2600-year-old Issyk Inscription.

Two lines of Saka inscription

that changed view on the history of the Türkic people

http://www.rizvanhuseynov.com/2012/12/2600.html

© Elshad Alili, Rizwan Huseynov 2012

| Issyk Inscription | ||

|

Elshad Alili 2600-year-old Issyk Inscription. Two lines of Saka inscription that changed view on the history of the Türkic people http://www.rizvanhuseynov.com/2012/12/2600.html © Elshad Alili, Rizwan Huseynov 2012 |

|

| Kyzlasov Alphabet Table | Amanjolov Alphabet Table | Amanjolov's Book Contents | |

|

Posting Introduction |

|||

The oldest inscription in Türkic alphabet, the

Issyk

Inscription, written on a flat silver drinking cup, was found in 1970 in a royal tomb located

within Balykchy (

Issyk),

a town in Kyrgyzstan near Lake Issyk, and was

dated by 5-th c. BC.

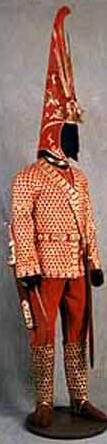

In the tomb was a body of a man dressed from head to toe in magnificent attire, the clothes, jacket,

pants, socks, and boots all had a total of 4,800 attached pieces of pure gold, greatest ever found

in a tomb except Pharaoh Tutankhamen. The top of the cone-shaped crown covering ears and neck carried

golden arrows emblem. A sword on the belt right side and a knife on the left were in sheaths.

Beautiful relief ornaments of animal art decorated shields, belt and front of the hat. Radiocarbon

tests determined the age of the finds as belonging to the fifth century BC. What was the world in

the 5-th century BC? We have archeological discoveries, where dating is almost always somewhat

speculative, and reconstructions of the ancient Greek maps, and the views of the Mesopotamian and

Chinese records. From the Mesopotamian, Chinese, and Greek texts, from the archeological discoveries

of the kurgans, from the written monuments, we get a glimpse of the nomadic nations of the Central

Asia in the 5-th c. BC. The various interpretations of the graphics and contents of the inscription

witness the paucity of the finds and the potential for the studies. The oldest inscription in Türkic alphabet, the

Issyk

Inscription, written on a flat silver drinking cup, was found in 1970 in a royal tomb located

within Balykchy (

Issyk),

a town in Kyrgyzstan near Lake Issyk, and was

dated by 5-th c. BC.

In the tomb was a body of a man dressed from head to toe in magnificent attire, the clothes, jacket,

pants, socks, and boots all had a total of 4,800 attached pieces of pure gold, greatest ever found

in a tomb except Pharaoh Tutankhamen. The top of the cone-shaped crown covering ears and neck carried

golden arrows emblem. A sword on the belt right side and a knife on the left were in sheaths.

Beautiful relief ornaments of animal art decorated shields, belt and front of the hat. Radiocarbon

tests determined the age of the finds as belonging to the fifth century BC. What was the world in

the 5-th century BC? We have archeological discoveries, where dating is almost always somewhat

speculative, and reconstructions of the ancient Greek maps, and the views of the Mesopotamian and

Chinese records. From the Mesopotamian, Chinese, and Greek texts, from the archeological discoveries

of the kurgans, from the written monuments, we get a glimpse of the nomadic nations of the Central

Asia in the 5-th c. BC. The various interpretations of the graphics and contents of the inscription

witness the paucity of the finds and the potential for the studies.The difficulties in interpreting the same spelling are not staggering, all researchers working with texts not broken into words encounter them, and the task is complicated by the absence of vowels even if the modern language is known and a scribe is perfect, the bsncfvwls can be parsed quite differently, in addition to the “absence of vowels”. On another hand, with the today's capabilities, we can generate a list of possible options in seconds, given that we know most of the consonants, and have appropriate dictionaries and algorithms. This is, of course, applicable to any text with partially known phonetics, like the phonetized record of the Hunnic phrase. We should welcome the fact that the discussion finally broke off from the closeted bounds to the public review on the Internet. And at last, the contents of the inscription finally fall within the known Türkic ethnological tradition of raising a leader to a throne, be he styled Shanyu or Khan or whatever: the chalice deposited with the Prince and its inscription appear to be the ceremonial cup he used to swear his oath of office during coronation, before being raised on a felt carpet and carried prescribed number of times around the Assembly of representatives. The departed was given his chalice, along with all other travel necessities, for the arduous travel to the other world. For a listing of other images, publications and attempts to read click here. Posting's notes and explanations, added to the original text and not noted specially, are shown in (blue italics) in parentheses and in blue boxes. |

|||

|

Ëèíêè |

|||

|

Elshad Alili 2600-year-old Issyk Inscription. Two lines of Saka inscription that changed view on the history of the Türkic people |

||

|

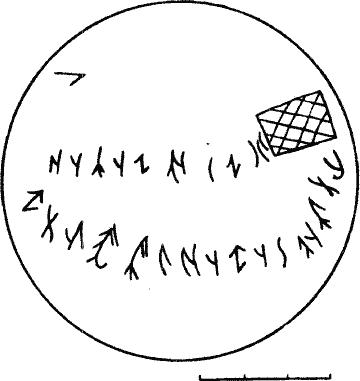

Saka “Golden Warrior”, Issyk kurgan In 1970, on the outskirts of the Issyk city, located fifty kilometers east of Almaty, the Kazakh archaeologists led by Kamal Akishev excavated one of the Saka royal burial kurgans. Kurgan with diameter 60 m and height 6 m had layered kurgan fill, beneath which was buried a young man. The deceased was later named “golden warrior”, because his helmet, caftan, trousers, and boots, were decorated with gold plates depicting snow leopards, horses, ibex, and argali, pictured in Scythian Animal Style. He also had a sword with a golden handle. The young man was also accompanied with other items, including ornamented dishes, platters, clay, bronze, and silver bowls. On the outside, that is on the convex side of a silver bowl was found an inscription in Türkic runiform symbols. The finds date from the 6th-5th cc. BC. The finds in the Issyk kurgan are unique in the number of objects and refined manufacturing technique of the decorations and utensils, and the content of the burial in historical terms is invaluable. The Issyk kurgan is one of the largest Scythian archaeological sites. The scientific and journalistic literature on Issyk kurgan, and its objects has plenty of information. In our case, we address only the reading of the runiform inscription on the silver cup, also known in the literature as “Akishev's bowl”. The inscription consists of two lines of twenty-five runiform symbols, most of which even visually are identified with the Old Türkic runiform characters. Next to the line is drawn a rectangular pictogram, divided into twenty-four compartments. The surface of the bowl is also has a separately etched runiform symbol separated from the two-line inscription. Silver “Akishev's bowl” with 2600-year-old runiform inscription There are several versions for reading the inscriptions in the Türkic language, with phonetic reconstructions of the characters slightly different one from another. And the translation, or interpretation of the text, in my opinion have inaccuracies. I present here the versions of the reading, and I think that of all the readings closest to the original is the version presented by the Kazakh Turkologist Altai Amanjolov. Lsater, I am presenting for a critical review my version of reading and translation. First of all, note that different interpretations, or rather different phonetic reproduction of text are caused by the absence of separation between the characters of the inscription. And in this case naturally may be different phonetic interpretations of the text. Moreover, we deal with a Türkic language of the 2500 years ago. And naturally, slightly different phonetic reproductions can produce different interpretations of the text. Given that the text is very short, which in such cases always impedes a 100% correct reading of the ancient text, such discrepancies should be treated with understanding. But again, the Türkic content of the text is clear, because most of the runiform characters have their counterparts in the Old Türkic runiform alphabet. To preface reviewing versions

of the reading, a few years ago, before deciphering the

text, I was only familiar with the versions and interpretations of Oljas Suleimenov and the Uzbek Turkologist Nasimhon Rakhmonov.

Other interpretations of the text I learned only later, from the server

http://turkicworld.org/turkic/turkicsite.htm. And I was particularly surprised by the same

interpretation of the absent in the Orkhon-Eninsei runiform symbology character

A. Amanjolov transcription: Translation: Muharrem Ergin transcription: Translation: The phonetic reproduction of the text by M. Ergin in places is closer to the A. Amànjolov's transcription, but his semantic interpretation raises many questions. Selahi Diker transcription: Translation: Again, there is some consistency with the original text, but the transcription is half not accurate, resulting in a liberal interpretation of the text. Above, I have cited three versions of the reading, which in my opinion more or less reflect the transcription of the text. Here are few more versions of reading: Firudin Agasi oglu Jalilov's version of the reading: It should be noted that Professor Firudin Jalilov reads both lines from left to right. He interprets the rectangular icon as “home, possession of the clan”. Transcription: Or 2. Koçu añısı ağ ebi Translation: Or Nasimhon Rahmonov's Translation: Oljas Suleimenov's proposed transcription: Translation: As I understand, the reading of the text is reproduced upside down, leading a completely different transcription. I have not followed this version of the reading, because I am convinced that the lines of the inscription are written from left to right. Kazim Mirshan's version of the transcription: Translation: Generally, the Kazym Mirshan's versions of the Türkic inscriptions' interpretations are usually contested even by the Turkologists. An extensive analysis of all above versions would take much time. Besides, that is not specifically necessary. Again, all of these versions the most accurate version was proposed by A. Amanjolov. The other authors correctly reproduce separate syllables, but generally because of the absence of separation between characters, the whole text is reproduced incorrectly. In that light, I offer for a critical review a version read and translated by me. First, I am giving the phonetic correspondences and transcriptions of the runiform characters on the cup. Then follow the transcription of the text and translation. I use estampage (squeeze) widely present on the web, including that in the Amanjolov's work. The runiform characters on the Akishev's cup largely correspond to the Orkhon-Eninsei characters, but at the same time the inscription is more syllabic than the Old Türkic texts. Anyhow, the time difference between them is a thousand years.

1. Character

2. Character

3. Character

4. Character

5. The fifth character in the sequence is a character

6. The sixth character of the first line corresponds to affricate NG (sağır nun), with the form

7. The seventh character

8. The eighth character

9. Finally, the last ninth grapheme of the first line corresponds to the Orkhon-Eninsei KK, which was usually used in conjunction with the vowel AA; Second line. Read from right to left. 1. Interpretation of the first character in the second row

2. The second character

3. The third and its identical twelfth

4. The fourth character

5. The fifth character

6. The sixth character

7. The seventh character S was discussed in paragraph 8 (

8. The eighth and sixteenth characters

9. ninth character S was covered above; 10. N The tenth character N

11. The eleventh character

12. The twelfth character eR was covered in the 3rd paragraph for the second line; 13. The thirteenth character eR/iR was covered in the 3rd paragraph for the second line. 14. The fourteenth character visually seems to be more like A/EE

covered in the 2nd paragraph for the first line. But in all likelihood this symbol reproduces a soft vowel Ü/Ö

15. The fifteenth character Z was covered in the 2nd paragraph for the second row; 16. The sixteenth character Ə (Ä) was covered in the 8th paragraph for the second row. Thus, has been formed the following scheme:

OĞA SeN ANg İÇ SaK Literal translation: Slightly extended translation: Literary interpretation of the meaning: |

||

|

Author's Notes |

||

The rectangular pictogram divided into 24 sections can symbolize the homeland with 24-clan

(tribe)

structure of the Türkic -Oguz El (Il), called OĞ/OG - people. Meaning of the words: oğ - clan, tribe, family hirarchy, tribal alliance, people (literally, arrow). In this sense the term is used in the large epitaph in honor of Kül-Tegin (political and military leader of the Second Türkic Kaganate, 685-731) cited in the Old Türkic Dictionary (OTD, p. 370). It is found in such Türkic tribal divisions as ON OK, ÜÇ OK, BOZ OK. In this case, oğ is used in dative case - oğa. This proto-Türkic (see box) stem forms the term OĞUZ. The verb uz is translated from the proto-Türkic as follow someone, join, conjoin (OTD 605, 620). I.e., literally OĞ-UZ is etymologically derived as united arrows;

sən - thou (OTD 45); ang - oath. Although in the Old Türkic period this word is better known as ant or and, Mahmud Kashgari noted the verb angar - to swear (Mahmoud al-Kashgari “Divanu lugat al-Turk”, Kazakhstan Oriental Research, Almaty, 2005, p. 238), with the root ang; (aŋɣar? OTD does not list it) iç - to drink (OTD 201). In the text the verb is used in imperative voice; sak - this is again lit. arrow. The word is synonymous with oğ/og/ok, and has with it a common semantic origin. It also carries such semantic meanings as tribe, man (a member of the tribal hierarchy), warrior, chief. A partial etymological analysis of this proto-Türkic term was given in the third, fourth and ninth parts of the work “Sakas of Sisakan and Aran”. Its ninth part also pointed to its Akkadian (24-23 cc BC) calque gamir/gimir. The Greek term Cimmerian is only an isogloss of the Akkadian form of the proto-Türkic term Sak. söz - word, speech (OTD 511). eren (erän) - wise, noble man, warrior (OTD 176). Eren in the text is used in a genitive form ereng; ögünç - praise, acclamation, extolling (including himself), glory (OTD 381); səs (söz) - voice, call, click; rumor, hearsay. In Türkic texts it is recorded only from the Middle Türkic period; ün - voice (OTD 625). And also rumor, hearsay, glory. ün tart - to sing dolefully. Ün is synonymous with səs. They are used in pairs as səs-üni in the genitive case. In the Old Türkic language is also recorded a verb sesin - desire, seek, intend (OTD 497). Possibly, in the text is not used the pair səs-üni, but sesini - desire, intention in the genitive; I would allow little probability to this option; er/ir - follow (OTD 175). eriş (erish) - lead to (OTD 180). erir - bring over, carry over. üzə - on the top, above (OTD 629). Is also used as an epithet of Tengri or the havens. The Türkic expression “drink up the oath” for some may sound strange It reality, to this day the verb swear is literally translated from Türkic (Azeri) language as “drink up the oath» - and iç (and ich). This is corroborated by the historical information. First, here is a testimony of Herodotus (Book IV-Melmopena, Ch. 70) (c. 484 - c. 425 BC): 70. All treaties of friendship, sanctified with oath, are thus among the Scythians. Wine mixed with the blood of the parties is poured into a large earthenware bowl, for that the skin is punctured with an awl or made a small incision with a knife. Then into the bowl sword are dipped arrows, ax and spear. After this ritual are recited long spells, and then the participants of the treaty, and the most distinguished of those present drink from the cup. (Reverse translation from Russian) And also an excerpt from a historical work of Ibn al-Faqih al-Hamadani (c. 950 AD) “Mukhtasar Kitab al-Buldan” (“Concise Book of Lands”), chapter on the Türks and some Türkic cities, and their peculiar traits: ...And when Türks want to take an oath from a man, they bring a copper idol, hold it, then prepare a wooden bowl, into which water is poured, and place it between the hands of the idol, and they then put into the bowl in a piece of gold and a handful of millet, bring women's trousers and place it under the bowl, and then say to the one swearing the vow: “If you'd break or violate your vow, or turn out flawed, let Allah turn you into a woman, to wear her trousers, and turn you over to what will tear you into smallest pieces, like this millet, and turn you yellow as this gold”. Then after the vow he drinks that water... The above citations exhaustively demonstrate that the Scythians of Herodotus were Türks. Only in the Türkic language “to swear an oath” is literally translated with “drink the oath”.

Thus, the silver “Akishev's cup” most likely was used for the ritual oath-taking, the brief text on the bowl states that directly. Firstly, it is obvious that most of the Saka tribes were Türkic-speaking, not Iranian-speaking, where Iranists are stubbornly mistaken, refusing to acknowledge the Türkic content of the Akishev bowl's inscription. Secondly it turns out that the Türkic runiform script was already in use in the period of the 5th-6th cc. BC This fact debunks the fabricated fable on the beginning of the Türkic script at the turn of the 5th-6th cc. AD. And certainly it is not associated with the Sogdian script, but has an indigenous origin. Generally, how can serious scientists hold that a meager hundred years after invention (or borrowing) of the script, it was organized into coherent and cohesive grammatical system and spread over a huge geographical territory (and many unconnected tribes and states). Those well acquainted with the Old Türkic runiform texts know that that alphabet in its content is very different from the others, and they should understand that this script, its grammar, and its stylistics passed a long developmental way before entrenching in the Orkhon-Enisei texts in the form known to us. |

||

|

References |

||

|

Əlisa Cəbrayıl oğlu Şükürov, Abbasqulu Məhərrəm oğlu Məhərrəmov:

“Qədim Türk Yazili Abidələrinin Dili”

(“Language of written Old Türkic monuments”), Bakı, 1976. Firudin Ağasıoğlu Cəlilov,“Issiq Yazisi”. A.A. Amanjolov. “Proto Runic-like inscription on a silver cup”. Mahmoud al-Kashgari “Divanu lugat al-Türki”, Kazakhstan Oriental Research, Almaty, 2005. “Old Türkic Dictionary”, USSR AofS, Leningrad, 1969. Herodotus “History” . Ibn al-Faqih al-Hamadani “Mukhtasar Kitab al-Buldan” (“Concise Book of Lands”). Elshad Alili “Sakas, Sisakan, and Aran”. |

||