The word “tamga” (aka belgü,

daɣ, taban, tamɣa, tamqa, taqba, and probably more; the form “tamga”

was borrowed into Russian) of a Turco-Mongol origin in the languages in

that group had several meanings: “brand”, “stamp”, “seal”.

During the Tatar-Mongol expansion of the 13th – 15th cc. the term spread in the conquered countries

of the Middle Asia, Eastern Europe, Middle East, Caucasus and S.Caucasus, where in addition to the

former meanings it acquired new meanings -

“document with the khan's seal” and “(monetary) tax”.

| The term Turco-Mongol is a political term; although the Mongol language of the Chingiz-khan was

much Turkified in the previous millennium after the rise of the Syanbi, it still was a distinctly

Mongol, and not a Türkic language, it is the language of the “Secret History”. In the 15th-17th cc.

that Turkified Mongol language disappeared, replaced by non-Turkified eastern Mongol language known

today as Mongol language. The Türkic word tamga was indeed in the lexicon of the Turkified

Mongol language of the Chingiz-khan times and court. The language was identical with the lingua

franca of the tri-partite Tatars, which were a collection of refugees who joined the Mongol Tatars

in the area of the Kerulen river.

However, the assertion of the “new meanings” is bogus: these functions predate the Chingiz-khan

times by a millennium and a half, officials were given badges carrying the tamga of the court, tamga

stamps certified payment of custom fee (custom tax), and payment of any other tax in any flavor and

form. What could be new is the use of tamgas in the Caucasus, but even that is doubtful since the

First Türkic Kaganate was collecting taxes in the Caucasus in the 6th c. |

The apparent popularity of the term in the Turko-Mongolian millieu from which it was borrowed

into the other languages (including Russian), still can not be considered as a proof of the Turko-Mongol

origin of the tamgas as fundamentally new marking system, versus for example the writing.

| This funny disclaimer is accurate, since nobody knows who invented customs stamps, but they were

used across Eurasia from pre-literate periods, as attested by the seals found on the transportation

vessels. |

Meanwhile, the specificity of tamgas' main use (as marks of clan or tribal affiliation),

undoubtedly class tamgas to the category of the most important historical sources. The scientific

study of the tamgas and tamga-like symbols has been ongoing for more than two centuries, and

although the achievements are indisputable, this topic and many related issues are still far from

being resolved.

Of the number of the topic's aspects - genetic, chronological, formal typological, functional,

etc. - below is considered only one - the functional aspect.

A survey of the works published on the topic revealed both a lack of proper and common

methodology for the studied symbolic systems (with a presence of quite acceptable local studies), and a

significant spread of opinions on the role and functions of the signs, including tamgas. The reason is obvious: the absence

(in most cases) of narrative descriptions for the “operation” of a

particular sign system, whereby (as well as due to the natural loss of the signs from the system's

“stock”) the conclusions of the research a priori looked like more or less justified hypothesis. It should be

obviously noted that in this paper the term “tamga” is used largely conditionally, that is, it does not

carry an “ethnocultural load”; hence the signs belonging to the non-Türkic and non-Mongol peoples may be

called tamgas. Likewise with the terms “tamga-type signs”, “heraldic

symbols”, etc.

| And pizza does not carry an “ethnocultural load” describing its eaters; a cultural borrowing is

a routine affair among humans, and not only humans. At the same time, a pizza sold at the Termine is

probably Italian, and the purpose of the pizza is about the same in Rome and in Saigon. Chinese, for

example, assembled a “tamga encyclopedia” to guide their purchases of different horses from

different Türkic tribes (Ref. Yu. Zuev, 1960, Tamgas

of vassal princedoms, Tanghuyao).

This qualification probably attempts to create a bridgehead

for forthcoming disclaimers on sensitive ethno-cultural matters. |

The following is a synopsis of the main signage systems used by sedentary and nomadic

populations of the Eurasian steppe and forest-steppe belt in the last 2.5 millennia.

| We pass the forest zone, where apparently were no nomads, no horse husbandry, and no tamgas. |

Sufficiently well studied and documented are the tamgas of the Kazakh tribes of the Senior, Middle and Junior

Juzes (Kudayberdy-uly Sh. 1990; Vostrov V.V., Muhanov M.S., 1968). The formation of the Kazakh tamga system

belongs to the Middle Ages era, it also exists today. The Kazakh tamgas are geometric, structurally

simple, and their number is relatively small, roughly corresponding to the number of clans (tribes). They are collective

signs: all members of the same clan have one tamga.

| The faulty dating is predicated by the presumed date of the Kazakh nation: no Kazakhs, no

tamgas. The assumption and the dating are false because the Juzes (Russian knock-off Souz,

like in the Souz of Soviet Socialist Republics, the former USSR, the so- is a Slavic prefix

“with”, and -uz is the Kazakh juz “union”) coagulated at very different times,

and of very different tribes. The oldest is the Senior Juz, its base are tribes of Usuns, known from

6th c. BC, and Kangars, known from 23rd c. BC. The Usun - Ashina (Oshin) tamga represented a raven.

Usun genesis legend included Raven as a totem. The Usun Juz (confederation, union) formed in 161 BC,

and by 100 BC it was a coherent political entity with its own foreign relations. The Usuns, called

Uisyn in Kazakh, constitute a nucleus of the Senior Juz, and they are documented, with their tamga,

from 6th c. BC.

Next formed the Middle Juz, in the early Middle Age, and then the Junior Juz, in

the late Middle Age.

The kind of nonsense propagated in the Soviet times served to divide people into superiors and

inferiors, to justify imperial ambitions of the superiors of the superiors and to divide peoples for

better control and ethnic engineering undistinguishable from racism.

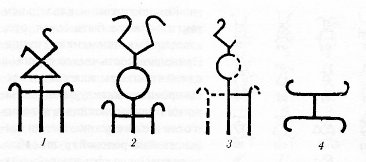

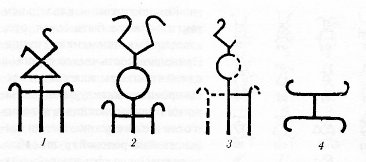

Omitted in the discourse is that each clan and down to individuals have their own modification of

the tribal tamga, by attaching simple and easily recognizable markings to the base image. The prime

utility of that is to distinguish cattle belonging to the relatives: father and son, brothers, etc.

Thus, with time, the complexity of the image grows, it is readily apparent, for example, in the tamgas

of the Kushan royals.

The continuity and discontinuity is clearly visible, and so is the erroneous

attribution: the first two tamgas are those of Kanishka, third and fourth are of his blood relatives

and possibly co-rulers or autonomous rulers, and the last is of somebody's else. |

The signs of various shapes close to tamgas and obviously heterogeneous in nature were known in Kazakhstan and in the

1st

millennium BC, they were used, in particular, on the ceramic vessels for different purposes before

or after firing (Baipakov K.M., Podushkin A.N., 1989, p. 142-151), they are also known from later

times (Smagulov E.A., 1979).

| The artisan stamp essentially plays the same role as the tamga cattle brands: to distinguish one

maker from another; obviously the artisans were sedentary and worked for the market; they did not

need to identify the tribal affiliation; quite the opposite, on the open market their tribal

affiliation could destroy their trademark. |

The

Nogais, Karakalpaks, Kirghizes, Altaians used tamgas as tribal markers (Poznan BC, 1991).

Mongolian tamgas probably chronologically precede Kazakh, they extend to this day. Among them, in

addition to the simple shapes and similar tamgas in other regions of the Middle Asia, Kazakhstan and the

Black Sea area, are more “decorative” forms, they were definitely used as clan's, and perhaps as a

family signs (Vainberg B.I, Novgorodova E.A., 1976; Baski I., 1997, p. 151, 152).

| It is hardly possible to project the term Mongol beyond the 13th c. Before that, and largely

after that, the Türkic or Mongolic content of the term “Mongol” is mostly speculative. Before

encountering the Scythian-type horse nomads called Juns (Rongs) and Jous (Zhou) by the Chinese, the

east-northern aboriginal tribes south and east of the modern Mongolia (future Mongols and Tunguses

as two main stems), were sedentary hunters with subsistent sedentary-type agriculture that included

pigs; these tribes were marked by a predominance of Y-DNA Hg C and mt-DNA Hg C, whereas the

Scythian-type horse nomads were marked by the predominance of Y-DNA Hg R (R, R1, R1a, R1b). The

sedentary aborigines did not have any use for tamga branding of their cattle, they did not have

roaming cattle. The Mongolic tribes were incorporated into the Hun empire (ca 200 BC) or hid in the

mountains and taiga to become known as Uhuan and later Syanbi Mongols. Only the Mongol tribes

associated with the Hun empire joined the horse nomadic economy and started using the Türkic tamga

branding. In ca 150 AD a part of nomadic Mongol tribes called Syanbi took over command of the

numerically far surpassing 500,000 Huns, creating a first Mongolic-led nomadic confederation. Their

descendents eventually moved from the Central Asia to the Middle Asia, adding their mix to the local

Kazakh tribes; that movement started with Karakhanids and Karakhtais ca. 1200, continued in the

Chingizid time, and is impressed in the anthropological, ethnical, and tamga contributions. Those

western Mongols developed a Chagatai Türkic lingua franca, hence culturally they already were Türkic

tribes, and they yet did not carry a Mongol label until the later Mogul times. |

A strong

tradition of using tamgas as family and tribal symbols is recorded among Chuvashes and Bashkirs, and a

significant part of their tamgas has a typological similarity with tamgas of the Türkic peoples (Kuzeev R.G., 1974; Ahmerov R.B., 1994).

| According to the linguistic assertions, Chuvashes (Ogurs or Proto-Ogurs) separated from the bulk

of the modern Türkic peoples in the 1st – 2nd mill. BC, hence they are a living testimony that

the tamgas, common to the Chuvashes and the bulk of the modern Türkic peoples dates to the 1st

– 2nd mill. BC (unless other alternatives can be substantiated). The modern Bashkirs are an assembly of many individual tribes with their individual history. For

example, the Abdaly (Abzeli of Bashkortstan, Ephthalites) migrated with their tamgas and genetic

make-up, Kipchaks migrated with their tamgas and genetic make-up, etc. Their tamgas are

typologically identical with the Abdaly and Kipchaks living in other areas, like Russia, Turkey,

Caucasus, etc., so as soon as scholars of history dispose of the modern politico-administrative

division, the “Bashkirs” tamga would disappear, and instead would become visible the Bashkir proper,

Abdaly, Kipchak, etc. tamgas. Projecting the newly established politico-administrative

division (ca 1920s) onto the phenomenon extending to the 1st – 2nd mill. BC debases the whole

idea of science. |

The tamgas of Tatars were widely used, especially in their places - in the Crimea (from 13th

c.), in Dobruja, etc., the clan and familyl tamgas were often depicted on vertically installed

headstones (Akchokrakly O., 1927; Baski I., 1997), and the khans' tamgas were minted on coins (Lebedev

V.P., 1990).

| Here the term “Tatars”, like the above “Bashkirs”, has nothing to do with ethnicity or the

subject of the discourse, this “Tatars” is synonymous with the “Türks” and another moniker “Mongolo-Tatars”.

Generally, it denotes specific “them”, “not us”, and carries as much ethnic weight, although it is

predominantly and deceptively used in the ethnic context, like in the above sentence. On a taxonomic

level, the term is equivalent to the terms “Nigger”, “Gringo”, or “Paki”, but since it is

ensconced in the official Russian lingo, its slurred nature is not felt by its users.

In adjectival form with a determinant the term is officially and routinely used towards numerous

unrelated people: Baraba Tatars, Siberian Tatars, Dobruja Tatars, etc., but only towards the Itil

area Türks it is used without a determinant. Most of the switch-over from the native ethnonym to the

Russian monikers occurred in the 20th c., when the monikers were elevated from the official and folk

lingo to a state-defined nomenclature used in mandatory passportization and censuses. Like with

cows, every cow may deem itself a princess, but it is up to a farmer to grade them “slaughter house”

or “milk”. The tamgas on the gravestone mark the family, and every member of the family knew who

is buried under each tombstone. An elaborate tradition of recurring commemorative rituals for each

deceased kept the memory alive and educated minors. In addition, practically every deceased had a

sequence of names known to the outsiders during the lifetime, and a private name known within the

immediate family but as a rule not to the outsiders; that makes mentioning the names pointless and

confusing. The rulers were buried under their official title being the name, and with a personal

tamga. |

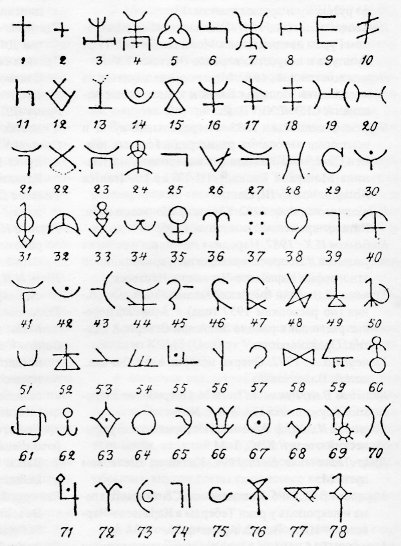

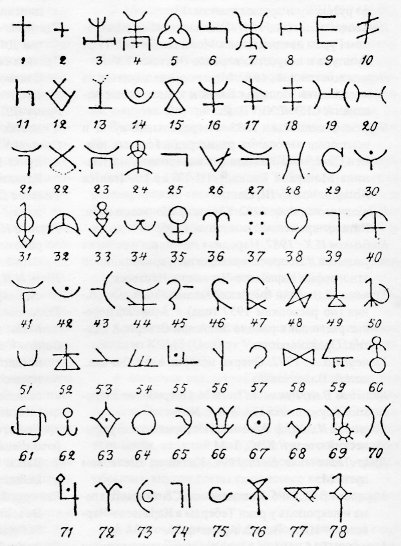

Tamgas were also known to the early Türks (including Oguz), next to the borders of China, not later

than 7th c. AD, as tribal symbols they were widely used for branding horses (Yu.A.Zuev, 1960). The early

Türks' tamgas largely differ from the rune “letters” of the runiform alphabets synchronous

with them (Kyzlasov I.L., 1994), although a few among them are tamgas identical with the runes (Fig. 1).

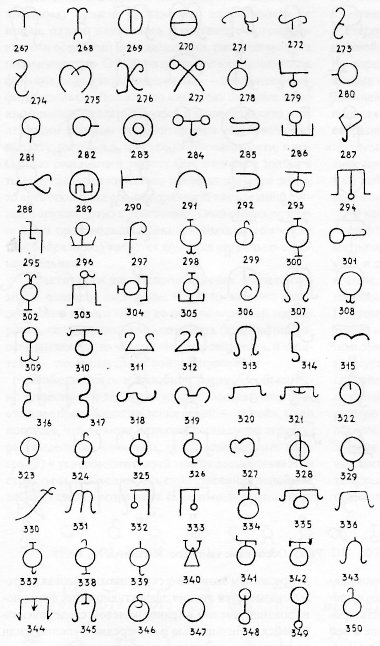

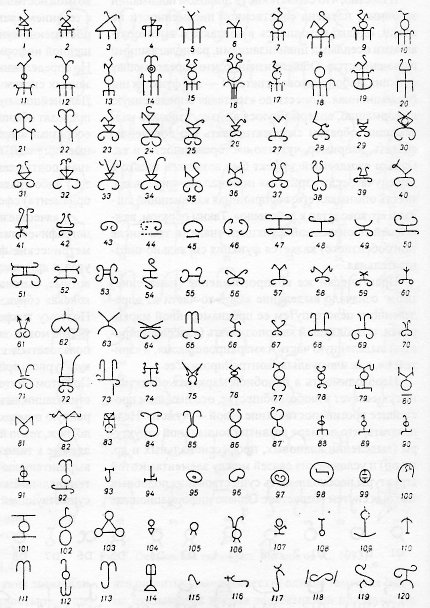

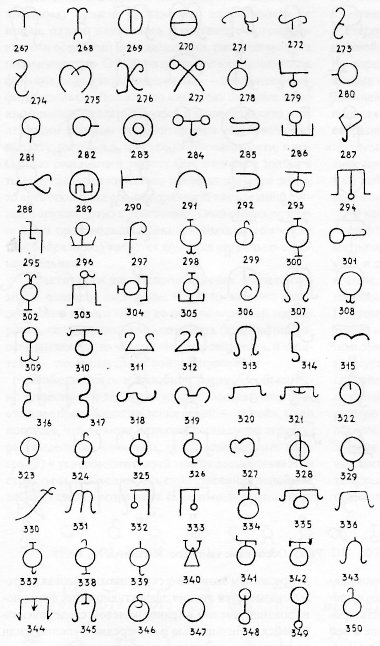

A developed system of family and kinship (and perhaps personal) tamgas had Hungarians (Fig. 2) and

the Bulgarians during their migration to the west and at a later time (Baski, Imre, 1997, p.153).

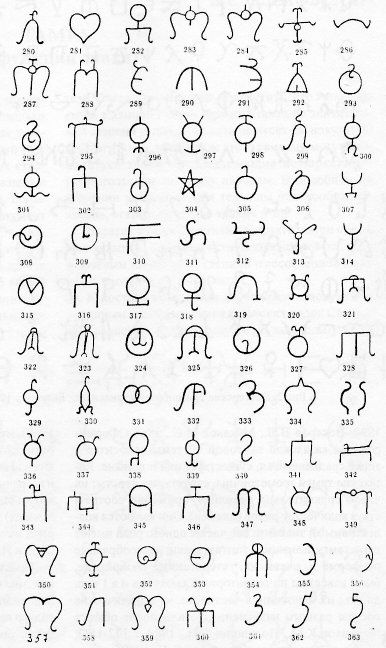

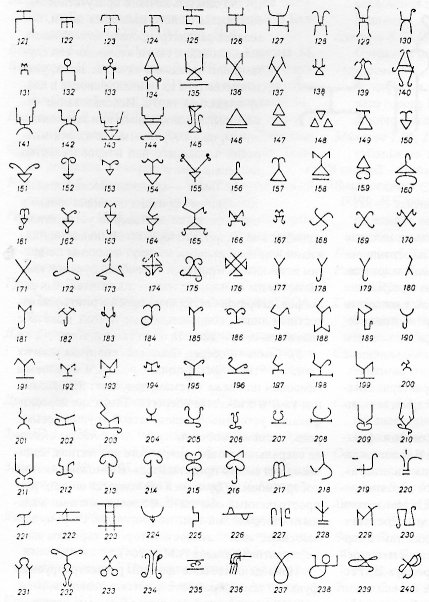

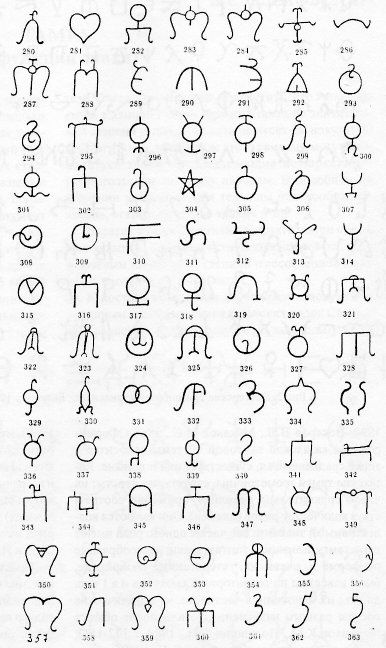

Ðèñ. 1. Äðåâíåòþðñêèå òàìãè

(ïî Ý. Òðèÿðñêîìó, èç Áàñêè È., 1997) |

Ðèñ. 2. Âåíãåðñêèå òàìãîîáðàçíûå çíàêè (ïî: Áàñêè È., 1997) |

Fig.1. Old Turkic tamgas

(by E. Tryarski, after Baski I., 1997) |

Fig. 2. Hungarian tamga-like symbols (after Baski I., 1997) |

|

|

The Mansi of Northwest Siberia used various family or personal symbols - katposes - almost

to modernity (Alekhin

K.A., 1997), not only as symbols of ownership, but also as graffiti marking the presence of the katpos' owner

in the others' hunting territory.

Ðèñ. 3. Êàáàðäèíñêèå òàìãè

(ïî: ßõòàíèãîâ

Õ., 1993) |

Ðèñ. 4. Àáàçèíñêèå òàìãè (ïî: ßõòàíèãîâ

Õ., 1993) |

Fig. 3. Kabardin tamgas

(after Yahtanigov H.,

1993) |

Fig. 4. Abazin tamgas (after Jahtanigov H.,

1993) |

|

|

From the Middle Ages, tamgas and tamga-like signs are also very typical for a number of Caucasian peoples: Kabardins (

Fig. 3), Nakhs (Ru. Chechens), Ingushes, Abasins (Fig. 4), Balkars, Karachais,

Adygs, Circassians, Abkhazians, and Ossetians (Fig. 5) and others; practically, they

are used presently (Yahtanigov Kh., 1993). It can be deemed established that in the Caucasus, tamgas

are used primarily as a

clan and family symbols, but there is a possibility that some of them served as personal

symbols, as a signature.

Ðèñ. 5. Îñåòèíñêèå òàìãè

(ïî: ßõòàíèãîâ

Õ., 1993) |

Ðèñ. 6. Òàìãîîáðàçíûå çíàêè íà

àõåìåíèäñêèõ ïå÷àòÿõ

(ïî: Boardman J., 1998) |

Fig. 5. Ossetian tamgas

(after Jahtanigov H.,

1993) |

Fig. 6. Tamga-like symbols on Ahemenid seals

(after

Boardman J., 1998) |

|

|

No doubts raises the fact that the Alans had a tamga system (Minayeva T.M., 1971, photo 17, Fig.

22), apparently a result of the development of the chronologically previous system of the “Sarmatian symbols”.

| In the Vs.Miller/V.Abaev hoax, Alans serve as a stepping stone in the logical chain Ossetes

> Ases > Alans > Sarmatians > Scythians. No link in this chain is proven, and every link is

disproven. However, the scheme was taken into Soviet political armory, and still lingers on. The

Türkic Masguts were nicknamed Alans ~ “Flatlanders” by their highland neighbors, Masguts were a part

of the Caucasian Huns, who are positively identified with the Türkic people, the Caucasian Masguts

were a splinter of the Türkic Dahae ~ Tokhar confederation of the Saka tribes that sustained assault

by Cyrus that cost him a head at the hands of the Masgut queen Tamar.

Naturally, all horse nomadic tribes, including Alans/Masguts/Massagets had a tamga marking

system, otherwise they would not have been able to keep track of their flocks in the pastures,

during military campaigns, and at the marketplace. And naturally, the horse nomadic Sarmats had a

tamga marking system. We do know that dynastic lines extended at least from the Sarmatian times, for

example the line of Siavushids lasted for one and a half millennium, plenty of time to leave their

tamgas behind. |

In the Rus, in the 10th-13th cc. had notable distribution the “Rurik signs”, the tamga-like signs

in the form of bident or trident. They were marking weapons and tools, works of art, ceramics,

and architectural structures. Especially often these signs occur on the lead trade seals and

document stamps, pointing to their “legal significance”. In recent years, the study of the Rurik

signs allowed to trace the

process of transforming a clan sign into a personal sign, and identify patterns reflecting

the process in the typological features of the signs (Beletsky S.V., 1999). Some

resemblance with the Rurik signs have the synchronous and later heraldic insignia of Poland and

Lithuania, which are often based on bident or trident ((Beletsky S.V., 1999, pp. 320, 321). The majority of

their forms resemble the Rurik signs and Sarmatian and early Türkic signs. This

similarity, considering the chronological position of these groups of signs, indicates the presence

at the

certain part of the Slavic population still in the pre-Mongol times of a developed system of family and

personal signs. Rather obviously, the tamga-like signs were primarily used by the social elite.

| Unfortunately, this is another example of patriotic galimatia that equates the non-Slavic

ruling elite with the Slavs, and then equates the ethnology of the ruling elite with the ethnology

of the Slavic peasantry. Likewise, the confederation Rus is equated with much later Russia. The last

ruling Rurikid Ivan the Terrible died in 1584, and with the change in the dynastic line, the Dulo

tamga was abandoned and suppressed. Instead of being proud that the Rurikids descended from the Hunnic dynastic

line Dulo, which produced a continuum of European dynastic lines, including the Rus,

Poland, two (or three) Bulgarias, and Hungary, and the Kushans in the Hindustan, the patriotic

fantasy offers a hodge-podge of questionable inferences and illogical interpolations. To avoid

using the Türkic term tamga, the quasi-scientific politicians routinely come up with

substitutes, in this case a clumsy non-statement “sign” instead of the nowadays Russian word

tamga. Tamgas were the most precious possession of a tribe, clan, or individual, they were

heirloom and heritage, and they carried a great legal significance. Accordingly, an unjustified use

of tamga, by a person ineligible for tamgas, or use of another person tamga was classed as a most

grave crime, and persecuted accordingly. These conventions are still observed in the societies which

practice the tamga traditions. |

A slightly different character, but somewhat similar graphics have the pottery markings at the

bottom of the vessels made on a potter's wheel. Such signs were widely used throughout the

territories of the Slavic

peoples from 9th to 14th cc. (Gupalo V.D., 1985). However, they are not tamgas, in spite of a certain resemblance, primarily due to their limited functional “field”, significantly

limited functional diversity (universality) of the real tamgas. A separate group of markings are the old

Rus “bort marks”, the signs that marked “bort trees”, the bee “hives” from which was extracted

honey. These markings are varied, they identified the the owner of the tree, being a legal proof of ownership. The

time of appearance of the bort marks is unclear (but not later than

the 11th cc.), they were used at least up to the 17th c. (Anpilogov G.N., 1964).

| The artisan trademarks in the “Slavic lands” indicate a rise of artisanship and sustained trade

relations. The “Slavic lands” were populated by numerous non-Slavic people, so the ethnic

attribution is quite dubious. Before appearing in the “Slavic lands”, the potter wheel and artisan

trademarks were used elsewhere for millenniums, and till the stratification of the Slavic societies

were probably imports. Bort and bortnik are Türkic terms for wild honey husbandry, they appear in

the ethnonym Burtas, the Türkic name for Mordva, who apparently were known for producing honey and

alcoholic fermented honey drink. The allophones of the words bort and bortnik are

kbown in Czech and Polish, pointing to forest belt specialization. In Türkic societies, honey was in

great demand not only as a sweetener and drink, but also as a preservative in the funeral rituals,

when a deceased ruler was taken over his domains in a casket filled with honey, a trip which could

last for many summer months. The tamga of the ownership in the forest belt was a knock-off of the

cattle branding, and possibly appeared first along the meridional pasturing routs. |

A distinct kind of markings with typological and often with full graphical similarity with tamgas

are the architectural and construction signs, marking bricks (before or after firing), stone blocks,

and other building materials. A distinction of such markings is the expressed absence of a desire by

their creators to their advertizing, “presentation” to the audience. Apparently, this group of signs

was used as technical markings primarily for the builders, it contained information of the maker

(master), customer, or “superintendent” of the construction. Possibly, they are a kind of

“acknowledgement”, informing viewers or customers of the fulfillers of the order and certifying

quality. Very expressive examples of such signs were found on the monuments of the ancient Rus

architecture of the pre-Mongol era (Rappoport P.A., 1985), on the bricks and

ceramics of the Khazar cities (Flerov V.E., 1997), on the early Bulgar fortress walls (in

particular, Pliska) and other structures of the 7th-10th cc. (Makarova T.N., Pletneva S.I., 1984).

Thus, the bort signs, the ceramic and “brick” symbols can be seen as a special sign systems, much similar to tamga systems in form,

purpose, and structure. Quite possible and

probable is the connection (including genetic) of these systems with fairly developed existing

parallel tamga systems in the same ethno-cultural milieu.

Complex tamga-like signs were also known in the Sasanid Iran (224

– 651) (Lukonin V.G., 1961).

The Sasanid Persia was a successor of the Parthian Empire, established by the horse nomad tribe

Pardy, an offshoot of the Tokhar (Dahae) nomadic confederation. The Sasanid state inherited all

nomadic traditions of the Parthians, and naturally understanding and use of tamga was a part of that

inheritance.

Tamga in front of the horse, Indo-Parthian coin,

Gondopharan Tamga

Reference to the Sasanid Iran without mentioning the Parthian Empire reflects the

institutional blindness on the part of the patriotic Russian scientology, which goes to great lengths to

emphasize linguistically Iranic component of the Asian history while trying to minimize, debase, or skip

altogether the

non-Iranic counterparts.

|

The fact of using a developed system of signs for marking bricks in the Middle Asia and Near East

in the earlier, Hellenistic

period, is noteworthy (Kruglikova I.T., 1986, p. 59, 61, 88, 94). So, the signs, some of which have an undoubted resemblance to later

“classical” tamgas

of the nomadic peoples of Middle Asia and Kazakhstan, were found in Khorezm in adobe buildings, dating

no later than from the 4th c. BC (Gertman A.N., 1998). However, earlier and unmistakable evidence

of the use of signs, “artisan markings” were found in Asia Minor, particularly on some Persepolis

buildings (Kleiss W., 1980). In that region, including Anatolia, was found indisputable evidence

for the existence of a developed system of the tamga-like signage. Signs of various shapes, some identical

with the tamgas of the later time, in the Achaemenid Iran, that is no later than 6th-5th cc. BC, were

on the signet rings (Boardman J., 1998), apparently in lieu of a personal signature of

the holder (Fig. 6).

| It may seem incredible, but 15 hundred years later, at about 1000 AD, most European rulers were

illiterate, and could not sign their signature. Each had its place in the society, cows produced

milk, scribes wrote and read, and rulers ruled. The name-seals may predate any tamgas in the world,

and they are still around in daily usage. The concept of wet signature is a recent concept. |

Somewhat later the tamga-like signs became widespread among the Sarmatian nomads that

in the end of the 1st millennium BC – 1st half of the 1st millennium AD (ca

2nd c. BC – 500 AD) united numerous etno-tribal groups (mainly linguistically Indo-Iranian) in

the zone of the Eurasian steppe belt and adjacent regions. In the North Caucasus, Crimea, Northern Black Sea,

and Middle Asia were recorded hundreds of typologically different and varied tamga-like symbols on

the

weapons, harnesses, jewelry, pottery, cult objects, architectural details, anthropomorphic and

zoomorphic sculptures, etc. Some signs in the territories, distant from each other by hundreds and thousands of kilometers,

are identical, which can be explained by nomadic

economy and migrations of the Sarmatian tribes (Solomonik E.I., 1959; Drachuk B.C., 1975). In some cases, Sarmatian

tamgas form clusters (sometimes called “encyclopedias”) of several dozens or even hundreds

of characters (Yatsenko S.A., 1992, 1998 ; Olkhovsky B.C., Yatsenko S.A., 2000).

| From a scientific standpoint, the assertion on “mainly

linguistically Indo-Iranian” is a hoax, perpetrated by Vs. Miller and V.Abaev, who fabricated facts

on the ground and manipulated a few primitive schemes to substantiate the Scytho-Iranian (sic! not

Indian!) paradigm. That patriotic idea was readily and largely uncritically accepted by the

Indo-European science, unwittingly making it a pseudo-science. The author, V.S. Olkhovsky,

gracefully inserts minor amendments, making it “mainly

linguistically” instead of simple “linguistically”, and “Indo-Iranian”

instead of simple “Iranian”, but that does not change much. Indo-Iranians

and Iranians equally did not belong to the Kurgan Culture, did not have a horse husbandry culture,

did not have a tamga culture, did not have lexicon for mounted riding, did not have lactose

tolerance needed for folks living of milk and meat, used mercenary cavalry in their armies, did not

live in horse-drawn mobile homes, did not do cranial deformation, and so on without an end. The laundry list of “did nots” is in

excess of 50 items, and is growing daily. The author, V.S. Olkhovsky, must be given a credit for

mentioning the Türkic people at all, for many years in his country that was a taboo. Still, in the humanities, it is possible

to assert an impossible as long as the audience favors your point. The last nail was driven by the

genetics that did not find any Iranian alleles in the bones, and instead suggested local folks like

Altaians, dancing around the Türkic axel like mules around a grain mill shaft. Nowadays, the

Scytho-Iranian paradigm has shrunk from an axiom to a purely linguistic theory, and is held together

by an endless chain of references where one non-linguist cites in a footnote other two non-linguists

as a proof. The suggested timing is alike off the calf. The Sarmatian chronology is well

established in archeological, anthropological, and biological aspects. And beyond that, there are no

reasons to postulate that the Kurgan waves that flooded Central and Western Europe in 4400-4300 BC,

3500 BC, and soon after 3000 BC were not some kind of Sarmatian ancestors. The Huns and Alans were

some type of Sarmatians. The Sarmatians were taxonomically Uralic-type, and Uralics populated the

Aral area to the end of the 3rd mill. BC, when at the turn of the 2nd Mill. BC aridization forced

them to migrate westward, northward, and eastward. They came back at the turn of the 1st mill. BC as

mounted Kurgan Timber-Gravers, repopulating the river valleys and wetlands. At the same time, at the

turn of the 2nd Mill. BC, the ancestors of the Indo-Iranians started their migration from the

N.Pontic southeast, in the opposite direction, moving into the Indian subcontinent and Iranian

Plateau, and arriving ca 1,500 BC. It is positively known that at their arrival in the south-central

Asia, the Indo-Iranians did not have a tamga culture, they did not preserve it, and did not pass it

to their descendents. Their tamgas, if any, are a cultural borrowing.

It should be noted that the isotope dating still is not done by the Russian archeologists.

Although much of the later tamgas can be dated by various indirect methods, the earlier suspects are

“dated” by consensus, “he said, she said”. The age of the oldest artifacts has not been established

yet. |

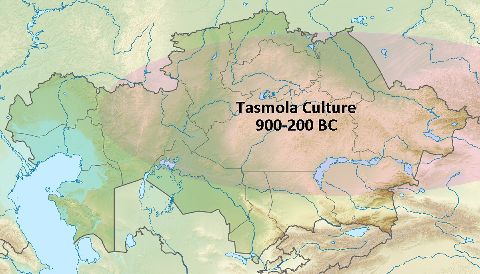

Around the same time (ca

2nd c. BC – 500 AD), tamgas appear on the coins of the Middle and Near Asian states ruled by the “nomadic”

dynasties, above all these are the Khorezm, Kushan, and Indo-Parthian coins (Weinberg B.I., 1977).

The connection of such tamgas with the “common Sarmatian” tamga world is quite obvious.

Thus, identified to date in the Near East reliable evidence of sustainable use tamga-like symbols date

from the middle of the 1st millennium BC. Sometimes, less reliable testimony of the simple symbols

engraved on bone, rarely on bronze arrowheads of the Scythian time (900 –

200 BC), attests to the Central Asian origin of the tamgas (Kocheev

V.A., 1994). Still more problematic are the results of the search for “proto-tamgas” in the monuments of the Bronze Age

(i.e. steppe Bronze Age, ca 3300-1200 BC). So,

although the hand-made vessels of the Timber Grave cultural community had numerous different signs

and pictograms (Zakharova E., 1998), it is hardly right to see them as letters or characters that serve

as tamgas. Equally incredible is “to find” the prototypes of the Adyge and Crimean Tatar tamgas on

the Greek pottery

of the 6th -5th cc. BC (Yahtanigov Kh., 1993, pp. 38, 43). Attempts to pronounce the Caucasus

petroglyph symbols as tamgas

and “a kind of script” of the 5th – 1st mill. BC, and at the same time state their Türkic

identity and presence there in the 10th -8th mill. BC of the Türkic titulature (Jafarov J.I.,

1993), have nothing to do with the science.

| Both opinions on the Caucasus petroglyphs appear to be unrelated to science. With the absence of

chemical analysis and graphological research, they are on the level of “he said, she said”. |

The reviewed groups of symbols that existed in the early Iron Age and Middle Ages Eurasia allow to conclude that:

- conversion of graphic symbols into a system suggests ordering, i.e. a presence of certain

rules in formation and functioning of the symbols;

- emergence of symbolic systems requires certain social conditions, in particular, existence of potential “carriers” and “consumers”

of the signs;

- the genesis of the symbolic systems is associated not so much with the nomadic, but with

the sedentary world, as a rule more developed economically; however, the tamga system becomes very effective

functioning specifically in the (early) nomadic environment, distinct by mobility and often by complete

or almost complete absence of written language;

- the system of tamga-like symbols can coexist with other information systems - pictography,

literacy, etc.;

- the functions of the tamga-like signs in different sign systems and ethno-cultural environments were

different;

- the presence of identical form signs in different sign systems does not constitute an absolute proof of their real

connection; fully permitted is their heterogeneity.

| This hodge-podge “conclusions” appear more to be premises than conclusions. The tamga cultural

tradition can be called system only conditionally, and then only with a clear definition of what the

term “system” means. Neither quantity of components, nor their variety or uniformity do not make a

collection a system. The difference between tradition, a specific practice of long standing, and

organized structure for arranging, operating, or classifying called “system” is great, and even

codifying a tradition does not make it a system without extended functioning of the tradition under

new conditions. It is one thing to describe and analyze a tradition; is is completely different

thing to describe a system. The first does not need any premises; the second assumes an objective

the system is supposed to meet, even if the objective is not defined beforehand. Thus, “conversion

of graphic symbols into a system” is a non-statement.

Tamga is a means of communication, and any communication involves two sides, a communicator and a

comunicatee. This is a nature of communication, be it codified (e.g. alphabet) or spurious (e.g.

croaking of frogs). The statement on “social conditions” is a non-statement statement.

Nomadic vs. sedentary world would have been true if the pots had feet and mingled en mass in the

free ranges. Then the pot makers would have to mark them to bring the right pot home. The sedentary

peasants do mark their cows, so that the village shepherd can see from afar and guide the right cows

to the right homes. The shepherd's dogs also learn that science, and know what to do, when, where,

and and to whom. They also brand them against poachers, like did the ancient nomads. Nowadays the

suitcases tend to walk away with strangers from the airports, so the passengers mark them for better

visibility and distinction. It is done whether the passenger is literate or the dog is illiterate,

the distinction should be clear to either one. On the literacy level of sedentary society, we have

an authoritative source: V.Lenin complained that Russian illiteracy was 80%, while the Tatar

literacy was nearly 100%. In the 1900s, Russia belonged to the “developed” and “literate” sedentary

and agricultural world, and Tatars belonged to the “undeveloped” and “illiterate” nomadic world.

As a side note, the author, V.S. Olkhovsky, repeats a pretty much racist mantra spread in the

sedentary worlds eons ago. If that mantra was true, the sedentary peasant owners would not have to

built Chinese Walls and organize hunting parties to hunt down their run-away property. The nomadic

world was always attractive to the bonded peasantry, it did not have a tradition of hard labor, nor

of a forced labor, and that trait was numerously noted by the chroniclers. The mantra was especially

popular among the peasant owners, since they did not have to labor themselves. Another example is

the Slavic part of the Cossacks, who chose the free life of nomadic mercenaries to the enslaved

tillage. As to the self-aggrandizing “more developed economically”, no peasant at any time in

history could even dream of the income routine in the nomadic economy: an average nomadic family had

30 horses, and produced 6 horses for the market; at Byzantine prices, that amounted to 6 lb of gold

per family if they sell all their merchandise at Byzantine market prices. At local markets, the

income was much less, 5 kg of silver annually per family. A single horse during imperial times was

sold for 20, 60, up to a 100 rubles. Twelve such horsed would equal a salary of a Russian

Prince. And the nomadic Nogais were selling 120,000 horses annually, at any market they wanted. A

Russian peasant, in contrast, could spend all his life and never see a single silver denga.

So much for the illiterate and poor “developed” world.(Jacques Margeret, The Russian Empire

and Grand Duchy of Muscovy, University of Pittsburgh, 1983, pp. 47-50)>

The last item, that a symbol specifically identifying a clan (tribe) or a member of a clan can

accidentally coincide with an identical symbol with identical purpose is laughable. Statistically,

given all possible geometrical forms, and given that only a tiny fraction of the humanity is even

familiar with the tamga tradition, the chances for elements other than circle, triangle, and a few

others is next to nil. As an example, the whole combined multitude of the Chinese, Japanese, Korean,

Mayan, Egyptian, etc. hieroglyphs may have only a few that resemble any of the combined tamgas of

the Scythians, Cimmerians, Sarmats, Huns, etc., but none of these few hieroglyphs would be a unique

identifier of a clan or a member of a clan, semantically these graphical coincidences will be

completely different. The point of the last item is to divorce the emblem of the Rus rulers from the

royal tamgas of the Kushans, Huns, and other Türkic dynasts by proclamation, by unsubstantiated

statistical assertion, i.e. by political and devoid of science proof. It is just another Potemkin

village. |

We would try to identify possible functions of the tamga-like signs on the example of the so-called Sarmatian

tamgas that

form one of most representative signs systems of early Iron Age. It is known that the Sarmatian (in the broad sense of the ethnonym) tribes

did not have their own

script, but were in contact with the highly developed sedentary civilizations who had their scripts. It is

universally recognized that information is a defining feature of any sign system.

To convey to the “viewers” certain information associated with a sign was to adjust appropriately

their

behavior: for example, cause a sense of alertness, etc. However, the expected effect was only

possible if the “audience” understood the meaning of the sign, that is to acknowledge it, seeing

as an external signal and a “call for action”. Thus, the most important function of the sign

(including tamga-like signs) is a signal acknowledgement.

| The whole steppe belt, from Pacific to Adriatic, where agriculture was not sustainable, was

adjacent to the areas, where agriculture was sustainable, and where the writing emerged in Sumer. It

was impossible for the steppe nomads not to be familiar with the concept of writing, not to interact

with writing, and not to learn writing. The mobile nomads were the agents of disseminating knowledge

and technology, including writing, across Eurasia, bringing writing to their sedentary frontiers.

That is attested by the Zhou nomads bringing writing to China, and Ases bringing writing to the

northwestern Europe, and probably Alans or Huns bringing writing to the forest zone of the Eastern

Europe to the Slavic peoples. The role of nomads in bringing enlightenment to the isolated sedentary

agricultural enclaves is known, attested, and does not need to be belittled by patriotic

semi-scientists. The part of on “signal acknowledgement” is too sophistic, not too subtle and too

specious. A tamga on a pot, on a cliff, on a coin says “me, I, mine”; a tamga on a gravestone says

“ours”, in every case it identifies an owner according to the traditional conventions, and does not

expect the viewers to heed a “call for action”. The circumstances other than seeing a tamga guide a

viewer to the action or inaction. |

Practically, depiction (marking) of a sign meant marking of a part of a certain entirety by its

deliberate marking that allowed to identify (classify) the marked part by both “markers” and “viewers”

and visually control it (am I controlling a penny just because it is marked

with a bust of Lincoln? What a primitive galimatia).

The need for such markers objectively exists in any society that perceives a simple opposition “us -

strangers”. It should be assumed that with the development of the social structure (splinter of the clan, professional,

etc. groups) and complexity of the linkage complexity between elements of the structure the need for such

symbol systems increases. However, the informational capabilities of the tamga-like signs are not

limitless; over time their application range should gradually taper off, switching to a better

information system, the writing. But a certain period of coexistence of the two systems is quite

possible and even inevitable. Further evolution of the tamga-like symbols usually lead to the heraldry (tamgas a kind of

“coat of arms”), religious (tamgas are sacred symbols), legal (tamgas are “certificates”, confirmation of the

affiliation, possession,

etc.) or traditional household sphere (tamga is an element of ornament).

| A quick look at societies with a tamga tradition and without it, like the ethnic Rumanians

(Vlakhs)

vs. Türkic-Rumanians, or ethnic Russians vs. Türkic-Russians would clearly demonstrate the futility

of such speculations. |

The “prototypes” of tamgas, according to the the available ethnographic data

(since only the Türkic ethnography notes tamgas as an ethnic marker, the

reference to the “available ethnographic data” is solely to the Türkic societies, or the societies

where the Türkic element were a ruling elite) were simple geometric shapes

(circle, square, triangle, angle, etc.), sacred pictograms, birds and animals, household items,

tools, weapons and harness, sometimes letters of different alphabets. Therefore graphemes (particularly simple

graphemes) of the many symbols could be used simultaneously or sequentially in parallel in several

geographically, culturally, and chronologically unrelated societies. The symbols were undergoing some

stylization unavoidable in marking selected surface with heavy tools (chisel,

knife, adz, etc.). The main requirement for a tamga-like sign was a graphic clarity and

laconism, and possibility of modification within the existing conventions.

So, probably, was accounted for that the regular use of the sign on different

surfaces (stone, leather, wood, etc.) would be easier if the sign was simpler.

| Branding tools were and still are made by smiths on order, and probably the simplicity of the

image and the desire of the customer had to find a balance. Any tamgas required authorization, be it

a head of the clan approving modification, a head of the tribal union (two kinship clans had to

share tamga, but the distinction between clans had to be apparent), the Prime Minister of the

confederation, etc., each according to his jurisdiction. Once established, tamgas took on their own

life, continuing the tradition. The cowboys that used tamgas had no clue of the sophistication

ascribed to them by the later desk scientists. |

Tamga-like or “Sarmatian” signs are an important element of the culture of many Sarmatian (Sarmatian -Alan) tribes. They are also interesting in that the direct predecessors of the

Sarmatians, Scythians and Savromats, did not know tamgas. The genesis of the Sarmatian

tamgas still remains unclear, but the available data allow to disclaim a priority of the Sarmatian

tamga tradition. Location of the “homeland” for the Sarmatian signs is hindered by their “scattering” resulting

from movements and migrations of the nomads. But the impossibility of the origin of the

Sarmatian tamga tradition in the areas of the N.Pontic, Volga (Itil)

and Ural is quite obvious. A most

likely hypothesis seems to be importation of the tamgas to the N.Pontic and Caucasia during migrations

of the Sarmatian

groups from the Middle Asia, where a tradition of using tamga-like signs long existed. In

the ancient societies of Eurasia the literacy and writing were a privilege of the social elite,

while all sectors of society could use signs due to their relative simplicity; this

circumstance, together with others, was creating good conditions for the spread of the tamga systems

among the illiterate nomadic

peoples.

| The Sarmatian origin is classified as Tasmola archeological culture, aka Bobrov-Tasmola

archaeological culture, which concluded that origin of the Sarmatians is a result of amalgamation of

the Middle Asian Huns and local population of Central Kazakhstan. Essentially, archeological studies

suggest a Hunnic origin of the Sarmatian tamgas. The “scattering” is innate for the mobile nomadic

societies, that is what distinguishes the sedentary and nomadic society. The blurb in literacy -

illiteracy, and their advantages for the spread of tamgas is ahistorical propaganda nonsense.

Nomadic societies, in contrast with sedentary societies, were intrinsically egalitarian and

meritocratic. |

Among the Sarmato-Alans, tamgas image are usually found on objects from the rich burials, and rarely

from the ordinary burials, that

can be seen as an evidence of the predominant tamga use by the nobles. However, there is no evidence that tamgas

were used

exclusively by the Sarmato-Alan elite. Such a situation might occur, but it appears only at an

early stage; the poor nomads could mark the tamgas on poorly preserved organic

objects. The spread of tamgas among the the nomads was driven by a need to tag stops on their

pasturing routs, their pastures,

and to brand cattle to demonstrate their ownership. So, the signs posted on the cliff passes were quite durable, and most importantly

they were understood by all members of a specific society

regardless of their social status. The branding of the cattle was the only “cheap” and reliable way to

mark their owners.

| An utter ignorance of the Sarmato-Alan religion of Tengriism, and its necessity to equip a

deceased with a travel necessities for a trip to Tengri for reincarnation underlies the bunk

speculations and irrational conclusions. What we see in the funeral inventory is a mirror of the

deceased's household, because the family of the deceased supplied the deceased with the same

inventory that he or she used during lifetime: his transportation (horse, wagon, harness), his

dishes, his table (taskak), his dress (belts, ornaments), his arms (arrowheads), plus the donations

of the those paying respect at the funerals. A rich or high official household may have their dishes

monogrammed with tamgas, an ordinary household that did not conduct diplomatic or social receptions

did not monogram them. The misinterpretation of the funeral inventory in the Russian science was

institutional, based on intentional ignorance of the Tengriism, and driven by an objective to find

support for the Avesta and its interpretations. Even the terminology is particular and flawed: a

Hunnic, Bulgarian, Türkic etc, tamgas are tamgas, but the Sarmatian tamgas are “signs”, “tamga-like

signs”, and the like euphemisms. The definition “Sarmato-Alan” is as vague as they come: The

attributions to the “Sarmato-Alan”, “Sarmats”, “Alans”, “Scythians”, and “Saka” is done based on the

vague notions of the “Sarmatian time”, “Scythian time”, “Saka time” formulated from the literary

sources, from the typological assessments, and with extensive complains that the chronological

typology does not work for mobile societies. Even the distinction between the Scythians and

Sarmatians has been established only conditionally, the archeology does not offer any clear-cut

criteria. Of the modern testing and computer technology only one

tool is used, the “garbage in, garbage out”. Fortunately, such debased science is on the wane, and

the real scientists lead the change. |

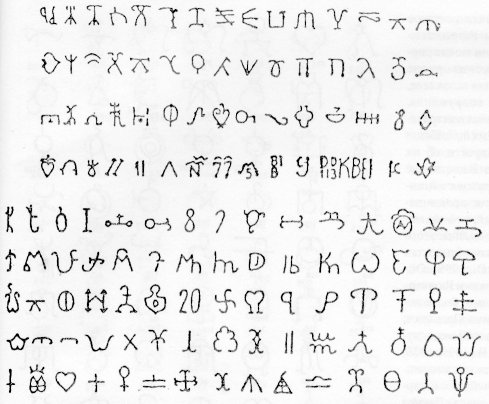

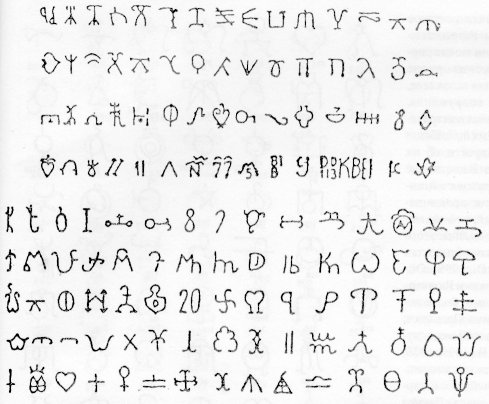

To date, were identified hundreds of versions of the Sarmatian signs on the natural objects, household

items (dishes, mirrors, musical instruments, etc.), clothing, jewelry, weapons, art monuments,

tombstones, coins, objects of worship, architectural, religious, burial structures etc. In some

cases, these tamga-like signs occur in clusters numbering from few tens to hundreds.

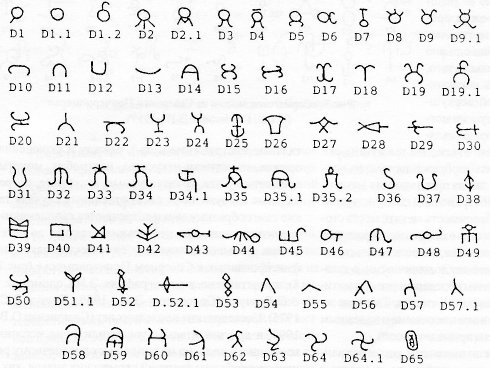

A large number of Sarmatian signs recorded in the N.Pontic region

(Fig. 7, 8) is presented in monographs of E.I. Solomonik and V.S. Drachuk (Solomonik E.I., 1959; Drachuk B.C., 1975). The studies

of recent years (Simonenko OV, 1999, and others) significantly increased the source base, but did not result

in unambiguous solution of the problem of the Sarmatian sign functions, and of the tamga-like signs

in general (Vasiliev D.D., 1998).

| The statement on the problem to be solved is buried in the introductory portion of the article:

“the role and functions of the signs, including tamgas”. Obviously, the solution that the author, V.S. Olkhovsky,

is aspired to will never be found: that is the difference in the use of tamgas between the

Iranian-speaking Sarmats of the Scytho-Iranian Theory, and the real Eurasian Sarmats. The only

“solution” advanced so far is the ingenious insight of S.À.Yatsenko: the Türkic tamgas have a

nickname, and the Iranian don't. For a sober person that would be a positive indicator of the

cultural borrowing, but such an admission would have brought about a storm into the reigning

paradigm, and may unfavorably affect the author himself. So the possibility of the cultural

borrowing was not even mentioned, unlike the present article that admits that the Sarmatian tamgas

were a cultural borrowing. So, the non-existent problem remains “unresolved”. |

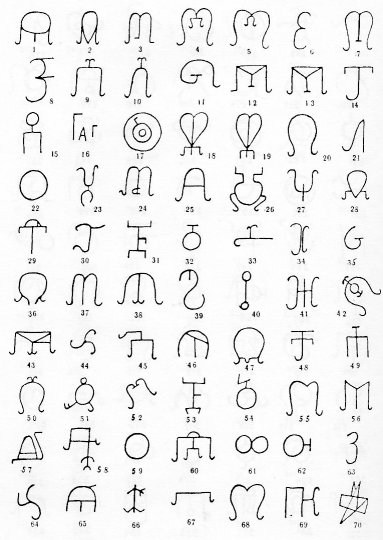

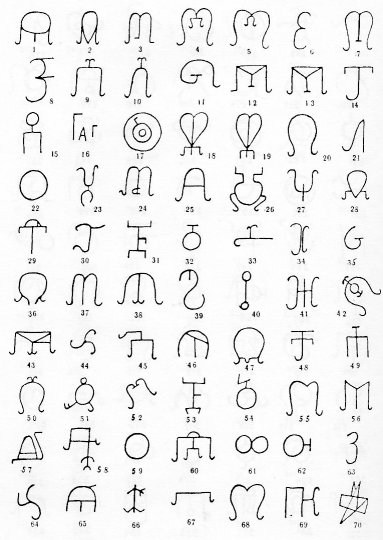

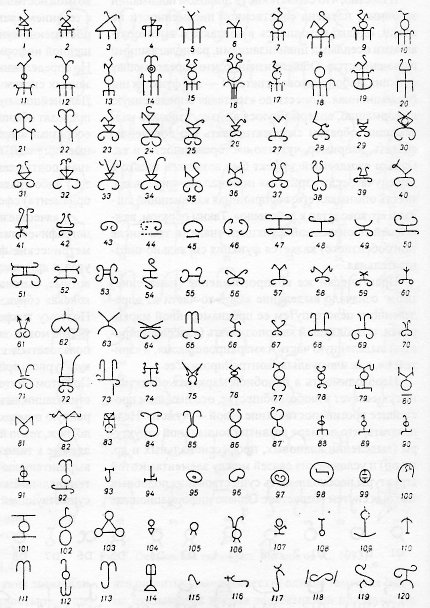

Ðèñ. 7. "Ñàðìàòñêèå çíàêè" èç Ñåâåðíîãî Ïðè÷åðíîìîðüÿ

(ïî: Ñîëîìîíèê Ý.È., 1959) |

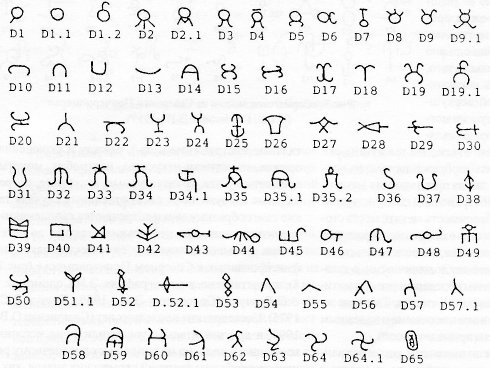

Ðèñ. 8. "Ñàðìàòñêèå çíàêè" èç Ñåâåðíîãî Ïðè÷åðíîìîðüÿ

(ïî: Ñîëîìîíèê Ý.È., 1959) |

Fig. 7. "Sarmatian signs" from the North Pontic region

(after Solomonik E., 1959) |

Fig. 8. "Sarmatian signs" from the North Pontic region

(after Solomonik E., 1959) |

|

|

It seems that the available materials give reason to expect a polyfunctionality of the Sarmatian signs

even within a framework of a single ethno-cultural community, but with a preservation of their main signal

and identification function.

1). Tamga is a sign of belonging (ethnic, collective, most commonly

personal). The attribution problem, the specific

“owners” of the signs is very difficult. From the later ethnographic parallels, patterns of the

tamga use, the tamgas can be interpreted definitely enough as the signs of personal or group affiliation. If

a tamga was a

collective identifier, any member of the group was a “carrier” of their sign, which in practice turned

also served as a sign of individual affiliation. The collective owner of the tamgas could be a family,

kinship, clan, tribe,

or tribal group. Affiliation of the members with the same “tamga” was setting them apart from the mass of other

individuals, meant that they belonged to “their” folks and signified their distinction from the “others”. Did all

the members of a family or clan group had a right to the “family” tamga, and under what circumstances they used it without

changing the grapheme, these are just some of the questions with difficult to

obtain answers. Thus, in this case was tamga was a signal and identification symbol of the kinfolks (real or fictitious),

and was applied to clan's flags, shrines, etc.

| Mentioning of the flags is funny: a flag is a field army signal emblem, and no clan was an army. |

2). Tamga is a sign of ownership. With a large doze of probability can be expected the use of tamgas as “tracer tags”

certifying the fact of possession of territory, property, cattle. Who specifically (kins, family,

clan, tribe, or individual) was the owner of the object with tamga image was determined by the

first tamga function (sign of membership). So, among a number of Iranian and Caucasian peoples,

tamgas were marks of clan ownership of livestock, land possessions, and religious objects. Also, quite possible

is the use of tamgas as a mark of personal possession of valuables (weapons, jewelry).

This is supported by discovery in one burial of several objects marked with the same type of tamga (Simonenko A.V., Lobaev B.I., 1991, p. 62, 63).

3). Tamga is a sign of authorship. Probably, this use of tamgas was not widespread, it was a master's

mark for especially valuable object. However, in this case is not excluded a possibility of initial

marking of the customer's tamga (future owner) instead of the manufacturing master.

4). Tamga - a sign of the of (territorial) presence. Detection of tamgas in places that are

difficult to deem as probable someone's “property” (architectural structures of the Hellenic cities,

cliffs, Greek sculptures, etc.), as well as the presence of large tamga clusters in

limited areas, allows to conceive a possibility of tamga use as marking of presence of

different family and tribal members at a certain place. Possibly, a visit to these places was

accompanied with marking tamgas on natural or artificial stone surfaces was marking events of a

political, military or religious nature, important for large Sarmatian etno-tribal associations.

5). Tamga is a certificate (personification) mark. This function suggests the use of tamgas as

a “badge”, as a personal

“signature”. More than likely is the use of tamgas by the highest Sarmatian and Bosporus nobility.

Positively enough were identified the personal tamgas of the Sarmatian kings Farzoi, Inismei, Bosporan kings Rimitalk, Tiberius Eupator, Sauromates II, Reskuporid

III, and others (Fig. 9). The royal tamgas on the coins,

their inclusion in the texts of the royal decrees apparently was equivalent to the royal seal.

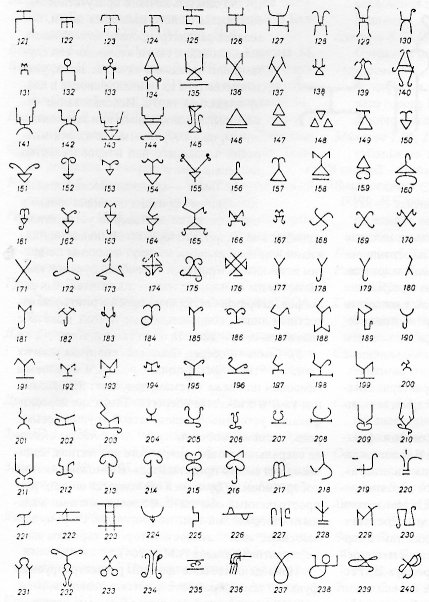

Ðèñ. 9. Çíàêè-òàìãè áîñïîðñêèõ öàðåé:

1 - Òèáåðèÿ Þëèÿ Åâïàòîðà; 2 - Ñàâðîìàòà II; 3 - Ðèñêóïîðèäà III; 4 -

Èíèíôèìåÿ

(ïî: Ñîëîìîíèê Ý.È., 1959) |

Fig. 9. Symbols-tamgas of the Bosporan kings:

1 -

Tiberius Julius Eupatoros; 2 - Sauromatos II; 3 - Rheskopurides III; 4 -

Ininphimeus

(after Solomonik, E., 1959) |

|

| Intentionally or not, the tamgas No 1, 2, and 3 are shown upside down. They are tridents, with

individual modifications. More than that, the tamgas of the first Kushan royals is identical to the

tamgas of the Bospor royalty, indicating a close family connection between the Sarmatic dynastic

clan of the Bospor state and the Huna house of the Kushans. One has to be blind to miss it. Tamga no 4 appears to be a portion of the Horezmian tamga, known from

numerous coins. |

6). Tamga is a sign of patronage and submission. Detection of the Sarmatian noblemen (including

the royals) tamgas on low-value objects or in places where it is difficult to expect a personal presence of

a high-ranking tamga owner allows to read the use the “master's” tamgas by his servants or

dependents as

a mark indicating their belonging to the tamga owner's clan. Use of someone else's tamgas by subordinates

or dependents thus could mean a transfer under the patronage of the tamga's owner.

7). Tamga is a chronological indicator. This function is only apparent when is well established

the ownership of tamga by a historical person, the years of life or activities of whom are known from other sources. Examples of

such tamga function are votive reliefs with dated texts, decrees of the Bosporus kings, and epitaphs

to the known

persons accompanied with tamga, or coins with the name of the dynast and his tamga, etc.

8). Tamga - talisman, amulet. The complex semantics of many tamgas, especially ascending to the ancestral cult

symbols or even totems, admits a use of tamgas as amulets. The tamga as a personification of

sustained human group (family, clan, tribe) and could act as a symbol of a sacred power of a

particular group, protecting its member. Perhaps it was a “protective” function of the tamgas that explains

the widespread Sarmatian and Alan

custom of depicting tamga images on the reverse side of the mirrors, which sacral

significance is quite likely among the Sarmatians (Khazanov A.M., 1964).

The above examples of reconstructable functions of the tamga-like Sarmatian signs may not cover the full

diversity of their use in ancient times. New materials and future research would obviously clarify our

understanding of the nature and mechanism of the functioning of the sign systems, a very

important historical source.

|