Ma Yong and Wang Binghua

History of civilizations of Central Asia Volume II

The dawn of civilization: earliest times to 700 B.C.

The development of sedentary and nomadic civilizations: 700 B.C. to A.D. 250

Editor: Jams Harmatta Co-editors: B. N. Puri and G. F. Etemadi

UNESCO Publishing

The following are excerpts, quite extensive as minimally required for educational purposes, about archeological finds in present mainland China, and some conjectures about their provenance. UNESCO publications generally deserve highest confidence, because they are mostly stripped from nationalistic biases, except where these biases are acceptable to all participants. Since UNESCO, and UNESCO publications, exist on donations from every inhabitant of the Earth, the use of the published materials by the same inhabitants should not be too controversial.

The citation is closely following publication, with some minor

modifications in paginations of partial phrases and pictures,

adopted for Internet use, and addition of tribal names in addition

to conditional names. Chinese scientists directly name the most

likely people, known from the historical records of the time,

instead of faceless conditional culture monikers predominant in

the Russian archeological publications. In those cases where likely

correspondences between reconstructed ancient Chinese phonetics and

accepted modern names are established, the Chinese name is dubbed

with modern name, in bold; posting clarifications are in

italics blue:

Yüeh-chih - Uz-tribes (Ch. Yuezhi, Yüeh-chih, dial. Juz-tribes,

Tokhar and As confederation )

Hsiung-nu - Huns (Ch. Hsiung-nu, Xiung-nu)

Wu-sun - Usun (Ch. Wu-sun, "Raven Clans", Kaz.

Uisyn/Uysyn)

The culture of the Xinjiang region*

The Xinjiang region

The Xinjiang region of China lies in eastern Central Asia to the north and south of the T'ien Shan mountain range. South of the T'ien Shan mountains lies the Tarim basin, bounded on the west by the Pamir plateau, ''the roof of the world'', and on the south by the Kunlun and Altyn Taq mountain ranges. These three sides consist of high mountain peaks permanently covered with snow and ice, with few passes by which they may be crossed. The east side of the Tarim basin, however, is comparatively low and gives access to the Gansu corridor. The basin is rather like an inverted trapezium, with its centre occupied by the wide Taklamakan Desert. The melting snows of the Kunlun, T'ien Shan and Pamir mountain ranges flow from different directions towards the desert, forming short inland streams. These give rise to a number of oases, but each is relatively small; and the desert that separates them makes communications difficult. From antiquity it has been impossible for people to live anywhere but in these oases on its borders. North of the T'ien Shan mountains lies the Dzungarian basin, shaped like an isosceles triangle, with the Altai mountains to the north-east, and a few low mountain ranges to the north-west, but no major barrier to the east or west. South of the basin in the T'ien Shan range there are many valleys with flourishing vegetation, The lands near the Urungu and Irtish rivers, with the upper reaches of the Hi, are all suitable for nomadic grazing. The principal evidence for the history of Xinjiang in the centuries before the Christian era comes from archaeology. There are few reports in Chinese written records and these seem to be largely derived from hearsay. It has been suggested that the tribes living in the remotest east, mentioned by Herodotus (IV. 13) quoting the poet Aristeas, were the ancient peoples of the Altai mountains, but this is mere conjecture.1

|

* See Map 6. 209 1. Sun, 1984. |

209

The Xiangbaobao graves, Tashkurgan

The grasslands in the valley of the River Tashkurgan (Stone Kurgan, 38°N 75°E - Translator's Note), some 4,000 m above sea-level, but still suitable for nomad grazing, have a large number of ancient graves still visible on the surface covered with blocks of stone. Forty graves of this type excavated at Xiangbaobao yielded Carbon-14 dates between the seventh and fourth centuries BC 2 In spite of varied methods of burial - sometimes inhumations in various positions with a wooden cover over the grave pit and sometimes cremations with no wooden cover - their funerary contents are basically uniform and belong to a single cultural type. Four graves contain the remains of human sacrificial victims. Most bones are decayed, but one well-preserved skull is of a Europoid type. The tombs contain few funerary objects, suggesting a poor, unostentatious life-style. Finds are mostly everyday utensils with hand-made pottery made from clay containing coarse sand and mica flakes, fired at a low temperature. Most of it is undecorated, with an uneven red-brown or grey-brown surface color. Cooking implements and containers - cauldrons, jars, dishes, bowls and cups - predominate. This pottery has distinct marks of use, even to the extent of repair after breakage, and is found with metal objects such as iron knives and bronze arrows. The ornaments found include gold plaques, bronze or iron rings, earrings, buttons and terracotta, stone, bone and agate beads. A few bronze ornaments shaped as a pair of sheep's horns (Fig. 1) represent quite a high level of craftsmanship. Besides, these the graves have also yielded cloth woven from sheep's wool, sheepskin clothes, bones of animals (mostly sheep) and birds, and a wood-drill fire kindler of the type commonplace at oases in the Tarim basin. It is clear that these localities once supported fixed settlements of inhabitants who raised livestock, particularly sheep, as their principal economic support.

Hunting was an important supplementary occupation; the level of craftsmanship was quite low, but the use of metal was developed. Distinctions between rich and poor had already appeared in this society. It is not clear whether the variation in styles of burial was due to racial differences or chronological factors, but the coexistence of inhumation and cremation suggests that there may have been an amalgam of cultures. This locality borders Saka territory to the west and adjoins districts where the Ch'iang (Tibet) people lived to the south. The Europoid skull from an intact burial may represent the Sakas. The prevalence of cremation among the Ch'iang tribes may be seen in written records of the pre-Chin period.3 These graves of the Tashkurgan region may therefore represent a mixed culture of the Saka and Ch'iang (Tibet) tribes.4

|

2. Chen, 1981. 3. Mo-tzu, Chapter 6; Chieh-tsang b; Hsun-tzu, Chapter 19; Ta-lueh Lu-shih ch'un-ch'iu, Chapter 17; Hsias-lising-lau, 1. 4. Russian archaeologists have excavated ancient graves, similar to this culture, in the Pamir region in the former Soviet Union. See Bernshtam, 1952. These scholars believe that they belong to the Saka culture. |

210

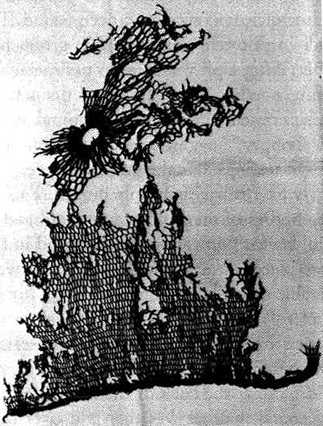

Fig. 1. Bronze ornaments: one is shaped like a pair of sheep's horns.

Xiangbaobao, Tashkurgan.

The Lou-Ian graves at Lop Nor

In antiquity Lop Nor was a large salt lake at the hub of communications between the Gansu corridor and the Tarim basin, but changes in the course of rivers have caused it to dry up and become a salt marsh. The famous Lou-Ian site lies on the north-west bank of the Lop Nor marsh, where the Kongque river now flows into the marsh. In the first century B.C. it was the capital of the state of Shan-shan. The graves found near by used to be considered as graves of the Western Han period, but recent Chinese excavations have yielded material from the seventh to the first century BC.5 These graves have a coffin chamber of wooden planks in a shallow pit. The corpse, laid in an extended position, was wrapped in a woolen cloth, and wore hide boots and a peaked brown felt hat with bird feathers.

| 5. In the past there were many reports of this culture type in the Lop Nor region. See Stein, 1974; Huang, 1948. In recent years the Archaeological Research Institute of the Xinjiang Academy of Social Sciences has made three surveys near the Lop Nor, and on the lower reaches of the Kongque river, and has gathered a collection of fairly complete scientific materials. They are currently being collated and a report will soon be published. |

211

The borders of the women's hats were often embroidered. The woolen cloth was gathered into a pouch on the upper chest and filled with fragments of branches of the medicinal herb ephedra. They also contained a small basket woven from hemp or grass containing up to fifty grains of wheat.

Due to the extreme aridity, many of the corpses have been preserved. Their physical features are very clear. They have golden hair slightly curled, a high nose, deep-set eyes, rather long eyebrows and narrow cheeks. Anthropological measurements suggest Homo Alpinus features, similar to the ancient peoples of the Pamirs and Hindu Kush regions. The graves also contain wooden and stone female figurines, with long, round faces. They have clothes woven from wool and wear a pointed hat, with long hair falling in plaits over their shoulders. Their physique presents an interesting study, depicting the physique and dress of the people of the time. Most of the funerary objects found are articles of everyday use and include ornaments. In early tombs there is no pottery, and utensils are made of woven grass, wood, bone or horn. They used wild hemp and tamarisk branches to make cups, jars and baskets, utilizing varying textures to create patterns. Occasionally the exterior of a basket is daubed red.

Wooden basins, cups and spoons, as well as horn cups, are quite common in finds. Felt was used widely for clothes and everyone had a felt hat. Woollen clothes are almost all of plain pattern and are generally coarse, of relatively good quality. The hides have been tanned, craftsmanship is quite high, and there are many varieties of attractive leather boots. Beads, strung together and hung around ankles and neck - some of amber, agate or jade, but mostly made from the bones of small animals or birds - were used as ornaments. Groups of bone tubes about 10 cm long were sometimes linked together and worn round the waist. Among the funerary objects there were also large numbers of sheep and ox bones.

It is easily seen that raising of domestic animals, fishing and hunting were the principal economic activities of the inhabitants. Their life-style depended primarily on their animals but they also made use of local wild plants. A small quantity of wheat grain was found among the funerary objects but no agricultural tools have been found and there are no traces of agricultural fields or irrigation works of the period in the vicinity. This clearly suggests that they did not follow an agricultural economy and probably received the grains of wheat in exchange from neighboring tribes who were engaged in agriculture.

The Lou-Ian sites lie within the ancient territory of Shan-shan, where the soil is both sandy and saline. In describing the state of Shan-shan, the Han-sku says that the earth is sandy and salty and its fields are few. It has to rely for grain on neighboring states. Grain was a particularly precious commodity and its scarcity, because there was no local production, accounts for the low living standard of the area. The ornamentation employed, however, points to quite a developed aesthetic taste in an inhospitable climate.

212

The pebble graves of Alagou (Turfan County) 6

At Alagou, below the southern slopes of the T'ien Shan mountains near the Ordos grasslands, many ancient graves have been found. There are two principal types, suggesting two different cultures. One group has a very distinctive pebbled burial chamber. After a pit was dug, its perimeter walls were lined with pebbles to form a tomb chamber 2 m deep with a diameter of 2 to 3 m. Tombs of this type with similar contents have also been found at Lake Ayding-kol and Subashi in Shan-shan County,7 suggesting an extension of this culture into the Turfan basin. Carbon-14 testing date the graves between the eighth and second centuries BC. The early graves have multiple burials. Each grave contained between ten and twenty bodies of men and women, old and young, piled on top of each other. They all lay face upwards with the head in a westward direction. Funerary objects were placed near the head and at the waist. Below the waist was placed a considerable quantity of bones of sheep, horses, oxen and camels, apparently intended to reflect the deceased's material prosperity. In some instances, hair arrangements were preserved in a recognizable style. They had all worn their hair long, parted centrally, with each half combed into plaits and kept in place at the back of the head by a bone or wooden hairpin. A delicately woven silk hairnet was then put over the top (Fig. 2). Many short wooden combs were found in the graves which had presumably been used for combing out the plaits. There were a great variety of woven materials, much rather coarse and loosely woven, but some heavy woolen cloth was of a high standard. Some cloths were plain woven, others interwoven. Light blue, light red and deep black dyes were employed, and striped, criss-cross and triangular patterns were used. All this is clear evidence of a developed weaving industry of a high standard ( Fig. 3). In fact several wooden and clay spinning whorls, used for twisting woolen thread, were found. The inhabitants clearly practiced animal husbandry, but there is also evidence of agriculture. Some pottery jars were found to contain crop seeds such as flax. There is also evidence of hunting in the wooden arrow-shafts and three-edged arrow-heads filed from hard wood. There were some bronze objects, but most implements for everyday use were made of wood and pottery, often painted with a light black pattern on a grey-red body - vessels such as jars, dishes, bowls, jugs and cups all being made by hand. They are decorated with triangular, net, whorl and pine-needle patterns (Figs. 4 and 5).

|

6. The excavation work of the Alagou pebble-grave sites was

directed by Wang Binghua of the Archaeological Research Institute of

the Xinjiang Academy of Social Sciences, and altogether eighty of

these graves were excavated. For a brief survey see Archaeological

Research Institute, 1979. 7. The excavation of the ancient graves of Lake Ayding-kol and Subashi was undertaken by the Cultural Observation Unit of Turfan, Xinjiang. The materials have been kept in this unit and are currently being arranged. |

213

Fig. 2. Silk hairnet. Alagou, Turfan County. |

Fig. 3. Woollens. Alagou, Turfan County. |

214

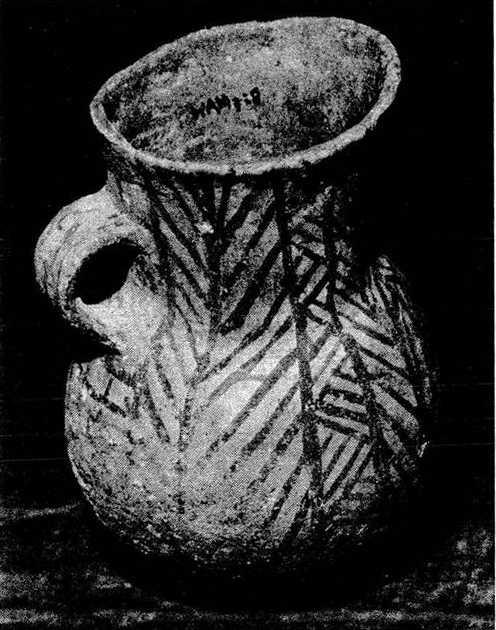

Fig. 4. Painted ceramic jar. Alagou, Turfan County. |

Fig. 5. Painted ceramic jar. Alagou, Turfan County. |

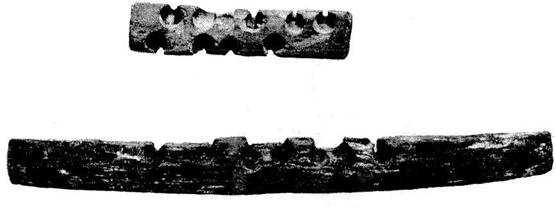

Wooden objects including trays, bowls, spoons, cups and plates with engraved designs (Fig. 6) point to the skill of the artisans. There are a considerable number of bronze objects, primarily round bronze plates and small bronze knives; and wooden fire drills are found in virtually every grave. It must have been the normal method for obtaining fire at the time (Fig. 7).

In craftsmanship the ornaments have great individuality. There are many strings of beads of bone, agate and jade, and both bronze and gold earrings. There are also ornaments made of cowrie shell. Some bone ornaments are carved with heads of animals such as wild boars or bears, in a vigorous style. Graves of the later period are rather different. The practice of multiple burials was replaced by single or double burials, suggesting a change in social structure. Graves are still pebble-lined, but now contain a wooden bench supported by four pillars. Funerary objects now include iron tools and weapons and craft products such as silks (Fig. 8), phoenix-pattern embroidery and lacquer cups, imports from China.

215

Fig. 6. Carved wooden plate. Alagou, Turfan County. |

Fig. 7. Wood-drill &e stlck |

| 216-217 | |

The proportion of plain pottery (mainly of a red-brown and grey-brown color) greatly increased. Some new vessel forms are introduced, particularly the high-footed pottery cup and wooden dish. All these changes show that the inhabitants were increasingly subject to the influence of the culture and economy of China. The early graves of the Chü-shih (巨师?) people from the north of Yaerhu in Turfan County have funerary objects, other contents, and pottery basically similar to those of the Alagou pebble-grave culture,8 and this suggests that the pebble-graves at Alagou also belong to' the Chü-shih.

The wooden chamber graves at Alagou (Turfan County) (same as Pazyryk Arjan-type kurgan - Translator's Note)

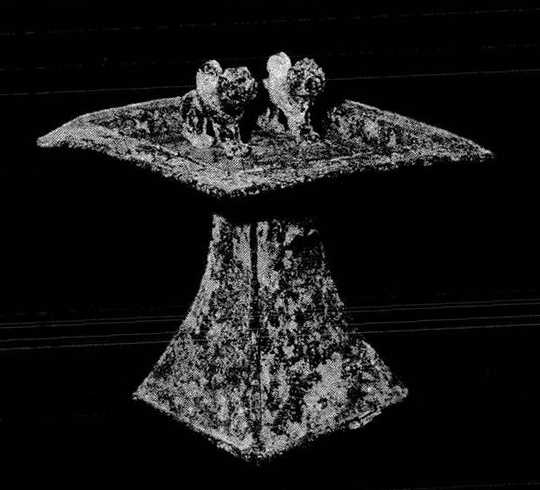

Not far from the pebble-grave sites at Alagou, ancient graves belonging to a different cultural type have been found.9 These graves appear as kurgan heaps of stones at ground level. Beneath there is quite a large vertical pit with a volume of some 200 m3. The pit is filled with sand and piled stones which seem to have been brought from the nearby river bed. In the centre is a wooden coffin-chamber constructed of pine, which abounds in T'ien Shan. The wood, cut to size, is arranged in a criss-cross manner, vertically and horizontally, to line the four walls of the pit, and the roof is also covered with wood to form a coffin-chamber. The dead were buried singly or in pairs, always lying flat with the face upwards. It appears that some sort of red pigment was applied before burial. In most graves the chamber had caved in due to the collapse of stones above, when the wooden roof decayed. The skeletons are generally poorly preserved, but enough survive to suggest that they had a well-built physique. Carbon-14 dating places these graves between the fourth and second centuries B.C. The funerary objects found are rich in quantity and equally refined in quality. Many are gold luxury items such as beads. There are also round gold plaques, rather thick and heavy, beaten into a tiger pattern by a hard molding tool. The tiger's body curves in a semi-circle in an active and expressive pose. These plaques, originally fixed in leather, seem to have been used to decorate belts. There are more than 100 gold-foil flakes, no thicker than a sheet of paper. Some are in the form of animals, others are shaped as willow leaves, or formed into diamonds or circles. The animals on these gold-foil flakes may be leaping lions or a pair of tigers crouching face to face. There are holes at the edges and at the two ends to enable them to be sewn as ornamentation onto clothes. Serving the same purpose were similar plaques in silver, also pressed into a range of animal designs (Fig. 9). There was also a remarkable bronze tray consisting of three separate parts - a square stand, the main body and two lion-like animals standing in the centre of the tray. The three sections had been cast separately, and then welded together by pouring liquid bronze on to the joints (Fig. 10), This unusual type of bronze tray with animal figures has also been found in ancient graves in the Hi valley in Xinyuan County. There were also a few iron knives and arrows intended for domestic use. The standard of smelting of the gold, copper and iron objects is good and the metal, except for objects in silver, is relatively pure.

|

8. Huang, 1933. 9. Wang Bingliua, 1981, pp. 18-22. 218 |

218

Fig. 9. Silver plaque from a wooden chamber |

Fig. 10. Bronze tray with two statues of lion-like

animals |

219

Fig. 11. Lacquer tray in situ in a wooden chamber grave. Alagou, Turfan County. |

|

Other luxury goods are agate beads, pearls, silk goods (such as a diamond-pattern gauze), lacquerware, trays (Fig. 11) and cups which came from the Yellow River region and provide evidence for trade links with China. Everyday household utensils include articles in a fine smooth pottery burnished to a glossy surface. The pottery objects are generally hand-made of fine craftsmanship, and have been fired at quite a high temperature. They include bowls, dishes, trays and small cups. Some vessels have three flat feet affixed to the base of the bowl - an unusual feature. These objects are very different from the pottery vessels recovered from the pebble-graves in the same locality.

Most of the funerary objects from the wooden chamber graves are household utensils and superior luxury goods, rarely production tools. It is clear that the persons buried in these graves must have been the chief nobles, not ordinary members of the nomad tribes.

The north-south orientation of these graves, the wooden coffin-chambers and their contents suggest an intimate connection with the Usun (Ch. Wu-sun, "Raven Clans") culture in the Hi river basin. 10 Similar graves, also aligned from north to south, have been found between Zhangye and Tun-huang in the Gansu corridor. The Han-shu says that the Usun (Ch. Wu-sun, "Raven Clans") tribe originally lived in the western part of the Gansu corridor together with the Uz-tribes (Ch. Yüeh-chih, dial. Juz-tribes ), but escaped to the Huns (Ch. Hsiung-nu, Xiung-nu) when the Uz-tribes (Ch. Yüeh-chih, dial. Juz-tribes) killed their chief.

| 10. The Archaeological Research Institute of the Xinjiang Academy of Social Sciences has undertaken many excavations of the Hi river valley Usun (Ch. Wu-sun, "Raven Clans") graves of the Han period, the successive directors of this work being Yi Manbo, Wang Mingzhe and Wang Binghua. Parts of the materials have already been published. See Archaeological Team, 1962; Ma and Wang, 1978, pp. 14-15; Archaeological Research Institute, 1979. The majority of materials has not yet been published and is stored in the Archaeological Research Institute of the Xinjiang Academy of Social Sciences. |

220

A generation later, the Uz-tribes (Ch. Yüeh-chih, dial. Juz-tribes) were defeated by the Huns (Ch. Hsiung-nu, Xiung-nu) and forced to migrate west to the Hi valley. To avenge this ancient wrong, the Usun (Ch. Wu-sun, "Raven Clans") attacked the Uz-tribes (Ch. Yüeh-chih, dial. Juz-tribes), drove them out and occupied their land. These events took place in the first half of the second century B.C. (Han-shu 61, Biography of Chang Ch'ien; Han-shu 96, Record on the Western Regions.)

It may be recorded that the years in which the Usun (Ch. Wu-sun, "Raven Clans") tribes depended on the Huns (Ch. Hsiung-nu, Xiung-nu), after they had been driven out of their homeland in the western part of the Gansu corridor by the Uz-tribes (Ch. Yüeh-chih, dial. Juz-tribes), represented a period of greatness for the Huns (Ch. Hsiung-nu, Xiung-nu), with their power and influence possibly extending over the Altai mountains to the west. This was the time when the Alagou District of Turfan was under the control of the Huns (Ch. Hsiung-nu, Xiung-nu); and it can therefore be suggested that the Usun (Ch. Wu-sun, "Raven Clans") tribes perhaps lived here under their protection, and the wooden chamber graves might be attributed to the Usun (Ch. Wu-sun, "Raven Clans"). This context is consistent with the Carbon-14 dating, the geographical situation and the period of time covered by the wooden chamber-grave culture at Alagou.

The T'ien Shan settlements

Below the northern slopes of the T'ien-Shan mountains, where grass grows in profusion, grazing is excellent and land suitable for cultivation. Many sites that were associated with settled cultures have been discovered. In the east, scattered through Tuergan, are a series of sites usually between 1,000 and 2,000 m2, while the largest is 7,000 m2.11 The remains of houses with thick walls of earthen bricks (Engl. adobe, Tr. saman - Translator's Note) and stone built to resist the severe winters of the region are still visible. The most interesting objects found are the large number of stone-mill trays. At Kuisu thirty to forty were found, several being worn from long use. At a number of sites painted pottery, stone axes, stone adzes, heavy bronze axes and bronze knives have been found. These sites lie between Lake Tuer-kol in the east and Lake Bar-kol (the famous Pu-li Sea of antiquity) to the west. The Hou Han-shu says that the state of Pu-li was called after a tribe of that name that engaged in agriculture, while some of its members led a nomadic life. When the Huns (Ch. Hsiung-nu, Xiung-nu) controlled the western region, the King of Pu-li offended the Huns (Ch. Hsiung-nu, Xiung-nu) ruler, the Pu-li tribe were expelled and their land was occupied by a people devoted to animal husbandry who knew nothing of agriculture. It may therefore be suggested that the sites of the ancient settled culture to the east of Lake Bar-kol may belong to the early period of the Pu-li tribe (Tr. Buri, in L.Gumilev's opinion, ancient Bulgars - Translator's Note).

| 11. For relevant material, see li, .959; Wu, .964; and Archaeologlcal Research Institute, 1979 |

221

The ancient village site of Sidaogou, 10 km west of Mulei,12 has traces of habitation in the form of post-holes, kitchen ranges and ash pits. Carbon-14 dating suggests an early occupation of around 1000 B.C. and a later one from around the fourth century B.C. There are few funerary objects from the associated graves, but the habitation site finds included pottery, stone, bone and bronze articles. From the later period new articles have been found such as cups, cauldrons, pallets and container vessels, and the proportion of painted pottery increased, with vermilion coloring making its appearance. Most tools are of stone in good craftsmanship - mill quarries, mortars and pestles, spindle whorls, hoes, adzes, etc. There are bone spindle whorls, needles, combs and arrows, as well as bronze knives, hairpins, rings and ornaments. The bones of horses, oxen, sheep and dogs suggest the involvement of these animals in the economic life of the time.

It is clear that the people living in these areas led a sedentary life and were engaged in agriculture and domestic animal husbandry, with hunting as a supplementary activity. The appearance of terracotta knife moulds suggests that they had already grasped the art of casting bronze objects, while their painted pottery resembles that of the Shajing culture to the west of Gansu.

Grave sites on the slopes of the Altai mountains

The zone between the Altai mountains and the Dzungarian basin provides ideal grazing throughout the year. The nomadic peoples who lived there have left behind them many rock carvings of large-horned sheep, horses and deer, and men with taut bows and flying arrows. But it is difficult to suggest either the time or the people responsible for them.

Three principal types of grave have been found in the zone. The first type is the large stone kurgan found near Huahaizi in Qinghe Province. The largest example of this type of kurgan has a circumference of 230 m, encircled by a ring of stones, with a square polished granite stela 300 m to the north. The stela has carved running deer engraved on two sides. A second stela 10 m to the east has a carved circular and rhomboid pattern, with the carving of a lamb and a short sword. No graves of this group have yet been excavated.13

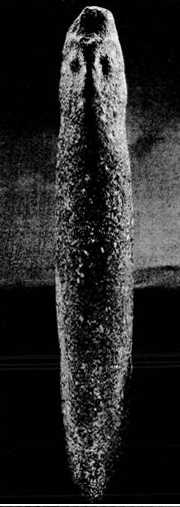

The second type is the ''stone-warrior'' grave, which has an engraved figure of a man standing in front, sometimes represented by a human face carved on the upper part of a large boulder. Some have merely a stone bar symbolizing the human form. Behind the stone warrior there is a square stone coffin made from four enormous slabs of granite, capped by another slab. Inside the coffin the bones were found in complete disorder. There were multiple burials; and the objects found include stone arrows, stone cups, stone jars and pottery vessels with some bronze and iron objects (Figs. 12-14).14

|

12. Yang, 1982. 13. This type of large stone mound was surveyed in 1965 by the archaeological team of the Institute of Nationalities of the Xinjiang branch of the Chinese Academy of Sciences. For materials from the former Soviet Union and Mongolia, see Savinov and Chlenova, 1978. 14. Wang Mingzhe, 1981, pp. 23-32. |

222

Fig, 12. Stone Cup with handle in shape of cow's head from a

stone-warrior grave |

Fig. 13. Coupled stone cups froma stone-warrior grave. Keermuqi, Altai County. |

223

Fig. 14. Small stone figurine from a stone-warrior grave, Keermuqi, Altai County. |

|

224

The third type is the earth-pit vertical shaft grave, a type often discovered in the same region as the stone-warrior graves, but there is no evidence for any relationship between the two.

The three types of grave clearly belong to three different cultures, but the absence of full-scale excavations precludes any detailed discussion of their characteristics and historical backgrounds; also the absence of written records makes it impossible to give any clear answers to questions of ethnic identity. Such a broad study of the different grave-culture peoples of Xinjiang would be incomplete without reference to classical Greek literature, which mentions some of the tribes who might be associated with these areas. Literary works in both China and the West seem to focus primarily on the area to the north of Xinjiang - the slopes of the Altai mountains and the grasslands north of the Dzungarian Desert. This is probably because between the seventh and second centuries B.C. the principal route across Eurasia ran north-west from the Inner Mongolian grasslands near Hetao over the Altai mountains along the Irtish river. Having crossed the south Siberian grasslands, it again went west to reach the land of the Scythians on the northern shores of the Black Sea, as archaeological finds seem to confirm. The evidence from the epic Arimaspea (Tr. Arym-spu, "squinted-eyed", i.e. pronounced Mongoloids - Translator's Note), referring to the Issedones as neighbors of the Massagetae (Strabo XV. 1.6)(Masguts - Translator's Note), speaks for their nomadic identity but it is difficult to identify them with the tribes noted in the Chinese annals. Some Chinese scholars have identified the geographical location of the territory of the Issedones with the Uz-tribes (Ch. Yüeh-chih, dial. Juz-tribes) or Usun (Ch. Wu-sun, "Raven Clans") on the upper reaches of the Hi river and in Xinjiang, but this remains uncertain. What is clear is that between the sixth and fourth centuries BC existed a powerful confederacy of nomadic tribes under the name of Uz-tribes (Ch. Yüeh-chih) living on the steppes to the south of the Altai mountains; and the graves excavated in different areas of Xinjiang confirm the existence of several nomadic groups and throw light on some of their cultural and political relations.

225