Kayi and Gelons, Nasidze 2010

Proceedings of the Academy of DNA Genealogy, ISSN 1942-7484, Volume 5, No. 8 August 2012, pp. 1013-1019

Appendix: W.W. Bartold, ON THE ORIGIN OF KAYITAKS, Vol 3, pp. 411 - 413

| Türkic folks - Kayi and Gelons | ||

| N.Kisamov Kayi and Gelons, Nasidze 2010 Proceedings of the Academy of DNA Genealogy, ISSN 1942-7484, Volume 5, No. 8 August 2012, pp. 1013-1019 Appendix: W.W. Bartold, ON THE ORIGIN OF KAYITAKS, Vol 3, pp. 411 - 413 |

|

|

|

Links |

||

http://aklyosov.home.comcast.net/5_8_2012.pdf |

||

|

PDF files |

||

|

|

||

|

Introduction |

||

Popular reference sources depict Kayi as a mysterious people, appearing in numerous places across Eurasia at flash points, attracting attention of the passers-by. A staple of information is W.W. Bartold's On the origins of Kayitaks//Ethnographic Review, 1910, No 1-2, Moscow, pp. 38-40, which gave a brief review of few sources, and is woefully inadequate. In somewhat more detail Kayi were addressed in S.A. Pletneva's Kipchaks, Moscow, “Science”, 1990, in the narrow time range of Kipchak migration to the Eastern Europe. The references to the Kayi nevertheless are abundant, covering a span of nearly 25 centuries, and a space of most of the Eurasia. Although the Kayi's role in the Eurasian history is most prominent, its treatment is way under par. An Ottoman traveler Evliya Chelebe (1611 – 1682) remains one of the few cited sources that left more than a political outline of events. Under these circumstances, a population geneticists study that specifically attends to the group of Kayis in the Caucasus mountains known as “Mountain Kayis” Kaytags is most welcome. It allows to peak into their past from a different angle. Undoubtedly, the study corroborates the litany of the historical sources, and conflicts with later historical re-writes. The posting's notes and explanations, added to the text of the author and not noted specially, are highlighted in blue font, shown in (blue italics) in parentheses and in blue boxes. Page numbers are shown at the end of the page in blue. |

||

| N.Kisamov Nasidze’s Kayi and Gelons |

||

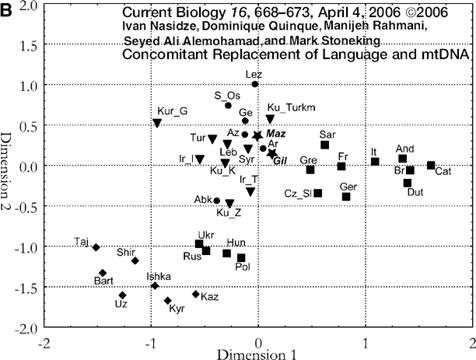

The article by Ivan Nasidze et al. [I. Nasidze, D. Quinque, M. Rahmani, S. A. Alemohamad, M. Stoneking, Concomitant Replacement of Language and mtDNA in South Caspian Populations of Iran (Report)", Curr. Biol. 16, 668-673, 2006, http://www.kavehfarrokh.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/03/nasidze.pdf] includes a Figure (Fig. 2B) that links Y-DNA of “Gilaki”, “Gilani”, “Mazandarani” with Azeri and other Turkic people. This is the most interesting observation, which corroborates the known historical flow of events. It allows to peek into the genetic composition of the Western Scythians. The Scythians east and west of Caspian sea from 1000 BC to 500 BC were known as As-guza, the Hebrew Ashkenaz. They settled in Azeri-land, and Herodotus called a northern branch of them Gelons, while the southern branch on the southern bank of the Caspian was called Gilans. Now they are “Gilaki” and “Gilani” of Iran. They must have been of the same haplogroup (Y-hg) as the Azeri, and in fact they were Azeris. 3000 years later, they still carry the same ancestral biological markers.

A group of Gilans became a marital partner of the Eastern Huns (probably when the Huns were

primarily located in the Pamirs and Taklamakan/Taklimakan, much closer to the Caspian-Aral area), and gained a

Mongolic calque-name Kayi, both terms Gilan and Kayi meaning Snake. When the Huns abandoned Kayi as

a marital partner in favor of the Uigurs, the Kayi split, and a part of them under a name Kayi returned

to the Gilan area. While the Kayi women married the Huns, the Kayi men had to find a female

partner-tribe, probably they came back with their women, but they brought back their original Y-DNA

markers. They may have returned later, after the events of the 93 BC. By 150 AD, Kayi were

well-established between Sakasena and Gilan, they are called at that time both Kayi (Arm. Hai) and

Huns. They were not too friendly with their cousins Gilans, their political histories were quite

separate. But their Y-DNA occupied territory from Derbent (and 100 km north of Derbent) to Hyrcania

along the Caspian sea coast. The terrain was marshy, much like in the Aral deltas, from which

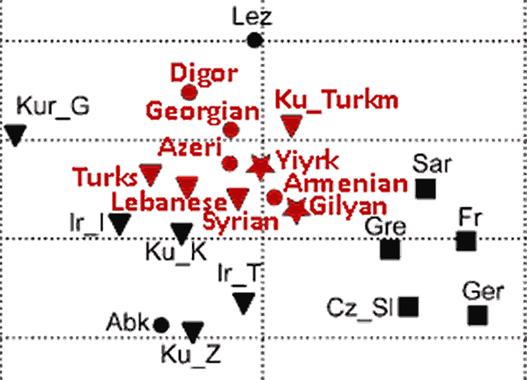

apparently arrived their ancestors Scythians - As-guza - Saka. Mazandaran is a political name, its ethnic name was Hircania (Hyrcania) in a Greek form, in Turkic literally “Nomadia”. The Russian form is Ûéèðê, in English usually spelled Yiyrk, but in Turkmenia and in Turkey they have slightly different spellings, now they are quite substantial tribes, Yürük (Russ. Þðþê) and Yörük. They occupied more deserted part of the coast, had to migrate more, and although culturally and genetically being the same as Azeri and Gilans, they were called with a distinct name, which produced the Greek Hyrcania. Their Y-DNA occupied territory from Gilan to Mangyshlak and then along Uzboi to the Aral Sea. On the Nasidze et. al. 2006 scheme we see it as identical with Turkmenistan Y-DNA, neighboring Gilan Y-DNA, and genetically as far from the Azeri DNA as they are far geographically. Figure 2. Multidimentional Scaling Plots.

A closer look at the immediate neighborhood of the Gilyans and Yiyrk produces a telling picture.  Abk, Abkhazians; Ar, Armenians; Az, Azeri; Cz-Sl, Czech & Slovaks; Fr, French; Ge, Georgians;

Gilyan (Gilani, Gilaki); Gre, Greeks; Ku_G, Kurds from Georgia; Ku_I, Kurds from Iran; Ku_K,

Kurmanji Kurds; Ku_ Turkm, Kurds Turkmenistan; Ku_Z, Za-zaki Kurds;

Leb, Lebanese; Lez, Lezginians;

Yiyrk Os_A, Ossetians from Ardon; Os_D, Digors "Ossetians", S_Os,

Although the ethnic picture is distorted by combining political definitions conflated with ethnic definitions, nevertheless the analysis corroborates numerous historical links. The most prominent is the close connection between the Yiyrks of the Mazandaran province and the Azeris of the Azerbaijan, which inevitably include some distortions from layers of different ethnicities. On the level of population genetics, the close proximity of the two points to a common origin. Most of the Yiyrks migrated with the Seljuk, Ottoman, and later movements, ending up in Anatolia, the Yiyrk sampling in Mazandaran represents somewhat diluted remnants of the population at the turn of the eras. The trio of the Azeri, Yiyrks, and Gilyans (under local names of Gilani and Gilaki) indicates a former ethnic continuum of As-guza Scythians, noted in a strip extending from Sakasena to Aral Sea, the As tribes specifically in Sakacena as As-guza and Saka and around Aral as the As tribe of the As-Tokhar confederation after their expulsion from the Chach area and before their excursion into Bactria; Yiyrks as Hyrcans of Hyrcania along the Caspian coast, and Gilyans between the Sakacena and Hyrcania. The genetical proximity of the Azeri-Yiyrks, Armenians, and Gilyans reflects the early contribution of the Turkic nomadic tribes to the Armenian genetic pool in the Caucasus. The Caucasus Agvania (aka Albania) included the early Armenian population and the tribes of the Huns and Masguts (Greek Massagets, later called Alans), and also the Huns specifically identified as the tribe of Kayis, known under numerous close phonetical variations: Haidak, Kaitak, Haidan etc. Being an eastern leg of the Gilyans, the Kayi males had to share Y-DNA with the Gilyan males, their incursion into the Tarim basin and sojourn with the Huns should not have impacted their male Y-DNA marker. The super-ethnonym Masguts likely referred to the same Yiyrk nomadic tribes as their component, and probably also descended from the Scythian As-guza tribes that produced the Near Eastern As-guza. Before the appearance of the As-guza in the Near East, the Aral basin was re-populated by the horse nomads, one component of which was the nomads from the east whose kurgan burials were positively traced and dated on their way from South Siberia toward the Europe. Time wise, the expansion of the Armenians in the Caucasus falls in-between the early Scythian and later Kayi Huns' migration to the same areas.

The Y-DNA Fst diagram also indicates approximately equal contribution of the Yiyrk-Azeri blood to the Georgians and Turkmenistan Kurds. The Turkish, Lebanese, and Syrian samples reflect a composite nature of these countries. The Turkish sample reflects a significant portion of the Yiyrk- and Kayi-derived population, as indicated on the Turkish ethnical maps. A more precise sampling along the ethnical lines would make the parallels more crisp. http://www.anadoluasiretleri.com/Page.php?pid=10

Yörük Kayı The relative proximity of the Türkic Scythians with the Greek and French is outwardly unpredicted, but on closer examination finds transparent historical explanations. Herodotus noted a very specific Greek connection with the Gelons, he called the population of a Gelon city half-Greek, half-Scythian, reflecting an apparent status that numerous Greek people already populated N. Pontic area before the 5th c. BC. Another substantial contribution of the nomadic genes was more direct, by the Scythian migrants to the Greece, and by the Scythian mercenaries in the Greek armies over the centuries of the Classical period. Both the intensive nomadic migrations and intensive Greek movements around the N.Pontic would have facilitated a high degree of genetic exchanges. France experienced two distinct and significant waves of nomadic admixture, when the nomads established polities that eventually integrated into the French people. The first wave was that of the Amorican Alans in Brittany. The name "Alan" is a generic name similar to the ethnonym Yiyrk "nomad", Hun "kin", or Türk "of Türkic people", the name Alan means "steppe people" or "plain dweller". A part of the Alan confederation were the As tribes, hence the past conflation of the terms "Alan" and "As". The second wave was that of the Burgunds in the south-east of the modern France, that was also a long-lasting and sufficiently numerous symbiosis to leave a genetical imprint noted in the analysis of the population genetics. A stand-apart, but still in the immediate proximity fall the Digors, presently dubbed “North Ossetians” in accordance with the political affiliation and administrative division. The non-Digorian Ossetians call the Digors’ neighbors Karachais Harases, a local phonetic form of the name Kara-Ases meaning “Black Ases”. The term “Black” still carries a connotation of “lowly”, like in Russian “×åðíàÿ êîñòü” – “Black bone”, signifying a non-noble, an opposite of the “Blue blood”. In the Türkic societies, that was a term for subordinated people and tribes, tributaries, and the members of that class. In the As-Tokhar confederation, the Tochars were a “Black” subordinated tribe of the dynastic Ases, or Kara-Ases, where As serves as a super-ethnonym. The Tokhars were sufficiently close to the Ases (not the Caucasus Ases, but the Caspian-Aral Ases) for more than a millennia, plenty of time to incorporate statistically significant proportion of their male DNA. On the other side of the Caspian their namesakes are called Dügers, they are one of the Turkmenian tribes, and in the literature they are identified with the forms Tokhars and Tuhsi. The genetical affiliation of the Digors with the Ases-Gilyans/Gilaki is a logical consequence of their extended marital union. The genetic analysis corroborates the historical link between the Inner Asia Ases and Tokhars. Probably, the most important contribution of the statistical analysis is that it points to the directions of the future research. Due to the potent traces left by the Kayis in the historical period, the DNA-genealogy may be able to trace the progression of the Y-DNA carriers in time and space . Linguists may uncover the reasons for the differences between the “Gilaki”, “Gilani”, and “Mazandarani” vernacular and the Persian language of the modern Iran. |

| W.W. Bartold ON THE ORIGIN OF KAYITAKS Published: Ethnographic Review, 1910, ¹ 1-2, pp. 37-45; ¹ 3-4, pp. 283-284 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

This article reproduced, in a much enlarged form, an author's report at the meeting of the

sub-section of ethnography at the 12th Congress of Russian Naturalists and Physicians in Moscow,

1909-1910. (See also the edition W.W. Bartold, Works in 5 Volumes, Vol 3, pp. 411 - 413)

ON THE ORIGIN OF KAYITAKS Despite the progress made in the last decades (1880s-1900s) by the Caucasian studies, the linguistic and ethnographic issues related to the study of the Caucasus are far from sufficient, and the material available for the scientists remains extremely poor. In the scientific world a particular interest aroused attempts to link the Caucasian languages with the non-Aryan languages of ancient and non-Semitic civilized peoples of Asia Minor, particularly with the language of the so-called second system of the Achaemenid cuneiform inscriptions. Unfortunately, in this case scientists are forced to link modern languages with the language of the monuments, of which the latest are of the 4th BC; yet from the words of the Arab geographers we know that the ancient population of Khuzestan spoke that language as a living language in the same area in the 10th century AD (Compare the words of the geographer Istakhri (91): "With regard to their (Khuzestan residents) language, the common people speak Persian and Arabic, but they have a different language, Khuzean, not identical with the Jewish, nor with Syrian, nor with the Persian"). The same lack of linguistic records hinders another difficult question of the Caucasus historical ethnography: how people of the three broad linguistic groups, approaching the Caucasus in the historical time from the north and from the south, the Iranians, Turks, and Mongols, impacted the Caucasian languages, or themselves were subject to the influence of the latter. Now, as you know, one of the Turkic languages, the Azeri, becomes more and more an important lingua franca for a large number of Caucasian peoples; it is possible that in earlier centuries were also examples of the opposite phenomenon, namely, that the alien elements, thrown among the Caucasian peoples, linguistically submitted to the influence of their neighbors. Unfortunately, prior to the European scientific expeditions, that is, until the second half of the 18th century, travelers who visited the Caucasus do not tell us, with most insignificant exceptions, any information on the lexical structure [370] of the Caucasus languages. One of the rare exceptions is the 17th century Ottoman traveler Evliya Chelebi (Çelebi), who included into description of his travels through Asia Minor and the Caucasus a rather large word lists in several dialects, and thus is giving us a precious linguistic material, still not used by the scientists (The Evliya Chelebi work is called Siyahat-name (literally "Description of travel"). Information about the fate of this work and the nature of the only existing edition (Constantinople) are given in the introduction to the V.D. Smirnov anthology (Sample masterpieces, pp. VII et seq.). One of the nations that draw the attention of the Ottoman traveler were Kayitaks, whom he saw in 1647 on the way from the city Shekki (now Nuha) (Sheki, Saki, Shaki, Nukha, Nuha, Nuha Sumgait, Sumqayit in Azerbaijan, 40.6°N 49.7°E) to Shemakha (Şamaxı, Schemacha, Shamakhy, Shamakhi and Shemakha in Azerbaijan, 40.6°N 48.7°E) and of whom he reported by the following information: (See: Evliya Chelebi Siyahat-name, 2 , p. 291 et seq.; Smirnov, Sample masterpieces, p. 95 et seq.) “Description of the Kayitak tribe. - In this area is a tribe called Kayitaks, whose number reaches 20,000. Their country is in the limits of of Dagestan; from time to time they come to trade to the Aras cities (described by Evliya Chelebi slightly previuosly in the description of the road from Erivan to Shekki (Nuha), with a notation (Siyahat-name, II, 288) that "the name of the city is pronounced Aras Following this, the author gives a list of "words and terms of the Kayitaks, who are a branch of the Mongolian people", and ends the chapter on Kayitaks with the following remark: "They still have many more terms, but we are content with this number; a hint is enough for a knowagable (Arabic proverb). According to [371], in origin they are Mongols, who came from the Mahan (?) area; they are Turks, they speak in Mongolian, Turkish and Mongolian languages - one and the same. (!) We have seen this tribe in the area Mahmudabad. " As for the list of the words, it becomes more difficult to use for the properties of the Arabic alphabet, moreover because the Constantinople edition in respect of proofing is by no means reliable, let alone any compliance with philological criticism. The list has 41 words, 36 of them are animals. Up to 16 names are purely Mongolic (Not knowing the Mongolian language, I could explore this word list only with the kind assistance of my former student B.Ya. Vladimirtsov), namely the following: Highlighted words agree with the Kayitag's forms; Türkic column is added in this posting

Among other words are Turkish (Djiran - antelope, sykyrcha - cricket, alachin - falcon), and absolutely inexplicable, very likely that a significant portion of these words was distorted by copyists (Mongolian names of animals gives, also in the Arabic transcription, a Persian author of the 14th century Hamdallah Qazwini in his geographical work. Comparing Hamdallah Kazvini and Evliya Chelebi spelling shows that apart from the above animals "spider" and "crocodile" also were called by Kayitaks with the same terms as those of the Persian Mongols of the 14th c.; but determine pronunciation of these words in Arabic transcription is hardly possible). In addition to the animal names, are cited the words: djakdjay (or chakchay) - broad steppe (?), Surhan - a name of a king (possibly, Mongolian Sürhen - terrifying), shenb - cemetery, shenbtai - cemetery guard, djad - enemy. Especially interesting is the word shenb, now completely unknown in Mongolian, but undoubtedly existing in the Middle Ages; Shenb-i Ghazan Khan was called a village [372] in Azerbaijan (On that village see Barthold, Historical and geographical overview of Iran, page 146) , where was a tomb of the famous Mongol ruler of Persia, Ghazan Khan (1295-1304). Evliya Chelebi's information about Kayitak language would be of greater interest if in this case he, like in some other cases (Like listed in the same volume word lists for Georgian and Mingrelian (Evliya Chelebi Siyahat-name, II, 319, 359)) , had included in his list the words even for pronouns and numerals; but even the number of the Mongol words that we find in this list is a pretty strong argument in favor of Mongolian origin of the Kayitaks, the more so that these words could not be invented by the author, who did not know Mongolian language and even did not distinguish it from the Turkish. These Mongols were Muslims, hence they could not be from among the Kalmyks, who besides that in the first half of the 17th century still were not in the area adjacent to the Caucasus main ridge. Obviously, the Dagestani Mongols, could only be the descendants of immigrants from the Kipchak Khanate or the Persian Ilkhans state. I can not understand what locality is meant in our text under "Mahan" (Obviously, there can be no question about the famous Mahan in Southern Persia, in Kerman). In the Mongol era Derbent apparently more frquently belonged to the Kipchak Khanate khans than Persian Ilhans, therefore more likely the ancestors of the Mongolian Kayitaks came to Dagestan from the north, especially as the first historical news about Kayitaks calls them supporters of the Kipchak Khanate Khan. To my knowledge, tor the first time Kayitaks are mentioned in a story about the struggle between Timur (Tamerlane), and Tokhtamysh in 1395 (That episode is mentioned in the first edition of the official history by Nizam al-Din Shami and compiled during the life of Timur (Brit. Museum manuscript Ad. 23980, p. 1136), and in a more known work of Sharaf al-Din Yazdi (I, 742). Going through Derbent, Timur at the foot of the Elburz mountains (i.e. the Caucasus Ridge) (In this same sense the word Elburz is used by Evliya Chelebi (Siyahat-name, II, 293). Nizam al-Din Shami also added: "at a distance of 5 farsahs (i.e., 25-30 km) from the sea shore") met Tokhtamysh's Kayitak supporters. On Timur's order his men surprisingly attacked these people "without faith", and completely clobbered them; only one out of thousand survived; all Kayitak villages were burned up. From the words of the historian, who calls Kayitaks the people "without faith" (bi din) or with "bad faith" (bad kish), can br concluded that at that time Kayitaks were not considered to be Muslims. Even in the second half of the 15th century a Venetian Barbaro wrote about Kayitaks that many of them are Christians of the Greek, Armenian, and Catholic denominations (Ramusio, Viaggi, II, 109a. The Barbaro's news is also found in the E. Veidenbaum's book Guide to the Caucasus, page 113). However, [373] from the story of the Barbaro's contemporary, a Russian merchant Athanasius Nikitin is clear (Cited in the E.I. Kozubsky's book (History of Derbent, page 51)) that at least the head of Kayitaks (Khalil Bek) had a Muslim name and was brother-in-law of the Shirvanshakh. When a Russian ship was cast ashore on the way from Astrakhan to Derbent near Tarki (Mahachkala), Kayitaks captured its crew, but then Khalil Bek, at the request of Shirvanshakh, voluntarily released all prisoners to Derbent. Kayitaks have not preserved ancient legends about the origin of the Kayitak people.

The Muhammad Avabi Derbent-name (91) tells about adoption of Islam by the Kayitaks still during Abu Muslim (8th century), about the origin of the lords Kayitak rulers, Utsmies, from the Arab Amir Hamza, appointed by Abu Muslim. The timing of this work in the version that has come down to us is not known, but in any case, it was written no later than 17th c., because the manuscript in the Imperial Public Library Dorn 541 is dated by 1099/1687-88), and the origin of the title Utsmi comes from the Arabic word ismi “eminent” (ism "name" (On that, for example, Dagestani, Kitab-i-Asar-i Dagistan, 34 (see next. note))) bears all the hallmarks of a very late book fiction.

The first Utsmi mentioned by historical records apparently should be recognized Sultan Ahmed, who died in 996/1587-88 (We use the book Asar-i Dagistan ("Traces of the past in Dagestan"), compiled by a Kürian Mirza Hasan-efendi in Azeri vernacular and printed in St. Petersburg in 1312/1894-95 on the means of the Baku millionaire Tagiyev (but the censorship permit is dated August 5, 1902) The main source for Hasan-efendi was a book Gulistan-i Iram ("Paradise flower garden" ~ "flower of Eden") by the official in Russian service Abbas-kuli of Baku, composed in 1841 in Persian and translated in 1844 to the Russian language. I have not seen copies of the Persian original; the Russian translation is preserved in a manuscript custody of the Tbilisi Public Library (Russian translation was published in 1926; see Bakikhanov, Gulistan-e Iram. On the Kitab-i-Asar-i Dagistan and its author, see present ed., Vol III, p. 418). He is attributed the foundation of the village Majalis (the Arabic plural of majlis "assembly", "meeting"), where came the inhabitants of the surrounding villages to discuss their affairs;he also compiled and offered as a guideline to the kazies (judges) a codex of regulations of the local customary law, in what the Dagestani historian sees "great boldness" (Dagestani, Kitab-i-Asar-i Dagistan, pp. 64-66. The Russian sources ascribe the compiling of such codex by Utsmi Rustem, which belongs to the 12th c., see Veidenbaum, Guide to the Caucasus, p 110). Sultan-Ahmed was succeeded by his son Mohammed; at the beginning of the 17th c. the Utsmi was already a Mohammed son Rustem; in the story about the war between Persians and Turks, the Utsmi Rustem is mentioned as a zealous ally of the Shah Abbas, generously rewarded for his help in the during Persians' capture of Derbent (Dagestani, the Kitab- Asar-i Dagistan, p. 75. On the Utsmi's role also speaks a contemporary of the events, a Persian historian Iskandar Munshi, without mentioning the name of Rustem, but only calling the Kayitak ruler Utsmi-Khan. The Dagestani historian clearly used the story of Iskender Munshi. See this story at Dorn Beitrage, Bd II, p. 50) (Year 1606). Rustem ruled for a long time; in 1638, [374], already during the Shah Safi regn, he betrayed the Shah and entered into communications with the Sultan; then Shah advanced Shamkhal Surkhay-Mirza against him. At the same time (by the words of the historian, in middle of 11 c., i.e. around 1640s) rose disturbances among the Kayitaks; one of the defeated party, Hussein Khan, managed to escape to Salyan and become a Khan of Salyan and Kuba, he submitted the Persian government and took Shiism. In 1688 he started a war with an Utsmi Ali-Sultan, and seized a Kayitak district, but then Ali-Sultan with a help of Shamkhal managed to regain his possessions. Hussein fled to Kuba, where he died ( Dagestani, Kitab-i-Asar-i Dagistan, pp. 81-83). These historical news seem to allow to explain satisfactorily the fact that Evliya Chelebi met Kayitaks much to the south of the area where they live now, and where they lived in the 14th and 15th centuries. But even assuming that Evliya Chelebi under the name Kayitaks describes people of some other nationalities, even then remains a curious fact that in the middle of the 17 c. in one of the Caucasus areas among the Muslim population was a nation in whose language remained purely Mongolian words for the domesticated animals (dog, horse, mule, ox, camel, pig, chicken), and prey animals (wolf, hare, squirrel, sable, partridge, quail). At present, such traces of the Mongolian language among the Caucasus vernaculars, as far as it is known, no longer exist.

In this connection, ethnographers' attention should be drawn to the need for speedy studies of the last vestiges of those Mongols, who in the era of the Mongol invasions separated from the main mass and remained outside the influence of Buddhism that has left its mark on the entire way of life of the inhabitants of Mongolia. The vast conquests of Chingiz Khan and his successors, as is known, did not lead to the expansion of the territory where Mongols gained ethnographic dominance; beyond Mongolia proper, where a majority of the population, according to all indications, spoke Mongolian before Chingiz Khan, the Mongols quickly adapted to the linguistic and ethnographic influence of the more cultured peoples.

Of the Mongol descendants, who in the 13 c. conquered Near East and at the end of the same century converted to Islam, only a small tribe in Afghanistan now speaks Mongolian (The Mongolian character of their language in 1866 proved G. Gabelents (Ueber die Sprache der Hazaras) on the basis of the dictionary compiled back in 1838 by Lieutenant Leach), the Finnish scientist G. Ramstedt in 1903 saw these people in Kushka, he managed to write down [375] only few words of their language (Ramstedt, Report. From the article is not clear whether Mr. Ramstedt compared his records with the Leach's dictionary. See above, page 211, note 1). To visit these Muslim Mongols in their homeland is not yet possible for political reasons; but probably in Kushka could now be obtained more detailed information about their language and way of life. In the East Asia, in the Kukunor area lives apparently a small people (Tolmukgun) professing Islam and speaking Mongolian. More than twenty years ago an American researcher Rockhill wrote rumors about it, and then this people, as Rockhill was told, had only 300 to 400 families (Rockhill, The Land of the Lamas, p. 44). As is known, the Kukunor area is also of great scientific interest in other ways; it would be highly desirable that future scientific expeditions to that area drew attention to the Tolmukgus. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||