by mixture of them, or the maximum scene of reunion, organic synthesis

show. And in its originality and an originality of art of the Central Asian region at different

scenes of its historical development are especially brightly embodied. In the least measure this synthesis appears in architecture which progress is entirely connected to a city civilization, in the greatest - in products of applied arts. Fortress Kurgan-tepe in Orlat village in Koshrabad district of Samarkand province became an object of excavations by Uzbekistan art expedition in 1980. These are the remains of a large city in the ancient Sogd, located in a valley of descending from low mountains and gorges river Saganak . Its monumental citadel, its fortifications enclosing residential parts of city, the remains of substantial inner buildings, they all testify to an advanced and long-term city life. But manifestly, in the upland behind the river is spread a huge kurgan burial field, in a micro-relief numbering hundreds of washed off kurgan burials, and counting the washed off kurgans and kurgans destroyed by tilling, doubtless there were many more. And the archeological artifacts from excavations evidence their synchronism with the settling of the city. All explored kurgans, in charge of V.A.Karasyov, were plundered in antiquity. But in some kurgans stock were found various artifacts that allowed to date the burials by the 2nd century BC to the beginning of our era: iron weapons (apparently, they were thrown out because by the time of plunder their iron has rusted, was deformed, and did not have a value), clay vessels, some ornament pieces unnoticed in the darkness, when the robbers scooped the funeral artifacts (for example, pieces of gold threads and foil, bronze buckles), or left as not wanted. One complex of such ornament is worth discussing. They are taken from a kurgan where were preserved many objects: iron weapons - a long sword, which handle crosspiece was decorated with a magnificent bright green greenstone, fragments of a dagger, two sheaths, three-petal arrowheads of different size, pieces of bone from a composite bow. Were found fragments a thick gold thread which, apparently, once trimmed a precious fabric. Was also found a large single-handle jug with small triangle nozzle on the opposite side from the handle. (Is it an intended blindness of the archeologists, or an arrogant illiteracy that mentions the jar of the drink given to the deceased warrior, but skips on the food that the drink was accessory to? This is a Tengrian must - provide the deceased with necessities of travel to another world - Translator's Note) But of a special interest were the shoulder blades, apparently fastened to leather: two large, and four small. In one of the adjacent kurgans were also found eight small rectangular plates. Almost all bear drawings distinguished by high artistic skill, very interesting in content, iconography and style. Large plates are rounded on the one side and vertically trimmed off on the right and on the left. At the corners and along an axis are fastening holes, on the side of an axis is an oblong gap, on the other axel is a wide rectangular groove. The plates were fastened with thin nails, across a groove they were fastened with a thong. The plates are obviously paired, their form and fastening grooves mirror each other. The inside of the plates is smoothly shaved and clearly show the layers of bone structure.

The external surface is polished and engraved, apparently with a needle-type tool.

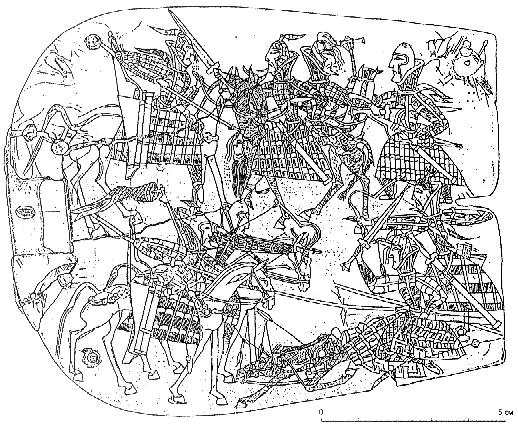

Battle. Depicted a vigorous battle scene of four pairs of mounted and foot knights, those at the left are defeating contestants on the right. The fighters are composed in four spatial plans from bottom up: 1. A mounted knight, apparently, a main character, because behind him is fluttering raised bunchuk attached to the horse . With a long, bent spear he stabs a kneeling contestant. He is still swings a sword, but the staff of his spear is already broken, and his horse fell, pierced by an arrow. 2. A knight on a galloping horse pulls a bowstring, the same is also doing an opponent standing opposite him. 3. A horseman at the left has pierced with a spear the horse of an opponent, who has a decapitated bleeding head of one of earlier killed enemies attached to his harness, and he in turn slams with a sword, covered with drooping blood, the head of his opponent. 4. The horseman on the right stubbed with a sword his dismounted opponent, but perishes himself because the opponent broke his skull with a "tabar-zagnul" battle club, slushing his blood. All participants are of the same ethnic type and wear identical military armor that differs only in details. Their faces are depicted in profile. A head of one of the soldiers is bared (a helmet, apparently, was lost in the battle), his skull is narrowing toward the top, the other soldiers wear helmets. All battle participants wear armor of a long caftan type that snuggly fits the breast, with dense arm plates, extending from top to bottom, covering knees. The neck and a nape are protected with the high reserved collar intercepted for reliability by a thong with brushes fluttering behind. Legs of soldiers are not protected - they in the fitting trousers tense bands under sole. An armor of soldiers lamellar and scaly, made from sown on a basis square, oblong, semi-oval plates and from the intermediate belt connections given to an armor flexibility, and at each participant the variation of these details. Hunting. Its participants are placed in three parallel lines with an illusion of three spatial plans, though perspective reductions are not present. Action occurs pa a background of the mountains designated in two plans by conditional peaks, on them - the trees also very conditionally treated in the form semi-oval on a core, the branches subdivided by arches to vertical shading between them; in one case fanning lines designate a bush.

The horsemen

race on the horses stretched in a flying gallop, their legs are extended horizontally forward and back.

The horsemen ride in the saddles very close to the horse withers, with strongly tensioned bows that just

sent arrows into pursued animals. The horsemen legs are pulled back and strongly bent in knees,

they compress the sides of the horse, their toes are extended like ballerina's toes. This leg position

is distinct from those of the mounted fighters in battle.

The ethnic type of all three hunters is the same, as of the soldiers: a similar profile, claw-like beard, hanging moustaches. The heads of two men are uncovered, and the middle horseman, apparently a main person in that scene, wears on the head an oval kulyah (Türk. kulakh/kulyakh - a traditional male felt hood among the people of Near East and Middle Asia - Translator's Note) cap. They are dressed lightly, in accordance with their task, which needed non-constraining clothing. On the right, to the saddle is attached identical long threefold quiver, as carry the soldiers. The type of horses and their harness are almost identical to that are represented in a battle scene, but is n distinctions. At the bottom and top horses behind a magnificent bang above cut comb the mane leaves the high pointed comb. The harness of horses is a little bit facilitated - ahead the saddle is attached by only simple belt girth. At middle n top horses at the left the magnificent brushes fluttering during gallop. The top and bottom hunter go on mares, middle - on a stallion. This horse is covered with a body cloth, at others it is not designated, a tail magnificent, with wavy locks of hair. At distant marethe tail (on a plate it is seen in part) also is free, but locks are located differently; it in the beginning is densely drawn, in the middle is picked up wide buckle, further flutters locks. Horsemen pursue racing animals (their images unfortunately are very corrupted). The bottom horseman pursues roe deer - male, female, and a fawn; the middle horseman pursues three koulans (their long muzzles resemble the muzzles of racing behind them horses, all have long wavy tails), the top horseman pursues two corkscrew argalis. They all are representatives of Central Asian mountain and steppe fauna. Small plates have the form of as though squeezed petal, with a wide strip above. On a strip three round apertures for fastening by bronze pins (on one plate of them it was kept two, on another - one, other are lost) n larger, also a round aperture above the mentioned bottom point. On three plates images are engraved: Duel of two knights in the same armor and with the similar weapon, as in a battle scene; left has already pierced right, and that has only touched his spear. On the right to a side of one - the quiver with bow and, apparently, with arrows, left to a side of another on two thongs is suspended a long sword in narrow sheath; Fight of two two-humped camels; both on half-bent legs, both bite each other rear leg; The left half of image was erased. Right - a vulture pecking a prey (not clear).

These plates were obviously

fixed as an ornament which drawings could be considered close. But an ornament of that and where?..

They could make out an armor-clad armor, serve as a detail horse gear, and the big plates,

probably, used in facings of a quiver. This question is still open.

Appearance of scene participants. The characters on the large and small plates have the same anthropological type. The skulls of two hunters with uncovered heads, and of the warrior who lost his helmet, are dome-like narrowed, low upright forehead, hair is combed up, at temples the hair is brushed behind ears, and trimmed above the neck in a circle. All participants have small, rhomboid eyes, fairly large nose with a small hump, hanging almost to the chin moustaches thinning to a point, vigorous chin, the majority wears a pointed claw-like beard. No Mongoloid attributes are present. We have not found their direct analogues. The hairstyle is somewhat reminiscent of the Gerais from the Khalchayan sculptures [1] and the hunters on the plates from Tahti-Sangin [2], but the profile and the form of the beard of Kurgan-Tepe characters is different. Closer to them are the portrait profiles on the Sogdian coins of the 2nd century BC - first centuries AD, which the numismatists connect with the Samarkand Sogd [3]. The coins bear a few basic groups of so-called "barbaric imitations" which E.V.Zeimal breaks down as follows: early Sogdian imitations of Antioch mint (obverse - a head of a sovereign to the right, reverse - protoma (front part - Translator's Note) of a horse to the right); early Sogdian coins (obverse - a head of sovereign to the left, reverse - standing archer); the coins of Girkod group attributed to the 1st-2nd centuries AD (obverse - a head of a sovereign to the right, reverse - protoma of a horse or archer). The profiles on the obverse of these coins are not identical; sometimes the face of a sovereign is stout, beardless, but more often (and in Girkod group always) is thin, with an elongated beard; possibly emphasizing an age difference. At the same time, with these feature differences, it is completely clear that these coins carry not the portraits, but a particular type, and not so much of a concrete ruler as a "conceptual" sovereign or a revered ancestor, a founder of a reigning house.

The personalities on the Kurgan-Tepe plates display typological similarity with the a bearded

profile found on the Girkod and earlier coins - dome-shaped skull narrowed at the top, hairstyle, form of moustaches, large nose. But appreciable differences

are also visible: Girkods have a squeezed sloped forehead, reminding Gerai's characteristic forehead

deformation on the coins and deformation of Geraid Khalchai sculptures [4], straight nose, a

drooping narrow beard. And the Kurgan-Tepe soldiers and hunters have a straight forehead, aquiline

nose, a hook-like beard pointing up. These differences are not accidental,

the carver demonstrated anthropological type features of the personalities.

They are one people with the Girkod clan, in those days they lived in the Samarkand Sogd, but they were another tribe, apparently a tribe that controlled possessions in the Miankal region. Anthropological materials from Sogd for the period of interest for us are not numerous. Nevertheless, from the available skulls is clear that, for example, in the Bukhara Sogd, the agricultural population, and those groups that buried their deceased in the kurgans, belong to the eastern Mediterranian type. The cattle breeding population of the Sogd foothill and mountain areas was also Caucasoid [5]. The warriors and hunters on the plates give a visible image of the appearance of Miankal population in the Samarkand Sogd zone. They had a distinct profile with no Mongolic traits. Attire of hunters: fitting the top half of torso the caftan, zapahnutyj from left to right up to a waist where draw a belt{zone}, then extends, covering hips, and ponizu is decorated with a wide strip of a fringe; trousers densely cover legs and are fixed under a foot shtripkami above fitting dense, as a stocking, footwear. Breed is identical, but the carver has tried to depiction a variety in details of a suit variations of fine shadings, and at the bottom horseman a caftan in general without shading (except for sleeves). The costume is similar, but only generally, with the attires of a number of Asian peoples in the last centuries BC and in the beginning of our era, known from the art monuments. For example, attires of early Kushanian Gerai clan members typically have a soft shirt or a dense caftan, lapped over from right to left, and magnificent wide draping trousers [6]. The members of the Great Kushan clan (Kushan coins, Gandhara and Mathura sculptures) has either a caftan tightly buttoned in the middle, or a shirt without a slit, and the wide trousers with many horizontal folds [7].

About arms of a plate give extremely substantial material. Not pressing in detailed analysis, we

shall note, that an armor-clad armor at all participants - uniform type, but development of

elements is extremely various. Most schematically, only with allocation of the basic components, the

armor in a scene of a duel is depicted. Breed of it is like a caftan which fits the

top half of torso, and from a waist strongly extends, is lower than knees and is covered with a set

of rectangular plates. The high high collar covers a neck and a nape where it will delay a

little and is expanded: sleeves are free at shoulders, are narrowed to brushes. On legs same, as at

hunters, dense trousers with bands and fitting soft footwear. The top part of an armor is divided into breasts by a vertical strip and to two cross, at vertical riflenii formed{educated} by them is direct Squares, but at one of participants - entirely a scaly covering. The bottom half gives six variations of lamellar registration (at two participants she{it} is not visible). The small scale of the images does not allow a conclusion about armor-clad plates and scales fastening method, but the variety of large and small parts allows to conclude that one assembly combined various metal, and probably leather plates and scales with a quilted or felt substrate. Helmets had a semi-oval form, rising at temples before transitioning to cheek plates; on the top was a tip with a ring for affixing a kuiruk tail (Türk. kuiruk = little tail - Translator's Note). The surface is smooth, or covered with vertical or horizontal plates, or scaly. The helmets of this type belong to the category of so-called "Kuban" oval helmets, already from the middle of the 1st millennium BC spread in a huge Scythian area from Scythia to the Middle Asia. Kurgan-Tepe helmets have no direct analogies. In their outlines and form of the cheek plates they best resemble the helmets on Khalchayan sculptures (at the turn of our era) [8] and a royal helmet of Huvishka on his coins (2nd century AD) [9], however Huvishka military headdress has a more elaborate structure. The armor-clad armor depicted on the Kurgan-Tepe plates has a number of parallels in the Kushan world, from Bactria to Gandhara [10], with no direct matches. Like in the attire of the hunters, we note general commonality but absence of exact congruity. The commonality was dictated by identical system of fighting and defense, and the difference was caused by ethno-tribal differences which were thoroughly followed in those days. The arms of the soldiers are spears with lance-like tips; very long two-sided swords with elongated handle expanded in cross-section at a joint with the sword blade, and artfully widened at the end; straight long sheaths suspended from the belt on two thongs; composite bow; arrows with three-faceted tips; a long three-section quiver with a wide compartment for the bow and two narrow compartments for arrows, attached on the right to a horse saddle; oblong shield vcovered with plates of various forms; one of the warriors has a battle ax, known in eastern arms terminology as "tabar-zagnul" (Türk. "crow beak axe"). Such tabar-zagnul is shown on the reverse of Soter Megas-Kadfiz I coins (1st century AD) where it is held by a ruler sitting on a horse or his sanctified ancestor [11]. The armored soldiers ride light horses which are not protected by the armor, and with exaggerated long bodies and exaggerated long muzzles. Their manes are trimmed with a comb, between ears is left a hair bang. The tails apparently are strapped, they are very narrow, the locks are depicted only for two third of the length. The horse harness contains double bridles on the muzzle, fastened with cheek-pieces, and one bridle under a neck, small kuiruk tails of the same type that crown the helmets of the horsemen are attached to the horse ears; connected by the big and small rings, the girth embraces a neck and is attached to a low saddle (visible only on the fallen horse) from which extend large rings holding tail cinch. Stirrups are absent. The horsemen ride close to horse withers, compressing its sides with straight legs, stretching toes almost vertically. Extremely interesting is the standard by the horseman in the foreground at the left. On a high staff is attached a head of large-eared animal (its details are indistinct), behind its neck is a light, fluttering cylinder decorated with diagonal squares, split in two on the end. In her time, K.V.Trever collected materials about such standards, widespread in the Scythian, Parthian, Sarmatian orbit [12] (This list falls short of one more documented tradition, the Türkic standard among European and Eastern Huns, Kangars, Bulgars, Mongolo-Tatars etc. Initially a fluttering dragon effigy represented dragon Baradj, this standard gave root to early European standards influenced by Scythian and Türkic military heraldry, conceptually influencing such standards as French Oriflamme, Danish, Norwegian and Swedish Dannebrog banner, early pre-Mongol Slavic banners, etc. The dragon banner also became synonymous with the Scythian and Türkic invaders, creating a dragon/snake symbol of evil immortalized in the images of knightes killing a dragon, like St.George slaying a dragon. Masguts/Massagets, the neighbors and confederates with Kangars, and who probably spoke a dialect close to the Kangar's, called dragon Baradj "Alp Elbegen". With the advent of Islam, the image of Alp Baradj faded away, together with the rest of Tengrian pantheon - Translator's Note). Their most detailed description is given by Arrian who tells the following: "The Scythian military emblems are the dragons fluttering on poles of proportional length; they are sewed from color rags, and the head and whole body to the tail is made like a snake, to present a most terrible appearance... When horses rest in place, (you) see only multi-colored cloth, hanging down, but in motion they are inflated by wind so that they become very similar to the named animals and at speed (they) even whistle from strong gust passing (through them). These emblems not only by their appearance cause pleasure or horror, but also are useful to signal an attack, and for different groups not to attack one another" [13].

All these details are present on the Kurgan-Tepe plate: the head of the dragon, its trunk made of

rags (apparently, multi-colored in life), blown up from the motion of the horseman, a pair of fluttering

tails. K.V.Trever, describing a banner of a similar standard from

Ostyako-Vogulsk

(deep in Siberia, in Khany-Mansi lands by the confluence of Ob and Irtysh, the former lands of

Kipchaks and Kimak Kaganate, depending on the dating of the find - Translator's Note),

speculated that it

was made in Iran, getting with time to Siberia; "we do not have any reasons to assert its

Central Asian origin" [14]. Now, we have a concrete proof of the

Central Asian origin. Description of the weapons used by the cattle breeding tribes who neighbored the initial location of Sakas, Tochars (Yuedzhi) and Usuns, who in the 2nd century BC flooded Middle Asia, survived in the records of early Chinese chronicles. So, the nomads of Jonyan and Sjanshan had "arms consisting of bows with arrows, lances, sabers, and armors" [15]. As we see, the list completely coincides with the weapons complex of soldiers depicted on Kurgan-Tepe plates. Archeological material from Kurgan-Tepe kurgan burials corresponds with the so-called Sarmatian culture (for Central Asia, it maybe more accurate to call it "Sarmatoid" culture), and the complex of finds allows to date them by the 2nd century BC - 1st century AD, with the kurgan where these plates were found is closer to the earlier date. There are typical long swords with crosspiece handles, a shortish dagger, composite bow, three-faceted petaled arrowheads, single-handle jug with small beak - all this is inherent to the complex of Sarmatian weapons and goods [16]. It needs to be also emphasized that the contents of our kurgans in many respects find analogies in the Bukhara and Sogdian Samarkand burials the 2nd - 1st centuries BC (Kuyumazar, Lyavandak, Adjar, Mirzakul burials) - of the same type are the swords, daggers, arrows, jug, an one-sided mustahara flask [17]. Emphatically, the arms depicted on the plates, supplemented with spears, fully approach those of the Sarmatian type. In recently published M.V.Gorelikom detailed research kushanskih an armor references to my article about parfjanskom and baktrijskom armor-clad arms [18] which ostensibly contains the statement, as if sako-Tochars (Yuedzhi) tribes are given, being nomads, could not as such have own heavy protective arms being the privilege of settled peoples [19]. It does not match the validity for in the article it is specified, that though in environment of the ancient Central Asian peoples mentioned under collective names of Scythians, Massagets, Sakas, the main kind of military contingents were legkovooruzhennye archeri-cavalrymen, among nomadic znati the heavy protective arms [20] was applied also. Other business, that formations katafraktariev, that is tjazhelovooruzhyonnyh kopejshchikov and mechebortsev, in a combination to infantry, is typical with III-II centuries BC and later in system of the large states of Middle East. We adhere to this point of view and until now. Kushansky the armor, M.V.Gorelik's which studying founds{establishes} mainly on monuments of the fine arts of Bactria and Gandhary, testifies, that in system Greko-Baktrijskogo, Sako-Parfjanskogo, the states Kushanskogo the armor receives an exclusive variety of types and variations. Only during this epoch there are and actually katafraktarii, that is reserved horsemen on the reserved horses. The tribal distinctions noted on the plates are noteworthy not only in the type of haircut, attire, amour, but also in the horse equipment. The horse gear complex in the hunting and battle scenes does not find direct analogies in the extensive cycle of hunting and battles found on the paintings, reliefs and especially toreutics of the Middle East. They are also absent in the tying of tails of the noble racers, an excellent variety of which for example gives the Sassanian art [21]. On Kurgan-Tepe plates the horsemen in armor and helmets ride horses not yet protected by any armor. At the same time, along with similarity of armor and helmet forms, exist an exceptional variety of the armor, where the types of plates, scales, fastenings all vary. Is that indicative of the rank of the soldiers? Likely no, because the difference in ranks is usually indicated by special regalia that we do not see. But the scope of this variety testifies to thye production of the armor details in weapons workshops with advanced traditions and professional skills. Such workshops apparently were located in the large Sogdian city Kurgan-Tepe, where were fulfilled orders for those who then were founding rest in the located near that city kurgan burials. Equally can be reasonably suggested that the production of the bone plates took place in the artisan workshops of the large Kurgan-Tepe city: the skill of the artists who engraved on the bone the complex and full of expression compositional scenes is really high. And the artists who produced them took into account wishes of the customers, depicting on the drawings not only their ethnic type, clothing, and arms, but also close to them scenes and events. Who were those customers and who is depicted on one of the small and on two large plates? History will tell us.

In the 1st century BC Strabo wrote about the Central Asian tribes: "From these nomads received fame

in particular those who took away Bactriana from the Greeks, Asii, Passians,

Tochars and Sakarauls, which came from the area on the other bank of Iaksart (Syr-Darya) next to

area of Sakas and Sogdians, occupied by Sakas" (Geography, 11, 8.2). In that citation the important for us

fact is the process of movement, in a period preceding Strabo, of the nomadic contingents, when the

Sogdian areas were occupied by the Saka tribes, were called in a generalized form the tribes of the

Middle Asian Scythians. The second half of the 2nd century BC was marked by fierce movement of peoples who lived in the extensive open spaces in the north and northeast from Syr-Darya, the impulse to which was given by a pressure of nomadic Hunnu (Huns) people. Among these peoples were Sakas, who reached Bactria, but then were displaced by Tochars (Yuedzhi). The areas of Horesm, Shash (Chach) and Sogd captured Kangars, and then on the Jeti-su lands settled Usuns. Initially all of them were nomadic or seminomadic peoples engaged in cattle breeding and only partialy in agriculture. The Tochars (Yuedzhi) and Kangars in the zones of ancient agricultural civilizations assimilated in the local population, gradually changing the character of their economy, and joining the city culture. At the same time the lifestyle, ideology, customs, etc. of the newcomers were strongly connected with the age-old ethno-tribal traditions. In particular, this applies to the traditions of kurgan burials and corresponding funeral ceremony, which are distinct most essentially from the Zoroaster funeral cults of Bactria and Sogd. One of the reports of a Chinese minister stated: "Nomadic peoples can be subdued, but to change them is difficult" [22]. The ancient Chinese chronicles narrating the events of that time, call confederations of nomad tribes which filled the cultured oases of Central Asia south of Syr-Darya Yueju (Tochars) and Kangju (Kangar), and note that Kangars "in traditions are totally like Tochars (Yueju)" [23]. The Tochars (Yueju), who captured Northern Bactria, which after a defeat of the Greco-Bactrian empire by the Sakas fragmented into a number of small possessions, organized there five tribal Djabgu princedoms, from which by the beginning of our era came ahead a tribe of Kushans, who united all other princedoms, and soon after that created the extensive Kushan empire. A similar process initially was happening in the Kangar (Kangju) possessions. The chronicle mentions "five small Kangar (Kangju) possessions", citing their names that coincide with the names of the main cities - Suse, Fumu, Yuni, Gi, Yuegan [24]. This phonetic transcription greatly distorts the Central Asian names, but from the above five names of Kangar (Kangju) provinces at least three received their localization, helped by the records of later chronicles. Fumu is the Miankal region, Yuni is Shash/Chach - Tashkent, Gi is Bukhara?, and Yuegan (Urgench?) is Horesm. Later chronicle states: "He, or Kuishaunniga and Guishuanni is the ancient city of Fumo, which belongs to a small Kangar (Kangju) possessor" [25]. The Kushania, mentioned by the Arab and Persian authors, was located in the region of interest for us, and in the Middle Ages was a blossoming city, second in rank after the city Ishtihan. Having settled in the Central Asian lands, Kangar (Kangyui) took a position of an independent state confederation, reported with irritation by a Chinese viceroy: "Kangar (Kangyui) is proud, arrogant, and does not agree to bend before our envoys. The officials sent to it from the viceroy, they place below the Usun Princes" [26]. Apparently, Kangars better preferred the friendly contacts with their direct neighbor, Usuns. The clan of Kangar (Kangju) possessors of Sogdian Samarkand (Kan) in the first centuries AD became so powerful and respectable, that after all the cataclysms in the middle of the 1st millennia AD he retained his significance in the early Middle Ages. To him run the genealogy the representatives of different branches of that clan, who down to the capture of these lands by the Türks owned the areas of Bukhara. Kashka Darya, Zeravshan, and Syr-Darya oases in the 6th-7th centuries [27] (It is interesting to note that Frye completely misses the Kangar period in the Middle Asia, totally conflicting with the archeological observations of G.A.Pugachenkova. In Frye's scenario, all landlords remained Ahaemenid dekhans (feudals), Persian in culture and language, and foreign to the ruled population. Frye does not stop to discuss kurgan burials, or artistic depiction of Kangars, or Kangars' possessions in Bukhara. Kashka Darya, Zeravshan, and Syr-Darya oases. In Frye's scheme, the Persian landlords, former soldiers or satraps of Ahaemenids, remained in place until Arabs kicked them out and replaced them with an Islamic system of global equality. But Frye does note that the Persian landlords remained a foreign element in the Middle Asian lands. For an attentive reader also would be interesting the story of irrigation canals, the aryks, which in the Middle Asia are attributed to Kangars, and long before the onslaught of Ahaemenid irrigation-crafty soldiers. As a side note, the best Ahaemenid soldiers were cavalry, which consisted of Scythian/Sakas/Tocharian/Kangar nomads who gained landlord rewards, and were again thrown to control the meek agricultural subjects, likely speaking their language - Translator's Note) At the same time, in contrast with the Tocharian (Yuedzhi)coalition of powerful, centralized Kushan empire, the Kangar (Kangju) confederation covering the areas of Horesm, Shash/Chach, Sogd, and some other lands, remained friable, and its unity nominal. To it is quite applicable the characteristics of the chronicle of the 1st century BC - 2nd century AD: "Each possession in the "Western Territory" has its sovereign. Their armies because of division are weak and are not joined under single rule" [28]. The large city of the possession Fumu was, apparently, Kurgan-Tepe. It can be reasonably suggested that the plates from Kurgan-Tepe burial are depicting members of the Fumu branch of Kangar (Kangyui), which owned the Miankal zone. Notably, the battle scene depicts not a battle of two conflicting peoples, but an internecine fight, bacause on both sides the participants are fellow tribesmen: they have uniform ethnic type, military attire, weapons, horse harnesses. Apparently, it depicts an episode of initial intra-tribal conflict and struggle for the power, that brought a victory to one of clans. This event, with historical roots, could get a character of a legend and become a local epos.

The hunting scene also can be correlated to the legends about brave knights, masters

of mounted

hunting art, which

the inhabitants of the Central Asia were famous for, especially its nomads. The chronicle of that epoch especially emphasizes that the inhabitants of Fergana (Davan) "are skilful in shooting from a horse" [29]. The role of valorous troops and a horse among Kangars, who seized Sogd, was such that on the reverse of the above Sogdian coins in the first centuries before and after beginning of our era, is depicted an image of either a standing archer, or a galloping horse. As to the small plates, one of them depicts a duel of similar in appearance and ethnic affiliation opponents; another depicts a furious nomadic entertainment, a camel battle, and the third depicts a gryphon ripping off a prey, a variation of "ripping scene", popular in Saka (and generally in Scythian) art, where however usually appears not a vulture, but a noble eagle (For significance of Kyzyl Karga - Red Raven, its association with the act of Creation, its embodiment of a noble Eagle, and its significance in Indo-Türkic sacral imagery, see Yu.Zuev - Ancient Türks). Drawings on bone plates that contain so many most interesting realities, not in a smaller measure deserve attention as for now unique (though, undoubtedly, not unique for their time) works of fine arts of the ancient Sogd. The fine arts works of the ancient Sogd till now were known in ceroplastics (terracotta of Sogd, Varahshi, and other fortresses) and few fragments of late antique sculptures and painting (Er-Kurgan). are Connected in their contents with the Sako-Kangar (Kangju) traditions, the Kurgan-Tepe plates appear as a phenomenon of small forms early antique arts, which, probably, also had correspondences in monumental forms. These drawings testify to a mature artistic direction. The stylistic distinction of the images is in the dynamics of action - boisterous battle fight or a duel, violent gallop of hunters and a flight-like run of rushing animals, complicated turns of the horses in the top group of fighters on the large plate, and camels on a small plate. With a smooth background, with the absence of perspective, amazing is the skill to depict the space with a multi-plane arrangement of figures (battle, camels), or vertical distribution of planes (hunting). Should be noted a fidelity to the nature in the depiction of people and animal images, and at the same time the conditionality of the methods that strengthen the total intensity of action (animals flying in gallop and their exaggeratedly elongated proportions). At the same time, an absence of a landscape or a minimum of its graphical depiction is typical, the hunting scene hints on the nature, in the battle scene the nature is totally absent. Though some motives are introduced by a Kangar (Kangju) flow, connected with the habitual for Central Asian nomads principles of Scytho-Sarmatian animal style, on the new soil they passed through a filter of high professional art of the masters of ancient Sogd. With the Scythians is connected a tradition of deliberate enlengthening of drawings and horse muzzles, and especially tradition of pursued animals in a hunting scene, which amplify the dynamics and rampage of their gallop and race. At the same time, comparing with the Scytho-Sarmatian art, on the images on plates we note different traits. Working on the order and desire of the Kangar (Kangju) tribal nobility, which owned that area, and, apparently, constituted a ruling elite in the city, the bone carvers brought to engravings nobility and clarity of lines, and an art of composition, testifying about their high professional school and artistic skills transmitted from a generation to a generation. At the same time in there reigns a realism inherent to the ancient art. If in the Scythian art dominates stylization, which at times is almost turning an image into an ornament, here prevails the reality of events and realism of the images . In the Scythian "animal style", with its conditionality and stylization, which determine its startling force, lays a magic meaning. Probably, in some measure it is preserved on the Kurgan-Tepe plates with images of animals, however, the measure of stylization is not great. But in both scenes, the events and actions have a real sense for their customers, and accordingly real images. Here we note a phenomenon like that was in Northern Pontic, where in the 4th-3rd centuries BC artizans from the Greek cities produced art objects on orders of local population (battle scenes on quiver and a comb from Soloha kurgan, images of Scythian warriors on precious vessels from Kul-oba and Chertomlyk kurgans). In a similar manner in the large Sogdian city Kurgan-Tepe, where Kangars settled in the 2nd century BC, highly professional bone engravers produced for them the described set of bone plates with engraved images. These images relay not only the appearance of Kangars, but also the spirit of Kangar (Kangju) life, embodied by the skills of Sogdian artists.

The tradition of engraving drawings on bone will also survive in Sogd in the Early

Middle Age period. Such is a fragment of a bone comb from Aitugdy-tepe (Kashkadarya Sogd), where is

shown a

shooting archer riding a galloping horse, he wears a fitting caftan, similar with caftans on Kurgan-Tepe

archers in a

hunting scene [30]. Meanwhile both scenes, battle and hunting, by their composition and style in many respects

heralding a development of these "crown" scene

in the Sogd painting of the 6th-8th centuries, and in all Middle Eastern toreutics of the pre-Islam times. |

||||||||||||||

Notes |

||||||||||||||

|

[1] Pugachenkova G.A. Sculpture of Halchayan. Moscow, 1971, ill. 63-67, 73-79, etc. |

||||||||||||||