Links

|

Genome Biology and Evolution

2013, 5:61-74 http://arxiv.org/ftp/arxiv/papers/1208/1208.1092.pdf http://arxiv.org/abs/1208.1092 eelhaik[at]jhsph.edu |

Supplementary Data files: Supplementary Data - Supplementary_Figures.doc - doc file Supplementary Data - Supplementary_Note_1.doc - doc file Supplementary Data - Supplementary_Note_2.doc - doc file Supplementary Data - Table_S1_-_MT_Haplogroups.xlsx - xlsx file Supplementary Data - Table_S2_-_Y_Haplogroups.xlsx - xlsx file Supplementary Data - Table_S3_-_Populations.xlsx - xlsx file Supplementary Data - Table_S4_-_ASD_non-Jews.xlsx - xlsx file Supplementary Data - Table_S5_-_ASD_Jews.xlsx - xlsx file Supplementary Data - Table_S6_-_ASD_populations.xlsx - xlsx file Supplementary Data - Table_S7_-_ASD_SE.xlsx - xlsx file |

PDF files

| Eran Elhaik Jewish European Ancestry: Contrasting the Rhineland and the Khazarian Hypotheses |

|---|

| 0.6 MB |

|

|

Introduction

Note, that according to E.Elhaik results, of the 14mln Jews (and there are another 6 mln who are all the same genetical Jews but do not go as Jews) for a total of 20 mln, 1/3 are Türkic people, 1/3 Caucasians, and 1/3 Palestinian Jews; or, if we separate the Jewish borsch into component piles, the distilled Caucasians would number 8 mln, Palestinian Jews would number 7 mln, and Turkic people would number 6 mln. That proportion stands in nearly every synagogue on the face of the earth, so when you rub your elbow with a neighbor in a synagogue, you may be rubbing a very Türkic elbow. The fellows that did not migrate westward remained in situ, grew numerically in the same proportion minus very significant assimilation, and by now are spread from Kamchatka to Hawaii. Genetically, they are not connected with Khazars, as demonstrates the following review by A.Klesov, but the “Khazars” is a rather symbolic term anyway.

Also note that the term Ashkenazim was resuscitated during the Middle Ages by rabbis not too literate in history and genetics. The Biblical Ashkenazim referred to nomadic Scythians, and applied as a general term for the Türkic nomadic people. When the Kazar Kagan Joseph wrote that Khazars are the children of Ashkenaz, he was stating a universally known fact that the Türkic people were Ashkenazim, and he wrote that at least 3 centuries before the Middle Ages rabbis. The rabbis knew that too, that's why they initially applied the term Ashkenazim to the migrants from the east, but later they claimed that Ashkenazim came from the west. Many of those rabbis came from the east, and they had well-honed survival skills and the very eastern know-how on how to manipulate and rally masses.

The Türkic people of Eastern Europe, including Scythians and Sarmatians, were slightly Mongoloid, say 10-20% by genes, and by the time they amalgamated into the Khazarian Jews, the proportion of Mongoloidness was diluted by a factor of 3 to 4. Hence, the genetical results among the Ashkenazi Jews record a very minor grouping of Mongoloid genes, on the diagram they are depicted in black.

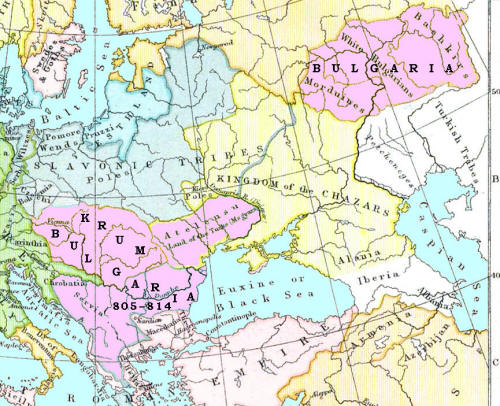

Khazars appeared in the Caucasus together with Bulgars; their previous territory, according to the most credible hypothesis, was the Balkh area, and apparently they were constituents of the As-Tokhar (Ch. Yuezhi) confederation that took over Bactria in the 140 BC. Bactria was immediately adjacent to their ancestral area of the Caspian-Aral mesopotamia and Amudarya-Syrdarya interfluve. S. Klyashtorny speculated that in the 600s Khazars were a rebellious subjects of the Western Türkic Kaganate, and fled to the Caucasus at that time. The term Khazaria is a politonym, and the “Khazars” mentioned in most of the contemporaneous sources have little to do with the ethnicity or genetics. The same applies to the Türkic converts to Judaism. It is most unfortunate that the terms “Khazars” and “Judeo-Khazars”, used in the E.Elhaik's and many other's works, gained a genetic dimension. Genetically, these terms are justified no more than calling “borsch” a “beet”. Beets give borsch a characteristic reddish color, but independent of their confessional affiliation they are very substantially different from the soup called “borsch”. A study on borsch would never be called a study on beets. And a study on borsch using cucumbers as surrogate for the beets has even less chances to be seriously taken as a study on beets.

Lastly, and that is most interesting, Yiddish originated as a Slavic (Sorb) language, and later was re-lexified into OHG (Old High German). Now, with the invention of a heavy plow the Sorbs expanded north-west to the Germanic area from the area of today's Hungary and Bohemia, supplanting the Celtic-Germanic migrants who had only an ard scratch plow. That tells us that first, with Sorbs came their Jewish population that spoke Slavic, and second, that Hungary and Bohemia had sufficient pre-migration Jewish population to create their own Slavic-based language. The Slavic migration started in the 5th-6th cc, coincidental with the arrival of the Avars to the Hungary and Bohemia in 560 AD, and with supplanting of the local farmers to make space for the nomadic pastures. We can literally touch the carousel of history.

To make things even more interesting, the Ptolemy's Serbs (Sorbs) in the 1st c. AD lived along the Itil/Volga river, they belonged to the Kangar tribes (agriculture was, and still is, impossible in the Itil/Volga steppes, only local gardening and nomadic pastoralism could be viable), and that was the area from where the Türkic Kaganate kicked out the Avars in 552 AD. And the Avars migrated to the particular area ruled by nothing less than the Sorbs from the banks of the Itil/Volga. Nobody knows what the Slavs were called in the 5th c., but at that time we already get them as Sorbs advancing into the Germanic lands. And later, the Kangars (Petchenegs/Patsinaks in the Slavic historiography) migrated, and they too moved in into the same northern Hungary and Bohemia area, and we know them again as Serbs and Horvats (Croats). And again we know them in that area as ethnically Slavs, by that time (9th c.) the name Slavs has already been established. Their language and name-changing scenario are exactly the same as for the Slavic Bulgars, Slavic Croats, Slavic Russians, Fennic Hungarians and Ossetian Digors.

Here is a tunnel-vision peek into Khazar genetic history from R1b1 aspect:

The subclade R1b1-L278/R1b1* sheds light on one of the most interesting and puzzling

pages of the European history. The Hebrew Ashkenaz (pl. Ashkenazim) referred to the Scythians

Askuzes/Ishkuzes, the name which renders the Türkic As-kiji (As-people) or As-guzes (As-tribe), a

transparent designation of the Türkic tribe of Ases (Ch. Yuezhi/Yueji 月支, possible compound of Hui/Yu

+ zhou 肉; the Ch. appellation Sui/Hui/Yui/Yu denotes Uigurs and was suggested to denote the Usun/Wusun

ancestors of the modern Uisyns). However, in Biblical Hebrew, Ashkenaz is a generic name for the

Türkic tribes independent of the tribal affiliation, and as such it was applied to the Khazars.

Life in the Khazar Kaganate was far from carefree, and religious turmoil was not any better than the political, ethnic, or military turmoils. Initially Tengrian, the core population has divided into interspersed religious fractions, after the fall of the Kaganate and the start of the ethnic-religious persecution the descendents of the converts to Judaism were finding themselves alien and defenseless. The Jewish Türks largely dispersed, joining various established Jewish communities, and establishing across the Medieval Europe a category called in Hebrew Ashkenazim. Fortunately for them, Europe was divided into uncounted number of independent and quasi-independent principalities, and some of them welcomed refugees as monetary and intellectual capital. Naturally, the Ashkenazim boys carried the Y-DNA of their ultimately Türkic forefathers, but their closer forefathers came from a hodgepodge of the Khazar Kaganate Türkic tribes that spun off millenniums earlier, and had millenniums of independent development, admixtures, and linguistic and historical evolution.

Khazars were an offshoot of the Bulgars, possibly sharing common genetics. The Khazars, like Bulgars, were identified with the ancient tribe of Ases. On the genetic tree, Khazars and Bulgars would likely constitute few distinct paired branches. A separate main branch of Khazars would be that of the Suvars/Savirs/Severyans, a second-largest Kaganate's majority, who had their own history and likely distinct genetic profile. The specific Bulgar clades should have survived among the the Türkic ethnicities in the Danube Bulgaria; the specific Savir clades should have a demographical peak in the vicinity of the Desna river, from Chernigiv to Kursk, among the Ukrainian and Russian populations. These subclades should show up on the exclusively Ashkenazi DNA tree, with allocation between Bulgar and Savir branches in accordance with the Danube Bulgaria/Chernigiv results.

On a deeper level, the initial appearance of the Bulgars and Huns in the Eastern Europe were likely unrelated events, the Huns migrating from the north, from the Aral and upper Itil/Volga area, and Bulgars migrating from the south, from the Bactria/Tocharistan, or the modern eastern Turkmenistan and southern Uzbekistan. They likely became the Hunno-Bulgars already in the Eastern Europe. A presence of the identical subclades in the southern Uzbekistan and the dispersal east and west of it would help to identify the Bulgar branch, and thus help to identify the Savir branch. The Savir branch should have elevated level of remnants in the vicinity of Dagestan. The number 5800 ybp (common ancestor) is quite significant in that respect, separating the Bulgar and Savir branches 2000 years prior to the Savirs/Subars' showing up in the Babylonian records in 23rd c. BC. And 28 centuries later, when Bulgars and Savirs have reunited, they spoke languages of the same Ogur family, apparently still mutually comprehensible.

Not all Ashkenazim originated as Khazar subjects. Some may have quite different origin, like those that joined the Jewish communities from other Türkic lands (N.-E. Europe, Balkans, etc.), later newcomers from the Kipchak Khanate, Persian Jews via Caucasus, Iberian Jewish refugees, and the like, or may have gained their nickname by their association with the Ashkenazi communities. The breakdown supplied by E.Elhaik (Fig. 6.) sheds a valuable light on the Ashkenazim composition.

Following are excerpts from an expert review by A.Klyosov, dealing with the study on a professional level (Anatoly A. Klesov, Ostensibly Khazar origin of Ashkenazi Jews. Analysis of Eran Elhaik article “The missing link of Jewish European ancestry: contrasting the Rhineland and the Khazarian hypotheses”//Genome Biology and Evolution, December 14 , 2012 //Proceedings of the Academy of DNA Genealogy, Volume 6, No. 3, March 2013, http://aklyosov.home.comcast.net. The bottom line of the review - Khazars have absolutely nothing to do with subject of the study:

“...The author set out to identify the “Khazar footprint” and its connection with the genome of the European Ashkenazi Jews. For that, he proceeded from two totally superfluous assumptions. First - that Khazars ostensibly lived in the Caucasus, and therefore they should have Caucasian genes. Second - because they were Jews, and eventually Jews moved to Europe, the genes moved with them to Europe. And thus, if the Caucasus genome is present in the Ashkenazi genome, it is a Khazar trail, and that is a proof of the starting position. A more muddled situation simply can not be imagined. The fact is that half of the eastern and north-eastern Caucasus has haplogroups J1 and J2, which are not directly related to the Jews, except that they are the same old lines as those of the Jews. They are not Jewish DNA lines. But the lines (J1 and J2) are the same, and of course, in the genome they have many of the same mutations as those of the Jews. Khazars have absolutely nothing to do with it. Irrespective of the Khazars, the genomes of many Caucasians and Jews are alike, and the beginning of the similarity ascends to the pre-Jewish time. Naturally, the author of the article found this similarity, and 90% of his article at length and tiresomely, with many repetitions, tells of the ostensibly Khazar genome, the direction of their alleged migration, and that the author's claimed discovery (with emphasis that the evidence for the Khazar's genome is found for the first time) demonstrates that the Ashkenazi Jews are not of European origin (Rhine hypothesis), but of the Khazar origin (Khazar hypothesis), and precisely that is demonstrated in the article....

...Is it really so hard to figure out that the similarity of Caucasians' and Jews' genomes may have other causes than through the Khazars? Is it so hard to have a look at the haplogroups of the Caucasians, and compare them with the haplogroups of the Jews? The Caucasians have all the major haplogroups of the Ashkenazim - J1, J2, G2, R1b, but each one has its own history, distinct from the history of the Jews...

This cited article should be rewritten, without a single word about the Khazars. That would be a good article.

...In short, in respect of the Khazars the article is incorrect, and absolutely does not solve the Khazar issue. But the material is instructive on how not to stage experiments if a fallacious question is posed from the beginning...

...Because the authors of the article did not have any Khazar remains or their descendants, instead were used biological materials of European and Caucasian populations. In the study, the Caucasian Georgians and Armenians have been postulated as proto- Khazars... From this Khazar mixture, according to the author, came out the Khazars, the Georgians, and Armenians....

...It did not occur to the author that Jews could have received different haplogroups not from the Khazars. For example, the Jewish haplogroup R1a is clearly not the from the Khazars, it is about 4 thousand years old, and most likely hails from the Near East... (Note that the Türkic Khazars were even more likely to inherit this 4,000 years old R1a haplogroup from the same Türkic Ashkenaz-Scythians than the ancient Jews). The Jewish haplogroup R2 is clearly not from the Khazars, it is only 500 years old. Perhaps it hails from Gypsies... I repeat, still remains unclear, how come that the German Jews (Rhine hypothesis) could be genetically homogeneous (or close), when originally they came from the Near East, scattered over Persia, Byzantium, Assyria, Mediterranean, and traversing Europe to get to the Germany. Anyway, the author has a mass of such conventions, approximations, and assumptions... In other words, it makes no sense to seek faults with the author on such details, when anyway he resolved the problem fundamentally wrong. That is he has not resolved it...

...For the first task of the study, the author set out to show that the Rhine and the Khazar hypotheses would in fact produce different ancestral patterns. And there starts the author's acrobatics. For a start and for example, he decided to find the genetic admixture between Palestinians and six Caucasian and Eurasian populations (Russians, Turks, Armenians, Georgians, Lezgins, and Adyges), as a negative control taking the African San people. Generally, the start is quite funny, because all these six populations have considerably overlapping male haplogroups... All of these six populations have the haplogroups R1a, R1b, G2a, J1, J2 , and so on, naturally at different extents. The absence of admixture simply could not happen there, because these are the same haplogroups. That is, the SNPs are also the same, and these SNPs are pulling along other related SNPs of the populations. But the author continued acrobatics. He pointed to the Armenians and Georgians, with their admixture with the Palestinians at 0.0019, and explained that since Armenians and Georgians split with the Turks 600 generations ago (citation without any explanation), or about 15-18 thousand years ago (???), in that admixture the Jewish portion can not be present, because Jewish admixture would have been recent. That is, this admixture is “territorial” and not “Semitic”. As the author wrote, “the similarities between European Jews and Caucasians is not caused by common Semitic ancestors”... In reality, the proportion of “admixture” is defined by the interplay of the haplogroups, among which J1 and J2 are also at the Jews, and likewise G2a, and R1a, and R1b, and so on... To separate “territory” and “Semitic” does not make much sense. All the author's pirouettes produce absolutely nothing. But in one aspect the author is right, the similarity between European Jews and Caucasians is not caused by common Semitic ancestors. But that is for completely different reasons, because Caucasians do not have them (excepting the Mountain Jews), but they have the haplogroups J1 and J2. And the Khazars have absolutely nothing to do with that.

Then the author went on to the “multicomponent analysis” graphics... Since the haplogroups J1 and J2 are present in all three populations, and in large proportions, the final disposition must by driven by the balance of haplogroups with no or small presence in some of the three populations. For example, European Jews have large proportions of the haplogroups G2a and R1b, large proportion of them is in the Caucasus (and they have nothing to do with the Khazars, these are ancient haplogroups), but the Near East has little of them. So, it can be expected that the European Jews will fall closer to the Caucasians, but not to the Near East, although the final picture would depend on the complicated interplay of the SNPs. The author reasoned: If the Rhine hypothesis is correct, the European Jews will fall closer to the Near East, and if the Khazar hypothesis is correct, they will fall closer to the Caucasus. We have, however, already seen that the Khazars again have nothing to do with that... And so it happened. More than 70% of the European Jews, and almost all Eastern European Jews on the chart fell closer to the Caucasians, and namely to the Georgians, Armenians, and Azerbaijani Jews. Here, exclaims the author, this is a strong proof of the Khazar hypothesis. Moreover, exclaims the author, migrations of the Caucasians to Europe prior to the time of the Khazar empire are unknown, so then it were the Khazars who migrated, and brought the Caucasian SNPs to Europe together with the Jews. This is of course laughable. The Jews themselves brought their haplogroups J1, J2, R1a, G2a, R1b to Europe (and received haplogroups from other Europeans, like in the Near East they received R1a about 4000 years ago) (4000 years is the time to a common ancestor, not the time of receipt), and the same haplogroup from old times, namely at least 6,000 years ago, were present in the Caucasus. Therefore Caucasians did not have to venture anywhere, they had all of this since ancient times. And had it without the Khazars. They had it in parallel with the Jews... The methodology is wrong in principle...

Again and again, the author reiterates that the Rhine hypothesis can not explain the genomic similarity between Jews and Caucasians, but can explain similarity with the Khazars. Here we have to state again that that had nothing to do with the Khazars. These haplogroups came to the Caucasus from the Near East long before the Jews, and likewise they came to the Jews too, and therefore a deep similarity exists... Here, I quote the author: “Although the European Jews form a cluster with Caucasian populations, the Eastern and Central European Jews share a large cluster with Western European and Middle Eastern populations”. Well, naturally, they have to share the “large cluster”, since the haplogroups are again the same. There is no “either- or”, everything is, again, determined by the interplay of the proportion of the haplotypes and SNPs in the population, and the mosaic can be very different. But since the author introduces many degrees of freedom into interpretation, anything can be explained. The similarity of Jewish SNPs with the Western Europe is explained by introduction into the game of the “Greco -Roman Jews”, with “Israel proto-Jews”, and “Mesopotamian Jews”.

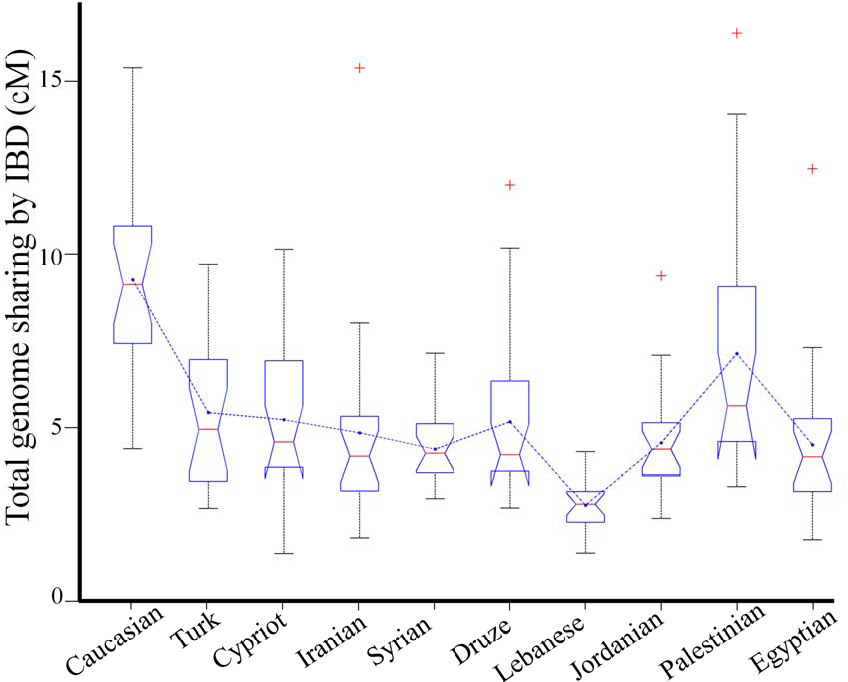

All other acrobatics in the article are of the same character - their basis rests on the haplogroup similarity between the Caucasians and European Jews, call or not to call them Ashkenazim. As a measure of similarity the author uses the so-called IBD (identity by descent), where the average similarity is compared by the “length” of the genomic regions. It turned out that in this case also, the length of the average similarity between the European Jews and Caucasians is 9.5 cM, and between the same Jews and the Palestinians only 5.5 cM. Again, the author attributes the reason to the Khazars, while it is the similarity of the haplogroups between the Ashkenazim and Caucasians. Again, that has nothing to do with the Khazars...”

With such a preface, enjoy the Ashkenazim story. You do not need to read technicalities, after Introduction you may go directly to the Discussion on page 16.

The posting's notes and explanations, added to the text of the author and not noted specially, are highlighted in blue font, shown in (blue italics) in parentheses and in blue boxes. Page numbers are shown at the end of the page in blue.

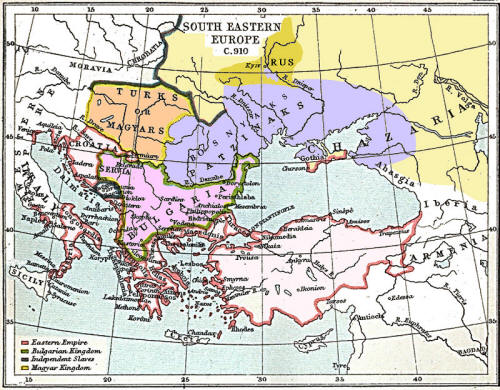

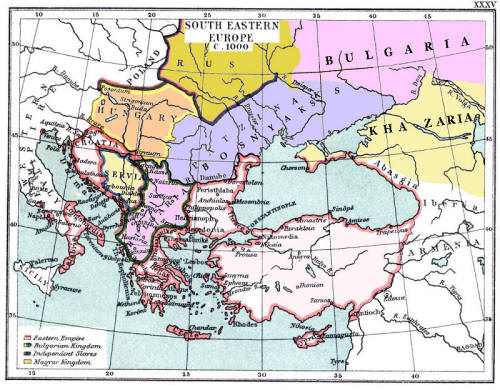

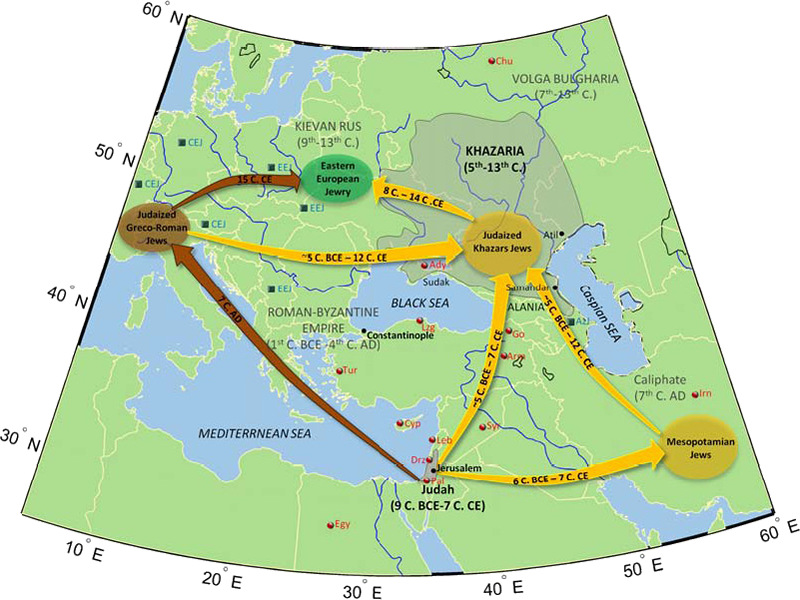

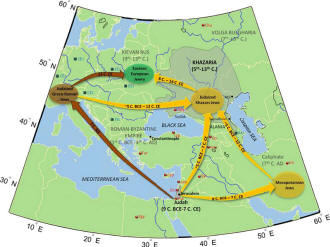

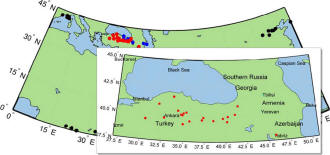

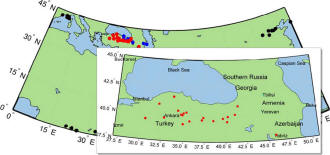

| Figure 1. Map of Eurasia. A map of Khazaria and Judah is shown with the state of origin of the studied groups. Eurasian Jewish and non-Jewish populations used in all analyses are shown in square and round bullets, respectively (see Table S3). The major migrations that formed Eastern European Jewry according to the Khazarian and Rhineland Hypotheses are shown in yellow and browns, respectively. |

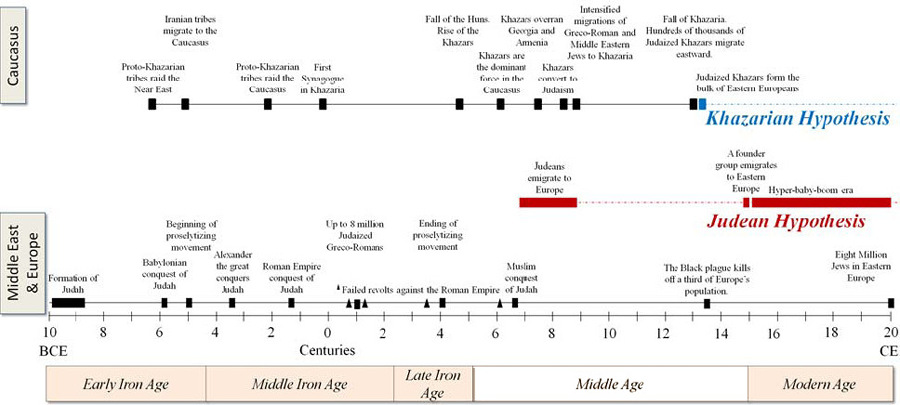

| Figure 2. An illustrated timeline for the relevant historical events. The horizontal dashed lines represent controversial historical events explained by the different hypotheses, whereas solid black lines represent undisputed historical events. |

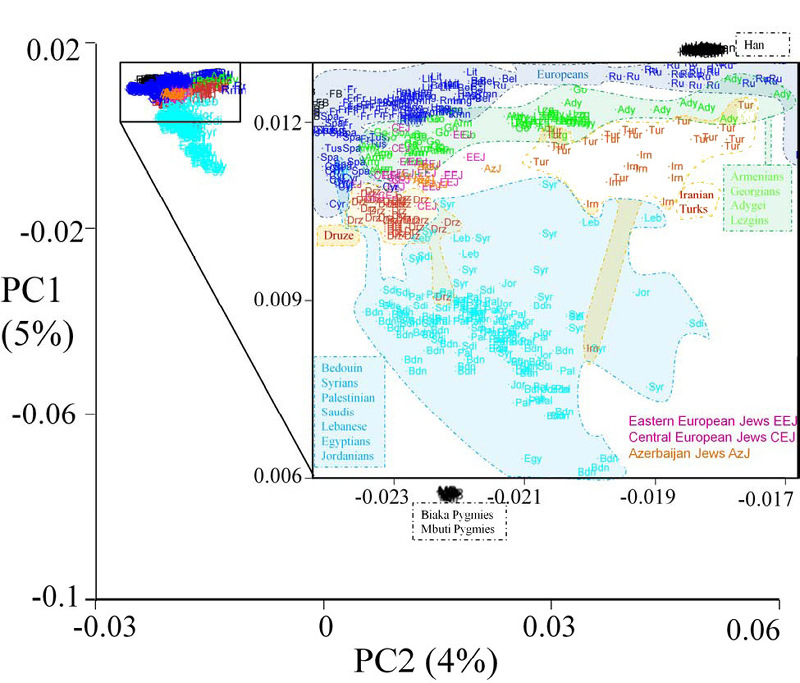

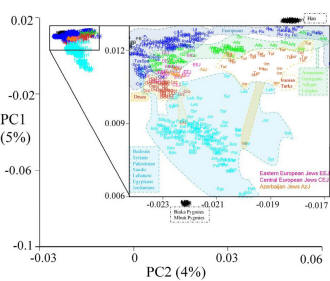

| Figure 3. Scatter plot of all populations along the first two principal components (Table S3). For brevity, we show only the populations relevant to this study. The inset magnifies Eurasian and Middle Eastern individuals. Each letter code corresponds to one individual. A polygon surrounding all of the individual samples belonging to a group designation highlights several population groups. |

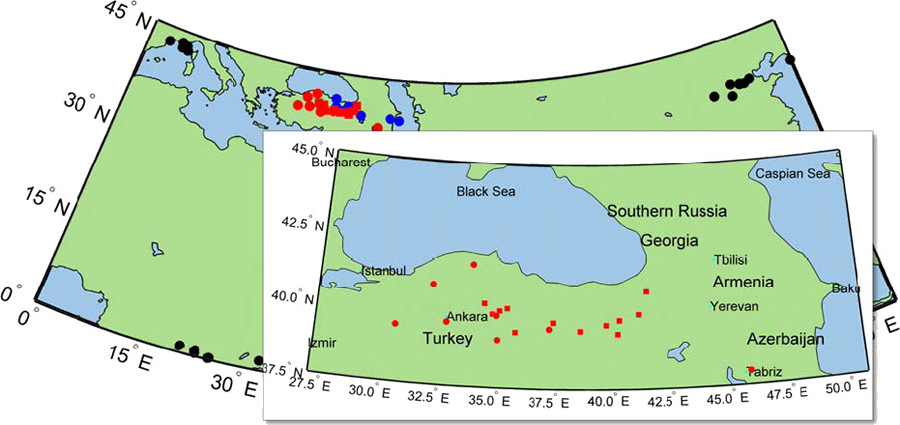

| Figure 4. Biogeographical origin of European Jews. First two principal components were calculated for Pygmies, French Basque, Han Chinese (black), Armenians (blue), and Eastern or Central European Jews (red) - all of equal size. PCA was calculated separately for Eastern and Central European Jews and the results were merged. Using the first four populations as training set, Eastern (squares) and Central (circles) European Jews were assigned to geographical locations by fitting independent linear models for latitude and longitude as predicted by PC1 and PC2. Each shape represents an individual. Major cities are marked in cyan. |

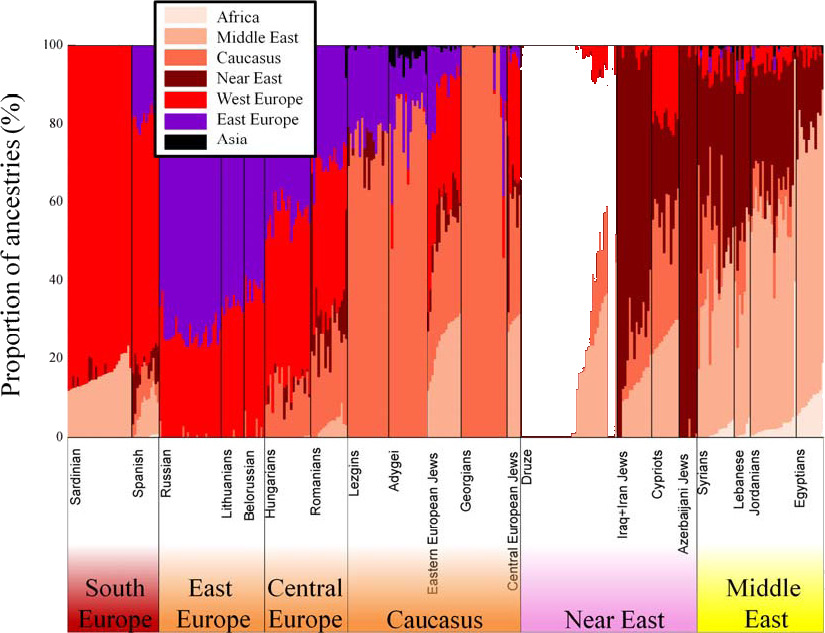

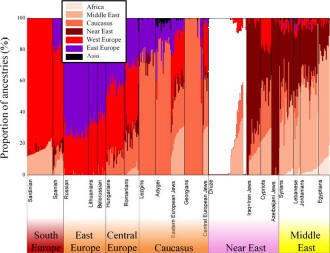

| Figure 5. Admixture analysis of Caucasus, Near Eastern, and Middle Eastern populations. The x-axis represents individuals from populations sorted according to their ancestries and arrayed geographically roughly from North to South. Each individual is represented by a vertical stacked column (100%) of color-coded admixture proportions of the five ancestral populations. Here, the three Netherland Jews were grouped with Eastern European Jews due to their shared similarity. |

| Figure 6. Proportion of total IBD sharing between European Jews and different populations. Populations are sorted by decreasing distance from the Caucasus. The maximal IBD between each European Jew and an individual from each population are summarized in box plots. Lines pass through the mean values. |

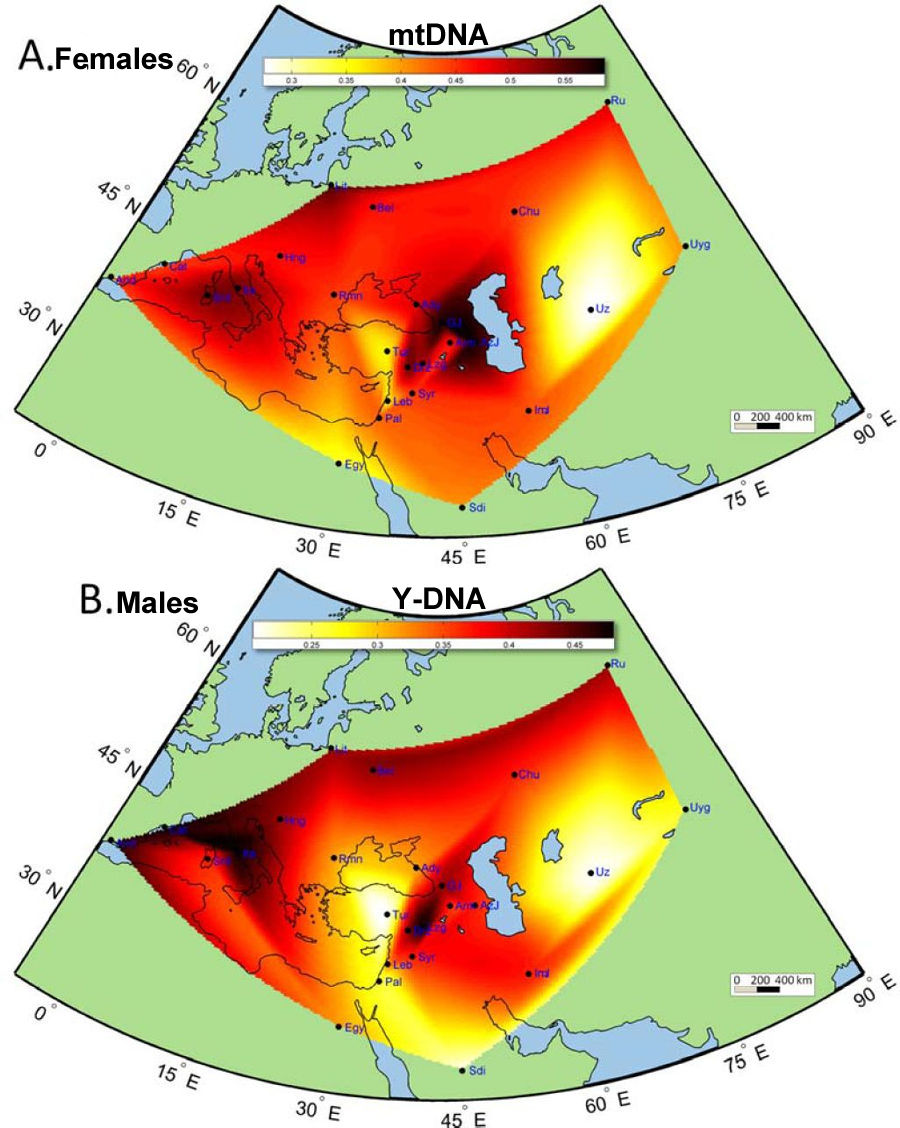

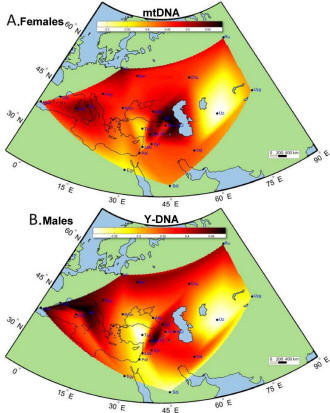

| Figure 7. Pairwise genetic distances between European Jews and other populations measured across a) mtDNA and b) Y-chromosomal haplogroup frequencies. The values of 1- δxy are color coded in a heat map with darker colors indicating higher haplogroup similarity with European Jews. |

| Table 1. Genetic distances (ASD) between regional and continental Jewish communities (left panel) and between regional Jewish communities and their neighboring populations, Caucasus, and Middle Eastern population (right panel). Bold entries are significantly smaller throughout each panel. The geographically nearest non-Jewish population were considered neighboring populations. The distances in the last two columns are between a Jewish and one Caucasus population (Armenians or Georgians) or Middle Eastern population (Palestinians, Bedouins, or Jordanians) that exhibited the lowest mean ASD. |

Contemporary Eastern European Jews comprise the largest ethno-religious aggregate of modern Jewish communities, accounting for nearly 90% of over 13 million Jews worldwide (United Jewish Communities 2003). Speculated to have emerged from a small Central European founder group and maintained high endogamy, Eastern European Jews are considered invaluable subjects in disease studies (Carmeli 2004), although their ancestry remains debatable among geneticists, historians, and linguists (Wexler 1993; Brook 2006). Because correcting for population structure and using suitable controls are critical in medical studies, it is vital to test the different hypotheses pertaining to explain the ancestry of Eastern European Jews. One of the major challenges for any hypothesis is to explain the massive presence of Jews in Eastern Europe, estimated at eight million people at the beginning of the 20th century. The two dominant hypotheses depict either a sole Middle Eastern ancestry or a mixed Middle Eastern-Caucasus- European ancestry.

The “Rhineland Hypothesis” envisions modern European Jews to be the descendents of the Judeans – an assortment of Israelite-Canaanite tribes of Semitic origin (Figures 1-2) (Supplementary Note). It proposes two mass migratory waves: the first occurred over the next two hundred years after the Muslim conquest Palestine (638 CE) and consisted of devoted Judeans who left Muslim Palestine for Europe (Dinur 1961; Sand 2009). It is unclear whether these migrants joined the existing Èóäîèçèðîâàí Greco-Roman communities and the extent of their contribution to the Southern European gene pool. The second wave occurred at the beginning of the 15th century by a group of 50,000 German Jews who migrated eastward and ushered an apparent hyper-baby-boom era for half a millennia affecting only Eastern Europe Jews (Atzmon et al. 2010). The annual growth rate that accounted for the populations’ rapid expansion from this small group was estimated at 1.7-2% (Straten 2007), twice the rate of any documented babyboom period and lasting 20 times longer. This growth rate is also one order of magnitude larger than that of Eastern European non-Jews in the 15th-17th centuries.4

The Rhineland Hypothesis predicts a Middle Easter ancestry to European Jews and high genetic similarity among European Jews (Ostrer 2001; Atzmon et al. 2010; Behar et al. 2010). The competing “Khazarian Hypothesis” considers Eastern European Jews the descendants of ancient and late Judeans who joined the Khazars, a confederation of Slavic, Scythian, Sabirs, Finno-Ugrian, Alan, Avars, Iranian, and Turkish tribes who formed in the northern Caucasus one of most powerful and pluralistic empires during the late Iron Age and converted to Judaism in the 8th century CE (Figures 1-2) (Polak 1951; Brook 2006; Sand 2009).

| Listing of tribes is funny, it appears to be in a reverse order. Khazars took over supremacy from

the Bulgars, who established an independent state Great Bulgaria in 630 AD, headed by

Khan Kurbat (e.g., see

Runciman S Bulgar Empire). Predominantly, population of the Great Bulgaria was Türkic,

including Bulgars (majority), Alans, Savirs, Scythians, and Avars. The Slavs were settled

only on the western border of the Great Bulgaria, and later also quartered in Bashtu (future

Kyiv) as a standing infantry unit heading the Slavic peasant militia. No Iranian tribes

are known in the Bulgar or Khazar Kaganate. Magyars in the Levedia were small

Finno-Ugrian minority, among the tributary populations were Slavic and Fennic tribes. The

Khazar takeover was a proxy for the Western Türkic

Kaganate, which re-established the conquest made in 552 AD. Until the demise of the

Western Türkic

Kaganate, Khazaria was ruled by a viceregent of the Western Türkic

Kaganate, who in 660 proclaimed himself an independent Kagan. After 660, Khazaria

attracted numerous settlers from numerous ethnicities, including Slavic migrants, but

they remained a minor minority in the Bulgarian state headed by the leading tribe of

Khazars under aegis of the Türkic Ashina Kagan.

Listing populations in reverse order reflects the preconceptions or blind ignorance of the sources at author's disposal. The demographical aspect of the Khazar state is given by the size of the Khazar army at 300,000 riders, implying 300,000 families and 1.5 mln of nomadic population. The nomadic character of the army is attested by its mobility and nearly instantaneous mobilization upon the Arab invasion, unimaginable for peasant infantry of the Caucasian mountaineers, Slavic peasant infantry, and Fennic hunter-gatherer iinfantry. If the data of the Arab sources is greatly exaggerated, by a factor of 2-3, that still leaves 500,000 to 1,000,000 Türkic nomadic families, predominantly Bulgars. |

The Khazarian, Armenian, and Georgian populations forged from this amalgamation of tribes (Polak 1951), followed by high levels of isolation, differentiation, and genetic drift in situ (Balanovsky et al. 2011).

| The postulation of Balanovsky et al., 2011, does not have any merits, and contradicts history. On 100-year Arab-Khazar war, and displacements caused by it, see L.Gmyrya Caspian Huns. The wars reverberated across the whole state, affecting the theater of operations, population, economy, and demographics. |

The population structure of the Judeo-Khazars was further reshaped by multiple migrations of Jews from the Byzantine Empire and Caliphate to the Khazarian Empire (Figure 1). The collapse of the Khazar Empire followed by the Black Death (1347-1348) accelerated the progressive depopulation of Khazaria (Baron 1993) in favor of the rising Polish Kingdom and Hungary (Polak 1951).

The newcomers mixed with the existing Jewish communities established during the uprise of

Khazaria and spread to Central and Western Europe. The Khazarian Hypothesis predicts that European

Jews comprise of Caucasus, European, and Middle Eastern ancestries and is distinct from the

Rhineland Hypothesis in the existence of a large genetic signature of Caucasus populations. Because

some Eastern European Jews migrated west and admixed with the neighboring Jewish and non-Jewish

populations they became distinct from the remaining Eastern European Jews. Therefore, different

European Jewish communities are expected to be heterogeneous. Alternative hypotheses, such as the

“Greco-Roman Hypothesis” (Zoossmann-Diskin 2010), were also proposed to explain the origins of

European Jews; however, they do not explain the massive presence of Eastern Europeans Jews in the

20th century and therefore were not tested here. Many genetic studies attempting to settle these

competing hypotheses yielded inconsistent results.

5

Some studies pointed at the genetic similarity between European Jews and Middle Eastern populations such as Palestinians (Hammer et al. 2000; Nebel et al. 2000; Atzmon et al. 2010), while few pointed at the similarity to Caucasus populations like Adygei (Behar et al. 2003; Levy-Coffman 2005; Kopelman et al. 2009), and others pointed at the similarity to Southern European populations like Italians (Atzmon et al. 2010; Zoossmann-Diskin 2010). Most of these studies were done in the pre-genomewide era, using uniparental markers and included different reference populations, which makes it difficult to compare their results. More recent studies employing whole genome data reported high genetic similarity of European Jews to Druze, Italian, and Middle Eastern populations (Atzmon et al. 2010; Behar et al. 2010). Motivated by the recent availability of genome-wide data for key populations, the current study aims to uncover the ancestry of Eastern and Central European Jews by contrasting the Rhineland and Khazarian Hypotheses. These hypotheses were tested here by comparing the biogeographical genetic profile of European Jews with indigenous Middle Eastern and Caucasus populations using a wide set of population genetic tools including principal component analyses (PCAs), identification of the biogeographical origins of European Jews, admixture, identity by descent (IBD), allele sharing distance (ASD), and finally by comparing haplogroup frequencies of Y and mtDNA.

As the Judeans and Khazars have been vanquished and their remains have yet to be sequenced, in accordance with previous studies (Levy-Coffman 2005; Kopelman et al. 2009; Atzmon et al. 2010; Behar et al. 2010), contemporary Middle Eastern and Caucasus populations were used as surrogates. Palestinians were considered Proto-Judeans because they shared a similar linguistic, ethnic, and geographic background with the Judeans and were shown to share common ancestry with European Jews (Bonné-Tamir and Adam 1992; Nebel et al. 2000; Atzmon et al. 2010; Behar et al. 2010). Similarly, Caucasus Armenian and Georgians were considered Proto-Khazars because they emerged from the same cohort as the Khazars (Polak 1951; Dvornik 1962; Brook 2006).

| To genetically equate the Türkic Khazars with the Armenian and Georgians is like equating Innuits with French Canadians. Such a premise would have defeated the objective of the whole study, if not for the genetic data that speaks for itself. However, The Disscussion and Conclusions may need to be corrected terminologically, to accoun for the critical nonsensical presumption. |

Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) analyses corroborated the genetic similarity between Armenians and Georgians (i.e. between the Armenian and Georgian females) (Behar et al. 2010) and estimated their approximate divergence time from the Turks and Iranians 600 and 360 generations ago, respectively (Schonberg et al. 2011) (i.e. 15,000 and 9,000 ybp, the dates that do not make any sense).

| All that mtDNA analysis shows is the the similarity between the Armenian and Georgian women, attesting to one thing only: that Armenian and Georgian men married local women, and thus, gained a common genetic heritage. It is true that the Khazar men may have taken in the local women as wives, whether their Bersula was west of the Caspian or east of it, and in the Caucasus they had a choice of the Caucasus women, but to equate them with Armenian and Georgian women is no reason. |

Although both the Rhineland and Khazarian Hypotheses depict a Judean ancestry and are not mutually exclusive, they are well distinguished, as Caucasus and Semitic populations are considered ethnically and linguistically distinct (Patai and Patai 1975; Wexler 1993; Balanovsky et al. 2011). Jews, according to either hypothesis, are an assortment of tribes who accepted Judaism and maintained it up to this date and are, therefore, expected to exhibit certain heterogeneity with their neighboring populations. Because, according to both hypotheses, Eastern European Jews arrived in Eastern Europe roughly at the same time (13th and 15th centuries), we assumed that they experienced similar low and fixed admixture rates with the neighboring populations, estimated at 0.5% per generation over the past 50 generations (Ostrer 2001). These relatively recent admixtures have likely reshaped the population structure of all European Jews and increased the genetic distances from the Caucasus or Middle Eastern populations. Therefore, we do not expect to achieve perfect matching with the surrogate populations but rather to estimate their relatedness.

Discussion

Eastern and Central European Jews comprise the largest group of contemporary Jews,

accounting for nearly 90% of over 13 million worldwide Jews (United Jewish Communities

2003). Eastern European Jews made over 90% of European Jews before World War II. Despite

of their controversial ancestry, European Jews are an attractive group for genetic and

disease studies due to their presumed genetic history (Ostrer 2001). Correcting for

population structure and using suitable controls are critical in disease studies, thus it

is vital to determine whether European Jews are of Semitic, Caucasus, or other ancestry.

Eastern and Central European Jews comprise the largest group of contemporary Jews,

accounting for nearly 90% of over 13 million worldwide Jews (United Jewish Communities

2003). Eastern European Jews made over 90% of European Jews before World War II. Despite

of their controversial ancestry, European Jews are an attractive group for genetic and

disease studies due to their presumed genetic history (Ostrer 2001). Correcting for

population structure and using suitable controls are critical in disease studies, thus it

is vital to determine whether European Jews are of Semitic, Caucasus, or other ancestry.

Though Judaism was born encased in theological-historical myth, no Jewish

historiography was produced from the time of Josephus Flavius (1st century CE) to the

19th century (Sand 2009). Early German historians bridged the historical gap simply by

linking modern Jews directly to the ancient Judeans (Figure 1); a paradigm that was quickly

embedded in medical science and crystallized as a narrative.

17

Many have challenged this narrative (Koestler 1976; Straten 2007), mainly by showing that a sole Judean ancestry cannot account for the vast population of Eastern European Jews in the beginning of the 20th century without the major contribution of Judaized Khazars and by demonstrating that it is in conflict with anthropological, historical, and genetic evidence (Dinur 1961; Patai and Patai 1975; Baron 1993).

With uniparental and whole genome analyses providing ambiguous answers (Levy-Coffman 2005; Atzmon et al. 2010; Behar et al. 2010), the question of European Jewish ancestry remained debated mainly between the supporters of the Rhineland and Khazarian Hypotheses. The recent availability of genomic data of Caucasus populations (Behar et al. 2010) allowed testing the Khazarian Hypothesis for the first time and prompted us to contrast the Rhineland and Khazarian Hypotheses. To evaluate the two hypotheses, we carried out a series of comparative analyses between European Jews and surrogate Khazarian (i.e. Armenian-Georgian) and Judean (i.e. Palestinian) populations posing the same question each time: are Eastern and Central European Jews genetically closer to Caucasus or Middle Eastern populations? We emphasize that these hypotheses are not exclusive and that some European Jews may have other ancestries.

Our PC, biogeographical estimation, admixture, IBD, ASD, and uniparental analyses were consistent in depicting a Caucasus ancestry for European Jews. Our first analyses revealed tight genetic relationship of European Jews and Caucasus populations and pinpointed the biogeographical origin of European Jews to the south of Khazaria (Figures 3,4).

Fig. 3 |

Fig. 4 |

|---|

Our later analyses yielded a complex multi-ethnical ancestry with a slightly dominant Near Eastern-Caucasus ancestry, large Southern European and Middle Eastern ancestries, and a minor Eastern European contribution; the latter two differentiated Central and Eastern European Jews (Figures 4, 5 and Table 1).

Fig. 4 |

Fig. 5 |

|---|---|

Table 1 |

|

While the Middle Eastern ancestry faded in the ASD and uniparental analyses, the Southern European ancestry was upheld probably attesting to its later time period (Table 1 and Figure 7).

We show that the Khazarian Hypothesis offers a comprehensive explanation to the results,

including the reported Southern European (Atzmon et al. 2010; Zoossmann-Diskin 2010) and Middle

Eastern ancestries (Nebel et al. 2000; Behar et al. 2010).

18

By contrast, the Rhineland Hypothesis could not explain the large Caucasus (i.e. Armenian and Georgian) component in European Jews, which is rare in Non-Caucasus populations (Figure 5) and the large IBD regions shared between European Jews and Caucasus populations (Armenians and Georgians) attesting to their common origins. A major difficulty with the Rhineland Hypothesis, in addition to the lack of historical and anthropological evidence to the multi-migration waves from Palestine to Europe (Straten 2003; Sand 2009), is to explain the vast population expansion of Eastern European Jews from 50 thousand (15th century) to 8 million (20th century). This growth could not possibly be the product of natural population expansion (Koestler 1976; Straten 2007), particularly one subjected to severe economic restrictions, slavery, assimilation, the Black Death and other plagues, forced and voluntary conversions, persecutions, kidnappings, rapes, exiles, wars, massacres, and pogroms (Koestler 1976; Sand 2009). Such an unnatural growth rate (1.7-2% annually) over half a millennia, affecting only Jews residing in Eastern Europe is commonly explained by a miracle (Atzmon et al. 2010). Unfortunately, this divine intervention explanation poses a new kind of problem - it is not science. Our findings reject the Rhineland Hypothesis and uphold the thesis that Eastern European Jews are Judeo-Khazars in origin. Further studies are necessary to confirm the magnitude of the Khazars demographic contribution to the demographic presence of Jews in Europe (Polak 1951; Dinur 1961; Koestler 1976; Baron 1993; Brook 2006).

The most parsimonious explanation for these findings is that Eastern European Jews are of Judeo-Khazarian ancestry forged over many centuries in the Caucasus. Jewish presence in the Caucasus and later Khazaria was recorded as early as the late centuries BCE and reinforced due to the increase in trade along the Silk Road (Figure 1), the decline of Judah (1st-7th centuries), and the uprise of Christianity and Islam (Polak 1951). Greco-Roman and Mesopotamian Jews gravitating toward Khazaria were also common in the early centuries (of Khazaria) and their migrations were intensified following the Khazars’ conversion to Judaism (Polak 1951; Brook 2006; Sand 2009).

| The idea of a state religion was foreign to Khazaria and any other Türkic confederation. Anyone

familiar with the American and Türkic religious tolerance would immediately recognize the common

origin. Khazaria was only a signal case of the Türkic religious tolerance, it is one side of being open

to new ideas, endemic and honed in constant dealing with numerous various peoples, innate to the

nomadic economy. That tradition

continued into the Mongol Epoch, and is well documented. Religious tolerance is typical to all

non-dogmatic religions, only the advent of Islam and Christianity

changed that attitude, and even then it was fanned up by political adventurists who tried to use

religious divisions to advance their ambitions, changing little the natural tolerant attitudes of the

population. The general religious policy of the Türkic rulers of the pre-Islam time was a respect

and tolerance of all religious beliefs. Conversion could only be private and individual, Tengriism

is a non-hierarchical syncretic religion, open to any external influence, and religious tolerance is

a backbone of syncretism. Since it is based on personal reincarnation, it is inherently personal

religion, free of dogmas and intercessors. Nobody with a sane mind would abandon direct contact with

Almighty in favor of sweet-and-thunder talking middlemen. Thus, the first hurdle in conversion is

not the choice between scholastic dogmas, but a choice between the Almighty and middlemen

pretenders, with no chances for the middlemen. Tengriists could only perceive religion without

hierarchy, i.e. accept divinity without apparatus that claims to represent that divinity. Thus, the

reforms of the Khazar Kagan Obadia (799-809), the official acceptance of Judaism as a state

religion, was adorned with continued policy of religious tolerance. The bottom line: “Khazars” could not convert to Judaism, only the ruling elite could elect to convert, for whatever reasons, and many declined, initiating a period of religious fragmentation. The numerous ethnic groups of the state remained free to pursue their traditional religions, the state remained multi-denominational during all of its history. The loose tongues depict change of religion or switch between denominations as routine and easy step, akin to changing hats, while the subject is personal and individual communion with the Almighty and personal reincarnation at the will of the Almighty. The concept of “state religion” was totally alien to the people who could entreat directly to the Almighty in their own language anywhere and anytime. These facts are well-documented, and where they conflict with the modern “consensus”, they undermine the logic of pundits adopted in this study. |

The eastward male-driven migrations (Figure 7) from Europe to Khazaria solidified the exotic Southern European ancestry in the Khazarian gene pool (i.e. in the gene pool of modern Ashkenazi Jews), (Figure 5) and increased the genetic heterogeneity of the Judeo-Khazarsl (i.e. modern Ashkenazi Jews). The religious conversion of the Khazars encompassed all the Empire’s citizens and subordinate tribes and lasted for the next 400 years (Polak 1951; Baron 1993) until the invasion of the Mongols (Polak 1951; Dinur 1961; Brook 2006).

| This is an utter nonsense, scooped from unscrupulous informers, namely Polak, Baron, Dinur,

and Brook. First, the Romans led intensive campaigns in the Caucasus, involving exclusively male

armies quite compatible in size with the male populations of the countries and provinces they

traversed, and during military campaigns insemination of the local women is more then expected.

History did not leave us any demographic descriptions on the baby booms that blossomed as a result

of the Roman campaigns, but genetics does supply us with the evidence of their presence, which may

include those remaining behind, wounded, captured, and deserters. The genes

(Y-DNA marker), carried by the male offsprings, in the following centuries drifted around,

spreading the exotic Apennine genes far and wide. The Jewish population, an alien minority among the

local Caucasian peoples, must have been especially susceptible to violence and banditry of the

Roman armies' incursions and garrisons, and their later migrations carried the Apennine genes

everywhere where

the Jews migrated to. On top of that, the very same Bulgars settled in the Apennine peninsula on a few occasions, the Hunnic Germanic allies that settled in the Apennine peninsula could unwittingly carry and spread the Türkic genes, and the Celtic tribes that sucked Rome could leave genes of the same genetic line. What is taken as exotic Apennine may be a daily life of the Türkic people. More on that, see A.Klyosov comments in this posting. Secondly, the religious conversion of the Khazars did not encompass all of the Empire’s citizens and subordinate tribes, and did not last for the next 400 years. The majority of the Khazar population were ethnical Bulgars and Suvars, and neither one converted to Judaism. Bulgars converted to Islam, and by 922 Moslems constituted a majority of Bulgars, the balance remained Tengrian. Suvars remained Tengrian, and gradually converted to Christianity. The Fennic Mordva (Burtases) retained their Fennic religion, the Fennic northern tribes retained their Fennic religion, the Caucasus Alans first partially converted to Islam, then partially to Christianity, although Judaism made some inroads into the Alan royal court. Mishars converted to Islam, the northern Suvars defended their Tengriism, then succumbed to Islam in the 11th c. Some Slavs retained their religion, others became Christians. We know nothing of the Khazar ethnicity, but they were an insignificant minority in the Khazar Kaganate anyway. Attempts to Christianize Kayi, Suvars, and Huns in the Caucasus utterly failed, population revolted and expelled the Christian missionaries, but Agvans converted to Christianity, and remained Christian after the Arab conquest. Azeri were Islamicized with the Arab conquest. Kubars preferred to migrate with Magyars to retain their Tengriism. Akacirs were Tengrian at a time of Olga of Kyiv. Kangars (Bosnyaks) remained Tengrian, Oguzes converted to Islam still in the Middle Asia, some of them later converted to Christianity. Kyiv had Jewish quarter, Khazar quarter, and Slavic quarter. Itil had Jewish part, Christian part, and Islamic part. For most of the above groups, the dates and events of their conversion to organized religions are well known. Some Türkic groups, apparently mostly settled craftsmen and traders, converted to Judaism, of them we know sufficiently well only the Crimean Karaims. Later travelers noted some “sectarians” living amidst desolation in perpetual mourning, these likely were Jewish settlements amid the sea of nomadic pastoral tribes before their migration to join their co-religionists in the Caucasus, in the Middle Asia, or westward. The “religious conversion of the Khazars” is not even a lie, it is just a wild fantasy. Timeline of Khazar Kaganate

|

At the final collapse of their empire (13th century), the Judeo- Khazars fled to Eastern Europe and later migrated to Central Europe and admixing with the neighboring populations. Historical and archeological findings shed light on the demographic events followed the Khazars’ conversion. During the half millennium (740–1250 CE) of their existence, the Judeo-Khazars sent offshoots into the Slavic lands, such as (modern) Romania and Hungary (Baron 1993), planting the seeds of a great Jewish community to later rise in the Khazarian diaspora.

| As show the following maps, between the 8th c. and 11th c. of the existence of the Khazar

Kaganate, the Khazarian Jews had a choice of setting their trading post factorias in Avaria (8th c.),

Danube Bulgaria (8th -11th cc.), Bosnyak-Pachanakia (8th -10th cc.), Hungary (10th-11th cc.),

and Rus (9th-11th cc.). At the time, the modern Rumania was Danube Bulgaria, and Pannonia was in

Avaria, Bulgaria, and Hungary, all of them populated by a combination of Türkic people and

Slavs. The term Judeo-Khazars does nor mean Khazars of Judaic persuasion, it means Jews and Türkic converts to Judaism, the subjects of the Khazar polity. The ambiguity of the terminology allows to create a false impression that “Judeo-Khazars” were all ethnically Khazars. |

We hypothesize that the settlement of Judeo-Khazars in Eastern Europe was achieved by serial founding events, whereby populations expanded from the Caucasus into Eastern and Central Europe by successive splits, with daughter populations expanding to new territories following changes in socio-political conditions (Gilbert 1993). As a result, the Jewish communities along the Caucasus borders appear more heterogeneous than other Jewish communities (Table 1), assuming an even and low admixture rate. After the decline of their Empire, the Judeo-Khazars refugees sought shelter in the emerging Polish Kingdom and other Eastern European communities, where their expertise in economics, finances, and politics were valued. Prior to their exodus, the Judeo-Khazar population was estimated to be half a million in size, the same as the number of Jews in the Polish-Lithuanian kingdom four centuries later (Polak 1951; Koestler 1976).

| The same Polak who proposed that entire population of Khazaria adopted Judaism suggests totally unrealistic estimate of the Jewish migration. Comparing with demographic estimates for the other Eastern European inhabitants, the number of half a million appears to be grossly exaggerated. The Khazars proper in the 7th c. numbered about 20-50,000 people, it was a small Türkic tribe. The most numerous group in the Eastern Europe were Bulgars, which after a split into 5 fractions have a somewhat realistic assessment for 2 splinters, Itil Bulgars at 200,000, and Danube Bulgars at 50,000. Adding the Pannonia Bulgars, say 50,000, Caucasian Bulgars at 100,000, and the Bulgars scattered elsewhere in the Eastern Europe as 200,000, would total about 1 mln for the largest ethnic group of the land, or better than 50% of the total Eastern European population, which may reach 2 mln total. Other largest ethnic groups were Slavs, probably numbering 100,000 after Asparukh took away half of the Eastern European Slavic migrants to the Balkans, and Suvars, probably 100,000 at the most. In comparison, half a million Jews of Jewish and Türkic ancestry appear outrageous, exaggerated by orders of magnitude. A more realistic number would be 100,000 of total Khazarian Jews, with western migrants numbering half of that, or combined 50,000 over 3 centuries of migration. The effect of compound growth rate should be used in the demographic of immigration: every new wave adds to the absolute numbers, while maintaining the average rate of growth. Allowing for doubling of the population per century, i.e. the same rate of increase as among the neighbors, and the start of exodus in the 10th c., by the 15th c. the Central and Eastern European Jewry of the Eastern European refugees would reach 800,000, at which time they would accept an influx of the Ladino Jews numbering 50,000. In addition, the Central and Eastern European Jewry would include the local Central European Jews, who passed their Yiddish vernacular to all the newcomers, their number by the 15th c. may be accepted as 200,000, i.e. an equivalent of 10-20,000 in the 10th c. The estimate can and should be calibrated with the available data instead of relying on wild guess. |

Some Judeo-Khazars were left behind, mainly in the Crimea and the Caucasus, where they formed

Jewish enclaves surviving into modern times. One of the dynasties of Jewish princes ruled

in the 15th century under the tutelage of the Genovese Republic and later of the Crimean

Tartars. Another vestige of the Khazar nation are the "Mountain Jews" in the North

Eastern Caucasus (Koestler 1976). In the 16th century the total Jewish population of the

world amounted to about one million, suggesting that during the Middle Ages the majority

of Jews were Judeo-Khazars in origin (Polak 1951; Koestler 1976). The remarkable close

proximity of European Jews and populations residing on the opposite ends of ancient

Khazaria, such as Armenians, Georgians, Azerbaijani Jews, and Druze (Figures 3,

S2-3, 5), supports a common Near Eastern-Caucasus ancestry. These findings are not explained by

the Rhineland Hypothesis and are staggering due to the uneven demographic processes these

populations experienced in the past eight centuries.

20

The high genetic similarity between European Jews and Armenian compared to Georgians (Figures 5 and 6, Table 1) is particularly bewildering because Armenians and Georgians are very similar populations that share a similar genetic background (Schonberg et al. 2011) and long history of cultural relations (Payaslian 2007). We identified a small Middle Eastern ancestry in Armenians that does not exist in Georgians and is likely responsible to the high genetic similarity between Armenians and European Jews (Figure S6). Because the Khazars blocked the Arab approach to the Caucasus, we suspect that this ancestry was introduced by the Judeans arriving at a very early date to Armenia and were absorbed into the populations, whereas Georgian Jewry remained distinct (Shapira 2007).

| The suspicion, that Jewish ancestry was introduced to Armenians by the Judeans arriving at a very early date to Armenia and absorbed into the Armenian population, is strongly supported by the historical records. The Jewish history of Armenia numbers more than 2,500 years, and begins long before the emergence of the Armenia. In 700 BC Assyria seized control of Israel and Urartu ~ future Armenia, and deported Jews to these lands. The Jews of Samaria were deported to Armenia (Ref. Kevork Aslan). The Oral Torah (Midrash Lamentations Rabbah, ch. 1) explains that the Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar, after destruction of the First Temple in the 5th c. BC., drove some of the captive Jews to Armenia. In ancient times, all major cities and capitals of Armenia had Jewish settlements. Armenia now has so few Jews because during the early Christian times, almost all Jews professing Judaism were deported to Persia, and the Jewish converts to Christianity became Armenians. Armenians have a historical doze of the Middle Eastern ancestry, so no wonder genetic composition shows it. |

Similarly, the relatedness between European Jews and Druze reported here and in the literature (Behar et al. 2010) is explained by Druze (geographically) Turkish-Southern Caucasus origins. Druze migrated to Syria, Lebanon, and eventually to Palestine between the 11th and 13th centuries during the Crusades, a time when the Jewish population in Palestine was at minimum. The genetic similarity between European Jews and Druze therefore supports the Khazarian Hypothesis. We emphasize that testing the Middle Eastern origin of European Jews can only be done with indigenous Middle Eastern groups. Overall, the similarity between European Jews and Caucasus populations underscores the genetic continuity that exists among Eurasian Jewish and non-Jewish Caucasus populations.

This genetic continuity is not surprising. The Caucasus gene pool proliferated from

the Near Eastern pool due to an Upper Paleolithic (or Neolithic) migration and was shaped

by significant genetic drift, due to relative isolation in the extremely mountainous

landscape (Balanovsky et al. 2011; Pagani et al. 2011). Caucasus populations are

therefore expected to be genetically distinct from Southern European and Middle Eastern

populations (Figure 5), but share certain genetic similarity with Near Eastern

populations such as Turks, Iranians, and Druze. This similarity, particularly with the

Druze, should not be confused with a Semitic origin, which can be easily distinguished

from the non-Semitic origin (Figure 5). In all our analyses, Middle Eastern samples

clustered together or exhibited high similarity along a geographical gradient (Figure 3)

and were distinguished from Arabian Peninsula Arab samples on one hand and from Near

Eastern - Caucasus samples on the other hand.

21

Our study attempts to shed light on the Khazars and elucidate some of the most fascinating questions of their history. Although the Khazars’ conversion to Judaism is not in dispute, there are questions as to how widespread and established the new religion became (among non-Jewish converts). Despite the limited sample size of European Jews, they represent members from the major residential Jewish countries (i.e., Poland and Germany) and exhibit very similar trends. Our findings support a large-scale conversion scenario that influenced the majority of the population. Another intriguing question touches upon the origins of the Khazars, speculated to be Turk, Tartar, or Mongol (Brook 2006).

| An incorrectly formulated question can't have a correct answer. There are Turks and Turks,

Tatars and Tatars, and they have little in common. Although all four are culturally Türkic people,

their genetic histories are as close as that of the Indonesian Indians and Amerindians. The same

applies to Mongols, and in case of the Chingiz Khan as a prime Mongol example, his genetic origin

was Uigur, closer to Uzbeks than to Oirat Mongols. As saying goes, for a stupid question you'd get a

stupid answer. Historical sources defined Khazars as a small Türkic tribe, linguistically related to Bulgars, and the nature of the Bulgar language is well defined from the literary sources, inscriptions, and by M.Kashgari, a first philologist. No source identified Khazars with Suvars, although Khazars and Suvars lived in one polity and in close geographical proximity. |

As expected from their common origin, Caucasus populations exhibit high genetic similarity to Iranian and Turks with mild Asian ancestry (Figure 5, Figure S7). However, we found a weak patrilineal Turkic contribution compared to Caucasus and Eastern European contributions (Figure 7). Our findings thus support the identification of Turks as the Caucasus ancestors, but not necessarily the predominant ancestors. Given their geographical position, it is likely the Khazarian gene pool was also influenced by Eastern European populations that are not represented in our dataset.

Our results fit with evidence from a wide range of fields. Linguistic findings depict

Eastern European Jews as descended from a minority of Israelite-Palestinian Jewish

emigrates who intermarried with a larger heterogeneous population of converts to Judaism

from the Caucasus, the Balkans, and the Germano-Sorb lands (Wexler 1993). Yiddish, the

language of Central and Eastern European Jews, began as a Slavic language that was

re-lexified to High German at an early date (Wexler 1993). Our findings are also in

agreement with genetic, archeological, historical, linguistic, and anthropological

studies and reconcile contradicting genetic findings regarding European Jewish ancestry

(Polak 1951; Patai and Patai 1975; Wexler 1993; Brook 2006; Kopelman et al. 2009; Sand

2009). Finally, our findings confirm both oral narratives and the canonical Jewish

literature describing the Khazar’s conversion to Judaism and the Judeo- Khazarian

ancestry of European Jews (e.g., “Sefer ha-Ittim” by Rabbi Jehudah ben Barzillai [1100] ,

“Sefer ha-Kabbalah” by Abraham ben Daud [1161 CE], and “The Khazars” by Rabbi Jehudah

Halevi [1140 CE]) (Polak 1951; Koestler 1976).

22

We emphasize that we do not intend to cast doubt on Behar’s et al. (2010) and Atzmon et al.’s (2010) remarkable findings, but rather propose a comprehensive interpretation that explains the patterns they observed in whole genome data, those reported in the literature for uniparental data, and those observed here using both types of data. The point in these studies is that European Jews had a single Middle Eastern origin is incomplete as neither study tested the Khazarian Hypothesis, to the extent done here. Last, although disease studies were not conducted using Caucasus and Near Eastern populations to the same extent as with European Jews (Chakravarti 2011), many diseases found in European Jews are also found in their ancestral groups in Southern Europe, the Caucasus, and the Near East, attesting to their complex origins (Ostrer 2001).

Because our study is the first to directly contrast the Rhineland and Khazarian Hypotheses, a caution is warranted in interpreting some of our results due to small sample sizes and availability of surrogate populations. To test the Khazarian Hypothesis, we used a crude model for the Khazar’s population structure. Our admixture analysis (of Armenians and Georgians) suggests that certain ancestral elements in the Caucasus genetic pool were unique to the Khazars (i.e. Armenians and Georgians). Therefore, using few contemporary Caucasus populations as surrogates may capture only certain shades of the Khazarian genetic spectrum (or none at all, as in this case). Moreover, our conclusions regarding the fate of the Khazars are limited to European Jewish populations. Further studies may yield a more complex demographic model than the one tested here and illuminate the multi-ethnical population structure of the Khazars. Irrespective of these limitations, our results were robust across diverse types of analyses, and we hope that they will provide new perspectives for genetic, disease, medical, and anthropological studies.

Conclusions

We compared two genetic models for European Jewish ancestry depicting a mixed

Khazarian-European-Middle Eastern and sole Middle Eastern origins. Contemporary

populations were used as surrogate to the ancient Khazars and Judeans, and their

relatedness to European Jews was compared over a comprehensive set of genetic analyses.

Our findings support the Khazarian Hypothesis depicting a large Caucasus

(i.e. Armenian and Georgian) ancestry along

with Southern European, Middle Eastern, and Eastern European ancestries, in agreement

with recent studies and oral and written traditions. We conclude that the genome of

European Jews is a tapestry of ancient populations including Èóäîèçèðîâàí Khazars,

Greco-Romans and Mesopotamian Jews, and Judeans and that their population structure was formed in

the Caucasus and the banks of the Volga with roots stretching to Canaan and the banks of the Jordan.

23